John Hammond: “None of these attractions are ready yet, of course, but the park will open with the basic tour that you’re about to take, and then other rides will come online six to twelve months after that. Absolutely spectacular designs. Spared no expense.”

Donald Gennaro: “And we can charge anything we want. Two thousand a day, ten thousand a day, and people will pay it. And then there’s the merchandising which I personally…”

John Hammond: “Donald, Donald. This park was not built to care only for the super-rich. Everyone in the world has the right to enjoy these animals.”

Donald Gennaro: “Sure. They will. I mean, we’ll have a coupon day or something.”

Ian Malcolm: “Gee, the lack of humility before nature that’s being displayed here, uh, staggers me.”

Donald Gennaro: “Thank you, Dr. Malcolm, but I think things are a little bit different than both you and I have feared.”

Ian Malcolm: “Yeah, I know. They’re, uh, a lot worse.”

Donald Gennaro: “Now, wait a second now. We haven’t even seen the park yet. There’s no reason…”

John Hammond: “Donald, Donald, let him talk. There’s no reason… I want to hear every viewpoint. I really do.”

Ian Malcolm: “Yeah, uh, don’t you see the danger, John, uh, inherent in what you’re doing here? Genetic power’s the most awesome force this planet’s ever seen, but you wield it like a kid who’s found his dad’s gun.”

Donald Gennaro: “It’s hardly appropriate to start hurling accusations…”

Ian Malcolm: “If I may, if I may. Uh, I’ll tell you the problem with the scientific power that you’re, that you’re using here. It didn’t require any discipline to attain it. You know, you read what others had done, and you, and you took the next step. You didn’t earn the knowledge for yourselves, so you don’t take any responsibility… for it. You stand on the shoulders of geniuses, uh, to accomplish something as fast as you could, and before you even knew it, you had, you’ve patented it, and packaged it, and slapped it on a plastic lunch box, and now you’re selling it, you wanna sell it, well.”

John Hammond: “I don’t think you’re giving us our due credit. Our scientists have done things which nobody has ever done before.”

Ian Malcolm: “Yeah, yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied over whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

John Hammond: “Condors. Condors are on the verge of extinction.”

Ian Malcolm: “No,…”

John Hammond: “No, no! If I was to create a flock of condors on this island, you wouldn’t have anything to say.”

Ian Malcolm: “No, no, listen, this isn’t some species that was obliterated by deforestation or, uh, the building of a dam. Dinosaurs, uh, had their shot, and nature selected them for extinction.”

John Hammond: “I simply don’t understand this kind of Luddite attitude, especially from a scientist! I mean, how can we stand in the light of discovery and not act?”

Ian Malcolm: “Oh, what’s so great about discovery? It’s a violent, penetrative act that scars what it explores. What you call discovery, I call the rape of the natural world.”

Ellie Sattler: “Well, the question is, how can you know anything about an extinct ecosystem? And therefore, how could you ever assume that you can control it? You have plants in this building that are poisonous. You picked them because they look good. But these are aggressive living things that have no idea what century they’re in and they will defend themselves. Violently, if necessary.”

John Hammond: “Dr. Grant, if there’s one person here who can appreciate what I’m trying to do…”

Alan Grant: “The world has just changed so radically, and we’re all running to catch up. I don’t want to jump to any conclusions but look: dinosaurs and man, two species separated by sixty-five million years of evolution, have just been suddenly thrown back into the mix together. How can we possibly have the slightest idea what to expect?”

John Hammond: “I don’t believe it! I don’t believe it! You’re meant to come down here and defend me against these characters and the only one I’ve got on my side is the blood-sucking lawyer!”

Donald Gennaro: “Thank you.”

Hopefully you recognized that as a portion from the script of the 1993 Steven Spielberg movie Jurassic Park, based on a 1990 Michael Crichton book of the same name. This scene explores the themes that this article will explore today, themes that have proven prescient since the movie’s release. Welcome to Jurassic Park.

I don’t think it’s particularly surprising for followers of this blog that I am interested in the topic of extinction, as I’ve already written on the extinction of the thylacine, the death of the North American Pleistocene megafauna, and extraterrestrial impactors including a long treatment of the K-Pg impact event. But recent developments in the niche field of de-extinction, taking organisms which have gone extinct and attempting to undo that in some way, has come back into the fore. Projects like these have been going on for about a hundred years. Attempts have been made. A few have arguably succeeded and a few have probably not. However, each time it makes the news cycle, it feels like public amnesia takes hold and the concept is presented as novel again, usually in the interest of promoting a promised world-changing project. This is my attempt to address that lack of a proper historical article on the matter. We are going to go through the whole story of de-extinction from its beginnings to today. Whatever you came here expecting, I am sure you will find something to be surprised about, something to find incredible, and something to be deeply disturbed about.

At its core this is a story about biology. It is a story about what constitutes good science and what doesn’t. It is a story about the ethics of science. It is a story about media and entertainment. It is a story about the human condition and the anxieties of our existence. It is a story about politics and conservation and climate change and genocide and hope. No matter how sterilized the technical discussions of scientific procedures become, and we will discuss those procedures, the actual story of de-extinction and its place in our world is one that needs to be given the context of history to be chewed properly.

We open with the First World War.

Two Brothers and Two World Wars

World War I produced extensive aerial landscape photography that was used for reconnaissance in military operations, preserving our knowledge of how the war affected landscapes. This photo is from the Battle of the Somme in northern France, which lasted for more than 4 months in 1916 and involved more than 3 million soldiers over its course. Photography by the No. 10 Squadron of the British Royal Flying Corps, which became the Royal Air Force after the war. A portion of the British trenches are shown in the upper picture and the German trenches in the lower.

On June 28, 1914, a Serbian nationalist by the name of Gavrilo Princip fired a shot in the streets of Belgrade, a city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and today in Bosnia and Herzegovina), that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Austria-Hungary threatened annexation of what remained of independent Serbia, which called on the Russian Empire for defense. As Russia loomed against Austria-Hungary, the German Empire declared itself in support of the latter, to which France and Britain took notice and issue. A diplomatic crisis spiraled out of control and soon Europe was at war in what we remember as World War I, lasting from 1914 to 1918, eventually drawing in outside powers like Japan and the United States and being waged on many continents. The human death toll of World War I was immense and varies depending on what you count as part of the war. The war killed around 15 to 22 million people, but the general period of history was even bloodier as it led directly into other conflicts such as the Russian Civil War of 1917 to 1922 which killed around 7 to 12 million people and it overlapped with the 1918 to 1920 global influenza pandemic which killed between 25 and 50 million people. These other things aside, part of what made World War I particularly brutal was the innovations made in carrying out industrialized warfare. Innovations in aviation meant the beginnings of aerial bombing campaigns while bigger artillery could lay hell on enemy troops from kilometers away and gas attacks poisoned air and burned the skin and lungs of enemies in terrible and disfiguring ways. The most enduring image of World War I for many people is the trenches, which cut across hundreds of kilometers of especially Europe, fortifying entire landscapes in long stalemated face-offs where soldiers lived and died in squalid pits and the terrible torn-apart no-man’s land that lay between them.

The human impact of the war should not be understated but another side of the conflict that many people today don’t think about is its ecological impact. World War I was incredibly impactful on resource use, land use, and pollution. As vast regions of countryside became battlefields for extended periods of time, local ecosystems were pounded into mud and chemical weapons laid destructive compounds into air and water that had far more victims than only human soldiers. Copper and lead contamination in soil and water spiked to the point where at many times plants could not grow in areas where they grew lushly previously and unexploded mines and other ordinances lay in wait to turn unsuspecting animals into red mist. In northeastern France for example, a large area was designated as Zone Rouge, the red zone, where the land was considered for a time unlivable and crops would not grow, with some towns never coming back after the war. On top of this was the demand for wood, which remained a key necessity in waging war, even in the technological age. Every new trench or every adjustment or repair was essentially a construction job as wooden elements were required to give structure to the interior of the defenses. So even far from the battle lines, combating nations had to cut vast areas of forest fast for delivery to the front. It was this that had a long-term environmental impact on Europe more than the chemical pollution and mines. Weaponized chemicals would eventually be carried away and sequestered by natural processes after the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918 but the ecology of large-scale ecosystems is a little harder to heal in the same way. As Europe’s forests grew back in, formerly diverse environments were often left to a few hardy tree species that colonized them quickly, often not carrying along animal populations that had previously thrived there.

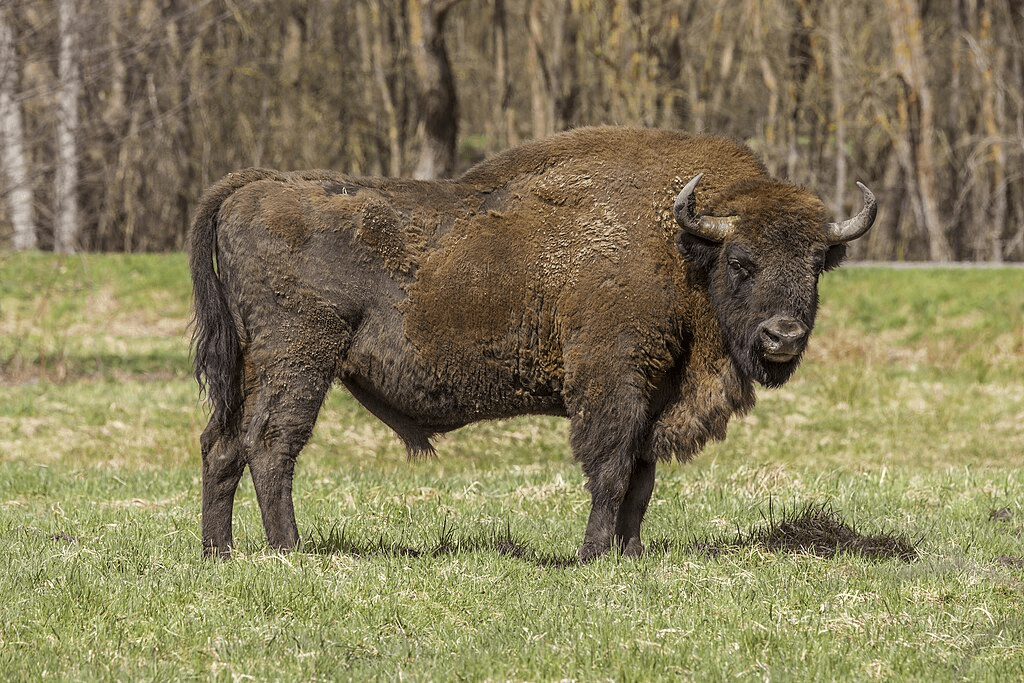

This is a wisent or European bison (Bison bonasus) in the Białowieża Forest in Poland in a picture by wildlife photographer Charles J. Sharp.

The wisent is the European bison (Bison bonasus), part of the same genus as the American bison (Bison bison) that is a little more famous. Today they are the heaviest native land animals of Europe and were once common in the Pleistocene (probably spreading to Europe around 100,000 years ago from the steppes to the east), depicted in cave paintings by the prehistoric people who lived there. The last few thousand years have been hard on them as civilization encroached on their habitat and they became a rare prestige animal to hunt for use in the making of fine clothes and drinking horns and as the centerpiece of a feast. They were already an endangered species when World War I happened but during the war their habitat was destroyed and German soldiers hunted many of the last ones in a region of what is now Poland. In 1927, the last wild one was shot in the Caucasus, leaving 48 alive in the world’s zoos. This issue became of interest to a pair of German brothers by the names of Heinz and Lutz Heck. The Heck brothers were the son of the director of the Berlin Zoo and had grown up surrounded by animal breeding, starting with rabbits when they were very young. Their father had made use of the German Empire’s colonial holdings in Africa and elsewhere (all lost in the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the war) to bring in new animals as specimens to one of the world’s foremost research zoos. Naturally, the two boys made their way into science as adults quite nicely. Conservation as a movement had been growing in popularity in recent decades and in the case of the American bison (many of which were destroyed in the 1800s purposefully by US settlers to try to harm Native Americans who relied on them by proxy), efforts to protect them starting in 1905 had seen some success, inspiring conservationists in Germany to start thinking about doing the same for the far more critically endangered wisent. Heinz Heck laid the groundwork for a breeding program by beginning to take notes on every living wisent in captivity in 1923, which would become a published work in 1932, the first work of its kind for a non-domesticated species. Using this book, zoos could coordinate wisent breeding, which helped to increase the numbers of the animals. Thanks to him and others who worked with him, the wisent is not extinct today. Lutz Heck thought about fortifying the wisent breeding pool through crossbreeding with the American bison as well. Heinz recognized what scientists today still believe: the decline of the wisent, like that of many other species, related to it being hunted and pushed out of its habitat for thousands of years and it began in prehistoric times and was seeing its apex in industrial civilization. It would be nice to say that the brothers’ efforts led to wild wisent populations in their lifetimes but the reality was that another war was about to strike the European biosphere and that the wisents that roam wild in Europe today actually result from the continuation of the captive programs after said war. And one of these brothers would play a small but tangible role in the unfortunate social atmosphere that led to this war.

This set concept, photographed by Austrian photographer Viktor Angerer, was developed for the 1876 showing of Das Rheingold, the first of four operas in Richard Wagner’s epic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which presented a series of adapted Norse myths in epic Romantic fashion. Wagner was not a Nazi by any means and died in 1883 long before he could get mixed up with that bag of shit, but his impact on how Germans romanticized their past was immense and informed a lot of later Nazi völkisch fantasy. Hitler was a particularly big fan of Wagner and sometimes forced the Reich’s higher-ups to attend showings, which they did not all appreciate.

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party, or Nazi Party for short, was founded in 1920, just two years after the end of World War I. Despite the socialist moniker, its constituents were extremely far to the political right and the party would spend its early history shifting from being anti-capitalist towards courting the interests of business. From 1921 onwards, the party fell under the leadership of one Adolf Hitler, a veteran of the Great War who considered the Treaty of Versailles deeply unfair and insulting to the German people and blamed a supposed international cabal of Jews and communists for conspiring against a German “Aryan” master race. At the time, German nationalism increasingly appealed to “völkisch” (in English, something like “folkish”) narratives which appealed to an idealized German past. Romantic adaptations of old Norse myths and pseudoarchaeology were used to imagine an age of heroes when ethnically “pure” Germanic Aryan figures laid the foundations for civilization in a pristine landscape, free of all those that German-supremacists considered undesirable, groups which included Jews, Romani, Slavs, the disabled, homosexuals, and black people. Such a world never truly existed but in the early 1900s it was nevertheless impacted by current understandings in archaeology, linguistics, and human origins and ideas from those areas of inquiry were twisted to fit the völkisch vision. Hitler and the Nazis excitedly embraced this storytelling and promoted them as patriotism in society. From 1929 onwards, the economic downturn known as the Great Depression hit Germany’s Weimar Republic especially hard and the Nazi message increasingly appealed to Germans who saw them as offering some form of change. The rise of the far-right split German society… but that is of course how fascists operate.

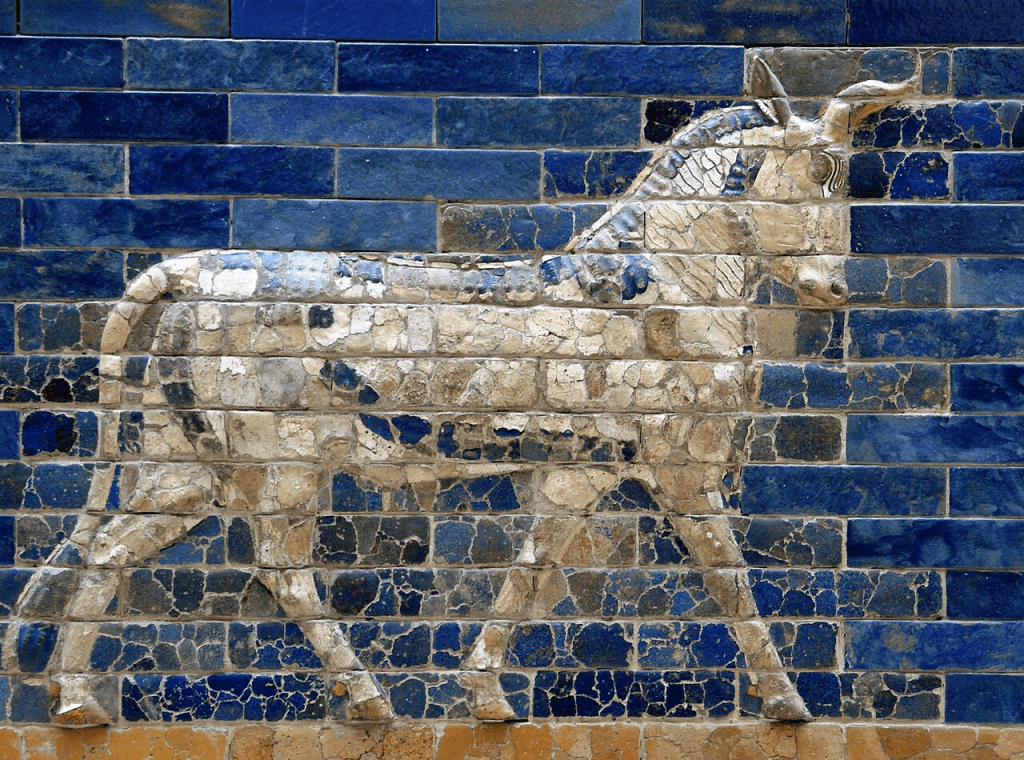

O, sorry, you had to read about the rise of Hitler in what you thought was an article about animals? You’ll make it; unfortunately it’s relevant. Back to animals for a bit. This is a depiction of an aurochs (Bos primigenius) from the Ishtar Gate of Babylon, constructed in the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II around 569 BC. The aurochs was a known animal in the Iron Age Near East, referred to in both the Bible and in Mesopotamian texts, where it was a prestigious animal to hunt for kings and others looking to display their strength. Photo by Josep Renalias.

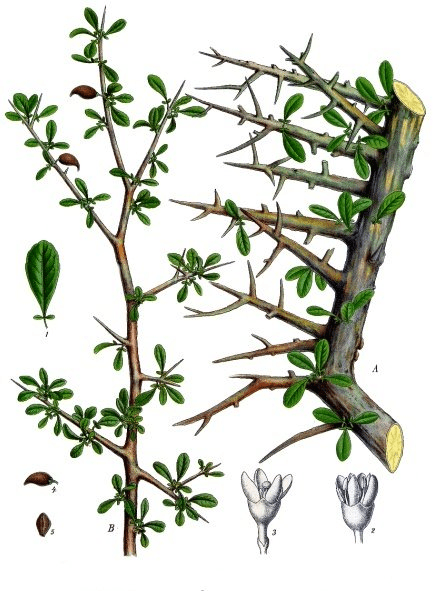

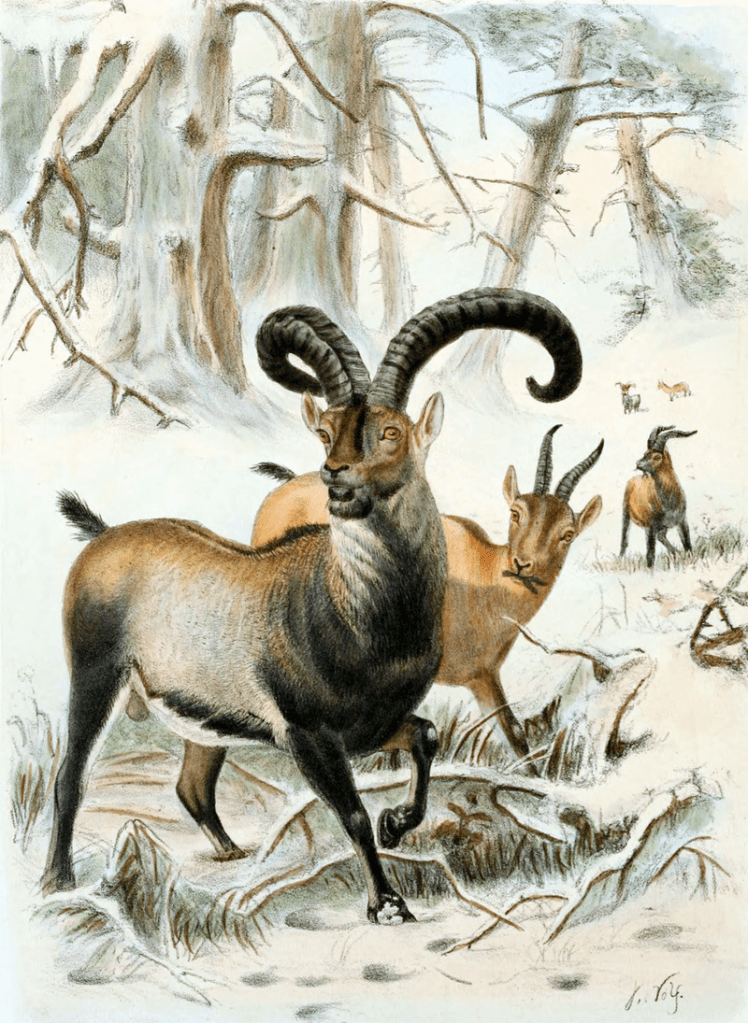

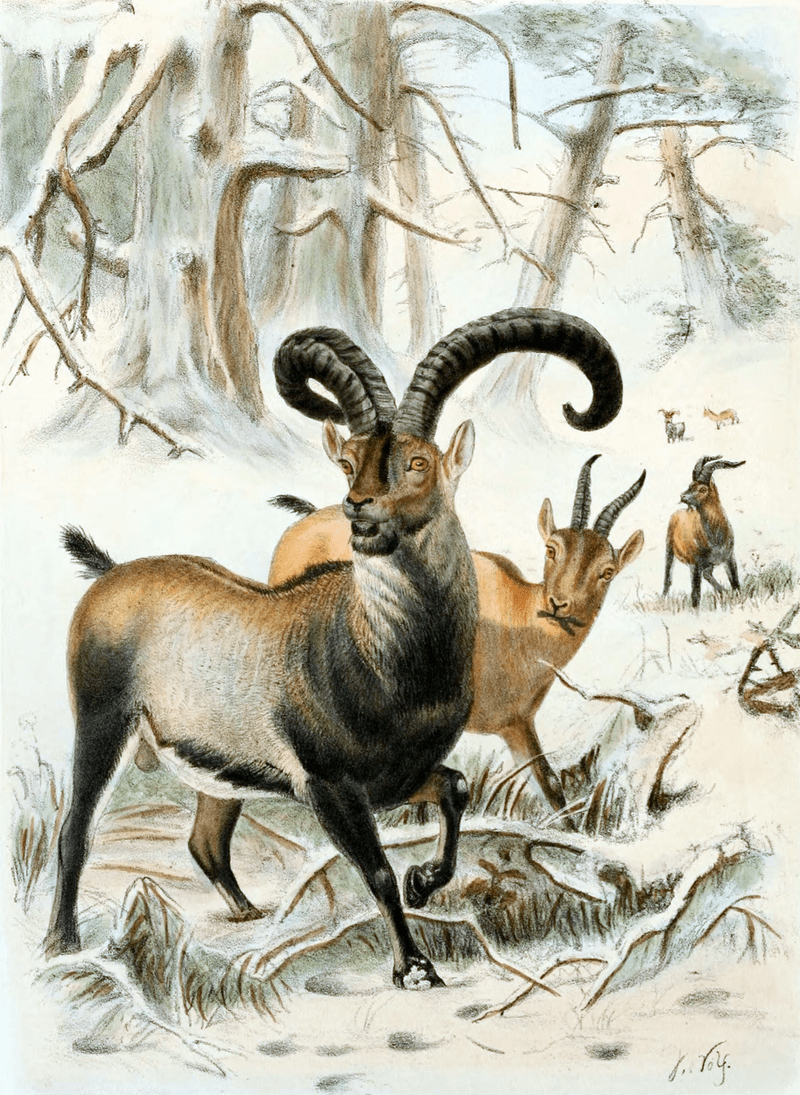

While all this was going on, the Heck brothers were seeing success with the wisent program and began to think about other animals that could be the subject of breeding programs and used to restore Europe’s former wildlife. They took interest in the aurochs (Bos primigenius), but unlike the wisent which had only gone extinct in the wild, the aurochs was extinct altogether. These large wild bovines could have a shoulder height of up to 1.8 meters tall and were extremely widely distributed across Eurasia and North Africa in the Pleistocene, hunted by both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, with ritual use of their bones by the former and painted depictions by the latter. As the ice retreated and climates changed, so too were there changes in how humans interacted with the aurochs. Two separate species of cattle were actually domesticated from the aurochs: Bos taurus (which most readers probably think of if I say the word “cow” or “bull”) starting from around 8,800 BC in the Fertile Crescent and Bos indicus (the zebu) starting around a millennium and a half later in the Indus Valley. As the Neolithic transition gave way to urban civilization, domesticated bovines became far more numerous than the wild cousins they split off from, but they were also a lot smaller. As such, the giant wild untamed aurochs became a rather prestigious animal for the upper classes to hunt in many civilizations from the kings of Mesopotamia to the heroes of Greece, who fashioned their horns into drinking vessels. But by the early modern period, habitat loss, hunting, and competition with their domesticated cousins had pushed the aurochs into just a few small territorial holdouts and the last known one died in 1627 in what is now Poland. The Heck brothers were aware that modern cattle had been bred from the aurochs and so invented method number 1 in the history of de-extinction: back-breeding. Back-breeding is taking the descendant species of an extinct one, such as a domesticated animal developed from a wild animal, and selectively breeding it for traits deemed ancestral.

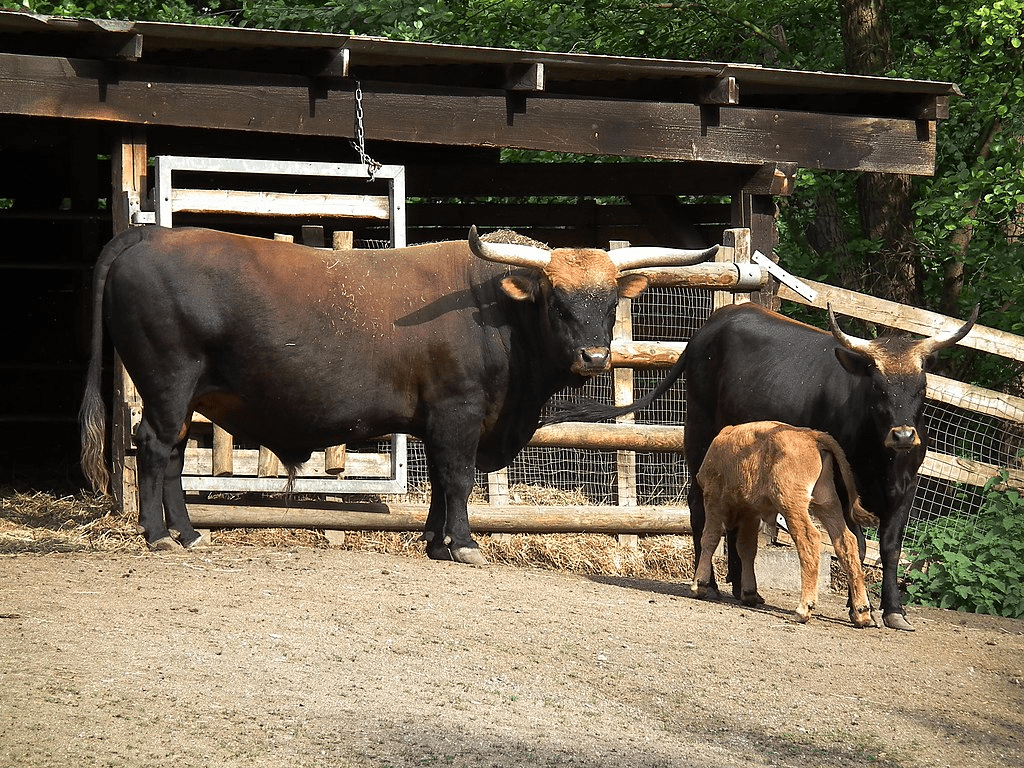

Heck cattle, a breed of cattle created as a result of the Heck brothers’ efforts to back-breed the aurochs from domesticated cattle (Bos taurus). Photo by Wikimedia contributor 4028mdk09.

Heinz became head of the Munich Zoo in 1928 while Lutz inherited the Berlin Zoo with the passing of their father in 1932. They each began their breeding programs separately and while many of their original notes have since been lost, we do know they were informed by many sources such as history, archaeology, and mythology in producing their cattle, which I will call Heck cattle here, since that is the name they are called by today, though the brothers would have considered the results de-extincted aurochs. Lutz in particular, an avid enjoyer of hunting, associated the aurochs with a fighting spirit and specifically gave his cattle a streak of Spanish fighting bull. In the background, as the project was getting off the ground, one Adolf Hitler was made chancellor of Germany by the president Paul von Hindenburg in early 1933, shortly before a fire destroyed the Reichstag, the German parliament building, giving Hitler the pretense to give himself emergency powers and purge the government of leftists and other critics. The project had begun in the waning years of the Weimar Republic but it was now in the new order of Nazi Germany that the brothers declared their success. At the same time, they also bred horses to resemble the tarpan, the wild ancestor of the domesticated horse (Equus ferus, both the wild and domesticated varieties here are considered part of the same species), creating a breed known as Heck horses.

Nazi Germany was a fully totalitarian regime which sought to model every facet of society under it to fit its violent idealistic vision. It was a dangerous place to be an intellectual where ideology was required to operate along state lines and academics who didn’t play along could be dismissed or worse. Heinz was not liked by the new order. He was quiet about it but he does not seem to have agreed with the Nazi ideology of natural purity and he was arrested by the regime, which cited his previous brief marriage to a Jewish woman (considered race treason within the ludicrously antisemitic segregationist ideology of Nazi Germany) and suspicions that he was part of the now-illegal Communist Party (which doesn’t seem to have been true). He was one of the first people interned at the concentration camp of Dachau in southern Germany, which originally housed political dissidents but would eventually grow to become a major forced-labor camp where Jews and other persecuted peoples would work and die and in some cases be medically experimented upon. Heinz got off lighter than most of these later prisoners and was released shortly, but it was pretty clear that he would never rise that high in Nazi Germany. Other than a history of the aurochs he wrote in the 1940s, he faded somewhat into the background. Lutz, meanwhile, ate the forbidden fruit.

If you are familiar with the political history of the Third Reich, then you naturally recognize the name of Hermann Göring as one of its major figures. Göring had been a flying ace during World War I and after the war became one of the earliest members of the Nazi Party, cozying up to Hitler through his entire rise into political prominence. Following the takeover of the government, he had been given a vague and flexible ministerial position that took on a variety of different unrelated roles, overseeing many of Hitler’s early reforms. Most notably, though, he became chief of the Luftwaffe, the German air force, in 1935, and it was widely understood that he was a designated successor, should anything happen to Hitler. Göring was effectively the second most powerful figure in the Reich aside from Hitler and, luckily for Lutz Heck, he was very into hunting and had secured political authority over managing hunting and forests amidst everything else. Lutz and Göring managed to become hunting partners and soon after Lutz increasingly operated on behalf of party aims, such as his trip to Canada to acquire animals in 1935 where he also spoke publicly to promote national socialism. In 1938, Lutz Heck wound up as head of the Nature Protection Authority, essentially the Nazi conservation minister. On September 1, 1939, World War II began in Europe as Germany invaded Poland, which had become independent after World War I and which Nazi propaganda emphasized taking back, prompting Britain and France to declare war on the Reich to curb Germany’s aggressive repeated expansionism.

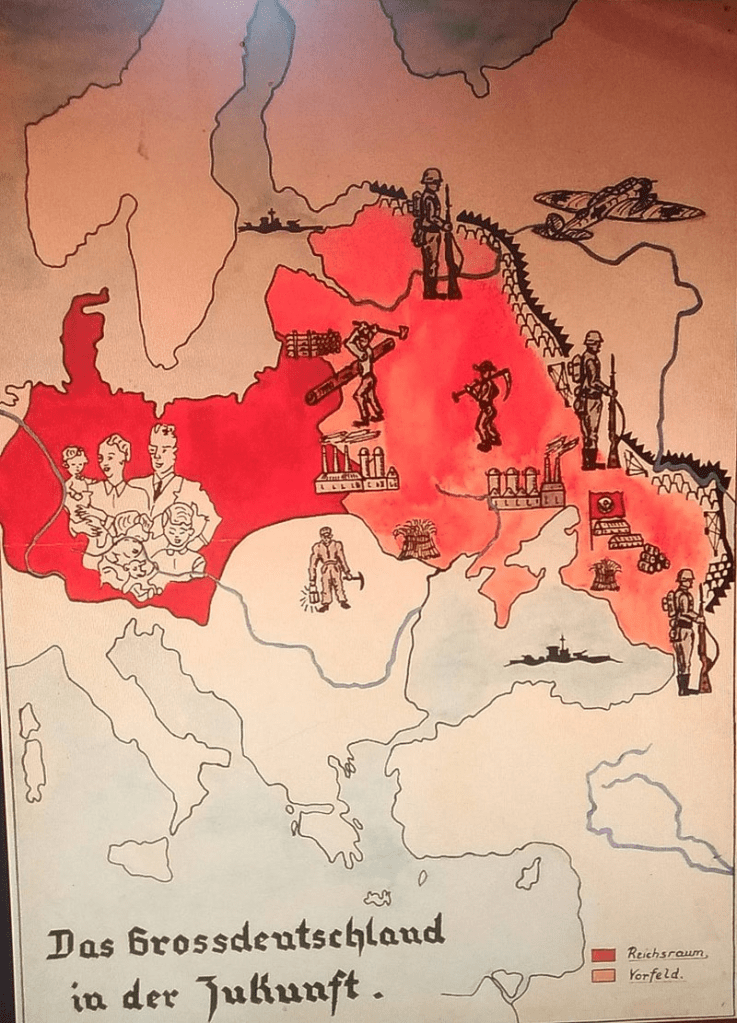

“Greater Germany in the future.” This Nazi propaganda map from 1943 shows an imagined fulfilled Generalplan Ost in which a German-settled east (from which all other peoples would be killed, enslaved, or removed) produced food and industrial goods for Germans to live prosperously back home. At the time this poster was made, all of that land was German-occupied but within the next two years the USSR would drive the Nazi war machine back all the way to Berlin. Image put on Wikimedia by PraetorXXXfenix but the original artist was some Nazi fuck whom history has forgotten.

That year German authorities began to produce what would be called the Generalplan Ost or GPO, the master plan for the east, a genocidal plan to remake Eastern Europe demographically and environmentally. Despite its formal sound, the GPO was in constant flux for the remaining history of the Reich, but it is possible to summarize its general goals. Hitler had made a major ideological goal in Lebensraum, living space, which referred to the idea that the German people must increase the territory in which they were able to propagate. Within the purist racial mindset of Nazism, this meant clearing that land of whatever other people groups had been there through extermination, enslavement, and expulsion. The GPO proposed that the lands to the east of Germany in what had previously been Poland and the Soviet Union would be the primary subject to this expansion project. Major cities like Warsaw would be removed from the map and replaced with entirely German colonial settlements, which were described in terms that appealed to a primeval romantic rural fantasy, and bountiful harvests would feed a German population boom there and back home. The Nazis generally thought of this as a postwar plan that would follow final victory, especially against the Soviet Union, which they invaded in 1941 to begin to make it possible, adding yet another front to their world war, which had already made them masters of continental Europe… for the time being. And in case you forgot that you’re reading an article section devoted to bison, cattle, and horses, this is what Lutz Heck was needed for: preparing the animals that would populate the landscape of a fulfilled Generalplan Ost, animals which Göring and Lutz associated with a primeval Aryan-ruled landscape of long ago. That and Göring liked hunting and actively filled his private forest in Poland with all these animals. All of this to service the same large-scale project that was also being invoked as millions of people were being rounded up and sent to death camps. As an observation that many sources have made on this issue as well, there is something to be said here about the relationship between breeding an idealized purified species and the eugenics which the Nazis practiced.

We know in hindsight that the final victory envisioned by the Nazis never happened thankfully. Lutz Heck’s access to support was very much tied to that of Hermann Göring, which relied on the opinion of Adolf Hitler, whose pleasure with Göring decreased after 1941. As commander of the Luftwaffe, Göring had been the first person Hitler went to on the matter of both launching aerial attacks and defending against them, but after the heroic defense of the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain in 1940 which destroyed the Reich’s plans to invade the UK, the commencement of heightened British (and now American) bombing campaigns against German cities in 1942, and the ongoing failure of the Luftwaffe to properly support the Germans’ slowing advance in the war with the Soviet Union, it was hard for him to look good. Amidst all this, Göring was increasingly spending time in his luxurious private estate full of exotic “de-extincted” huntable animals and expensive goods taken from the collections confiscated as part of the literal Holocaust. In 1943, the Soviet tide turned and the Red Army began driving the Germans westward. The next year, American, British, Canadian, French, and other forces landed on the beaches of Normandy to begin the liberation of France and then push east. Nazi propaganda was unrelenting though. It was, so it said, the German destiny that they would still win and create their final plans, no matter the present difficulties. These delusions were actively costing both the lives of innocents and of German manpower. In terms of nature preservation, the hypothetical job of Lutz Heck and the thing the brothers had first wanted to work on after World War I, it was hard to say that the wars being waged by the regime Lutz now was part of were anything but intensely destructive once again to the biosphere of Europe. There were more important things to keep track of, but for the record the wisent was not doing well.

If you have heard of Lutz Heck before this, it may be in the context of the Warsaw Zoo. When the Germans took over Poland, the zoo was managed by Jan and Antonina Żabiński and sometime later Lutz was tasked with pillaging the zoo of what he considered “valuable” animals, one of many examples of the German occupation taking what it pleased from occupied lands. But unbeknownst to him, these two zookeepers would be remembered more positively after the war for what they did in secret. Jan kept his post and was approved as a park manager under the occupation, which gave him the clearance he needed to enter the Warsaw Ghetto, where Jews had been forced to live sectioned off from wider society. Using connections and the holding space that came with a partly pillaged zoo, the Żabińskis would take some 300 Jews through the zoo to escape the horrors of the Holocaust. In 1944, the people of Warsaw knew that the Soviets were coming, but following the previous Soviet invasion of their country in 1939 (several weeks after the Germans, splitting the country), they knew that Soviet dominion would simply mean rule by a different foreign autocracy. So the Poles revolted against the Nazis on their own terms in the heroic Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which unfortunately failed, leading the Germans to senselessly level the entire city. Jan was arrested in this rebellion but Antonina continued her work in his absence, aiding people to freedom. After the war, they helped build the zoo up again. I bring this story up not because of its relation to de-extinction, but because I think it’s important to see that people with similar positions in the world to the Heck brothers responded to the Nazi situation differently than they did. I think it’s important to keep this in mind. Important to Lutz Heck and Hermann Göring, however, was the latter’s private estate in the Białowieża Forest. As the Red Army saw such an important location as a target, it fell under orders to be captured and in the process most of the large animals there were killed, including the wisents and the “de-extincted” cattle and horses.

1945 was the year of judgement for the Third Reich. On April 16 of that year, the Soviet Red Army began to attack Berlin and the forces of the United States, Britain, France, and others were flooding into western Germany. Death camps were being liberated and German forces were deserting, being captured, or getting destroyed. Hitler ordered fights to the end and even the Hitler Youth were being pressed into service, all while the dictator himself hid in the Führerbunker. On April 22 as the city was actively being invaded, Hitler sent a message to Göring and other top officials informing them of his intention to commit suicide instead of being captured and humiliated. Göring asked if he could assume control of the government in his stead but was told that this constituted an act of insubordination and he was arrested. On April 30, the führer put a gun in his mouth and blew his brains out, doing a rare service to the world. In the opening days of May, it was clear which way the battle was going to even extremely ideologically driven Nazis and many of them started to recognize that they would need to surrender to someone and the Soviets weren’t the most easygoing captors, prompting a lot of Nazi officials to move west to surrender to the nearby Americans. This included both Hermann Göring, who had escaped his holding place, and Lutz Heck, who made his way to Bavaria and whose animals were mostly killed in the battle. The war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945. Göring was sentenced to death for crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946 but he killed himself by cyanide pill the night before his scheduled hanging. All theaters included, World War II was the deadliest conflict in human history, totaling some 70 to 85 million deaths. Maybe it is not surprising that the history of de-extinction is so tied up with this war, because so is almost everything else in the human history that has followed.

Heck cattle collage by Wikimedia contributor DFoidl.

Lutz Heck got off alright, except he lost his post at the zoo in Berlin and his animals had been largely destroyed. But Heinz Heck, on the other hand, always further from the center of the Reich that the great powers of the world had so righteously destroyed, had his collections at the zoo in Munich, which, despite taking damage in the war, was still able to recover enough to reopen the very month that the war in Europe ended. Heck cattle today have been distributed to many parts of Europe and they have some distinctive traits, such as their very pronounced horns and their climatic resilience. Because the Heck brothers had promoted them as the aurochs returned, they became popular to pick up in zoos in Germany. But with the end of the war and the detachment of the narratives about these cattle from those of the old regime, it became extremely apparent that they remain very distinct from the still-extinct aurochs. Breeding for the aurochs’s appearance had essentially been eyeballing it, especially as the structure of DNA was not even understood at that point, meaning the Heck brothers had no way to compare the genetics of the cattle with their extinct ancestors’. Heck cattle are no larger than most domestic cattle and are certainly smaller than the typical aurochs. Nevertheless, it seems that they have a very important place in conservation today. Modern Europe is largely devoid of large grazing animals, which normally play an important part in grassland ecosystems where they regulate invasive species and aid in nutrient recycling (through their nitrogen-rich shit and yummy corpses) and so help these environments to be more stable. In the 1980s, a Dutch polder (an area of land created by artificially holding back water using dikes and seawalls, common in the Netherlands) by the name of Oostvaardersplassen became the 56-square-kilometer center of an ecological experiment: to try to stabilize a newly made grassland through the introduction of grazers such as deer, ponies, and notably Heck cattle. Around 600 of the cattle roam free and wild here and seem to be doing largely alright. The aurochs has not returned, but something novel has been made and maybe, as Europe addresses its tragic ecological history, the true likeness of the Heck cattle to the aurochs will be found in the ecological niche they will play. Detached from ancient Aryan fantasies of course.

Muted Stripes

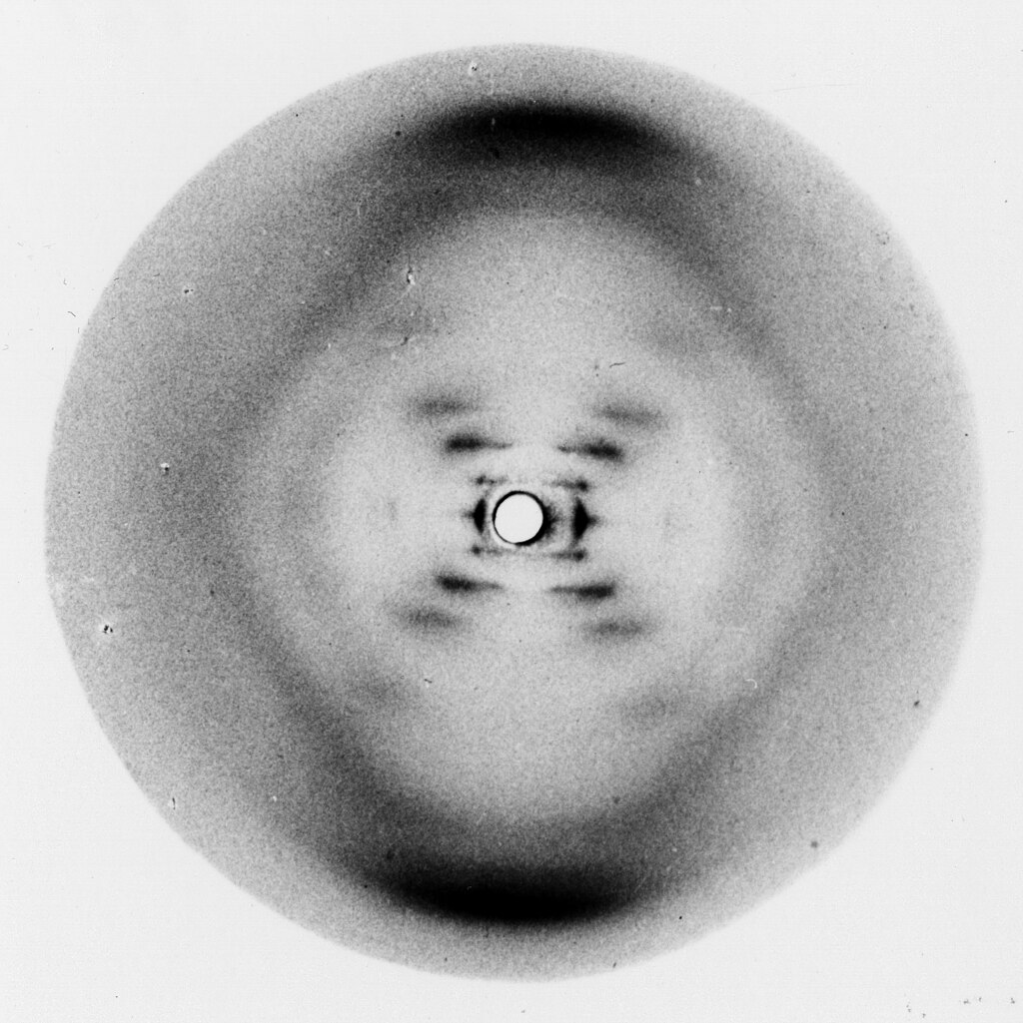

The famous “Photo 51,” taken by Raymond Gosling under the direction of Rosalind Franklin in 1952 using an x-ray diffraction process on DNA. This photo was key to the reconstruction of its structure.

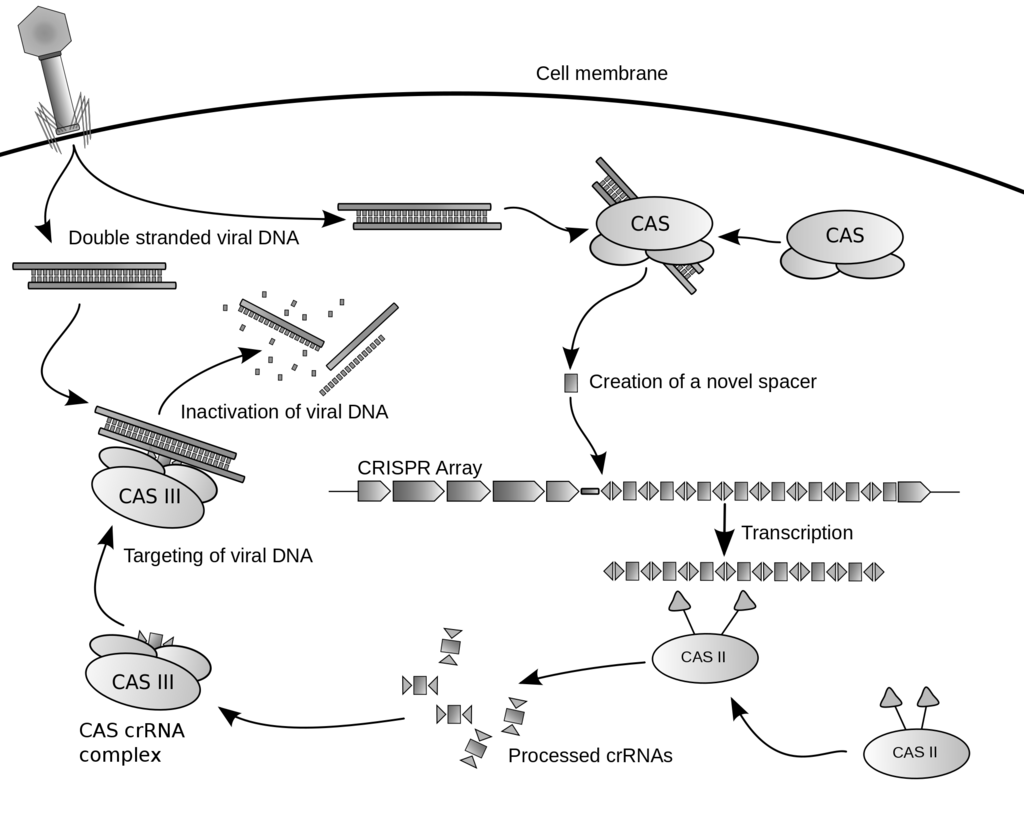

What separates, on a scientific level, the early attempts of the Heck brothers from many more modern projects to bring back extinct organisms is the knowledge of the structure of DNA. Genetics as a scientific theory is actually rather old, originating with Austrian abbot Gregor Mendel experimenting with the heritability of traits among pea plants, identifying dominant and recessive traits and publishing his statistical findings in 1866, though they would largely go unnoticed until rediscovery and reconfirmation in 1900. In a completely separate development in 1869, Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher was able to isolate and identify a substance from the nuclei of cells suspended in the pus left in discarded surgical bandages, calling it “nuclein,” which we now recognize as largely DNA. For decades, researchers would pick this material apart, gradually identifying components until in 1928 the British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith observed that different strains of pneumococcus bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae) could pass traits between each other through material interaction, something that a Canadian and American research team would confirm was DNA in 1943. So the medium of Mendel’s inheritance patterns was this chemical but how information was encoded into it remained a question. The breakthrough came in 1952 when a student working in the lab of British chemist Rosalind Franklin used X-ray diffraction to take an image of DNA which was then shown to American geneticist James Watson and British molecular biologist Francis Crick. The latter two presented, based largely on the image as well as other information, a double-helical structure of the DNA molecule (though it’s important to note here that Franklin herself seems to have done much of this work as well and was given minimized credit at the time). This revolutionized understandings and further advanced conceptions of the genome. But this did not revolutionize de-extinction overnight because the technology to sequence and edit genes was still coming. Keep this bit of background in your mind for later. Let’s talk zebras.

Zebras are actually a few different species in genus Equus, which you Latin students can already guess includes horses. The genus has seven living species, which are grouped using the rare taxonomic category of subgenus between genus and species, based on coming from speciation events in little groups. In subgenus Equus we have Equus ferus, which is both the wild and domestic horse. In subgenus Asinus we have the donkeys of Equus africanus (ass), Equus hemionus (onager), and Equus kiang (kiang). In subgenus Hippotigris (yes, horse-tiger; it’s excellent) we have the zebras of Equus grevyi (Grévy’s zebra), Equus quagga (plains zebra), and Equus zebra (mountain zebra). Today our interest lies with the plains zebra or formerly Equus burchellii, which as of my time of writing this is still how it’s labeled at the Parc Zoologique de Paris where I was the other day. (Update your signs.) The reason for the change, which occurred only in the last couple decades is that an extinct variety of zebra known as the quagga was found via genetic analysis to be a subspecies within the same species. Since the quagga was technically described by science first, its scientific name became the winner of the merge in accordance with the taxonomic principle of priority where older scientific names are considered generally more valid. So what were the quaggas?

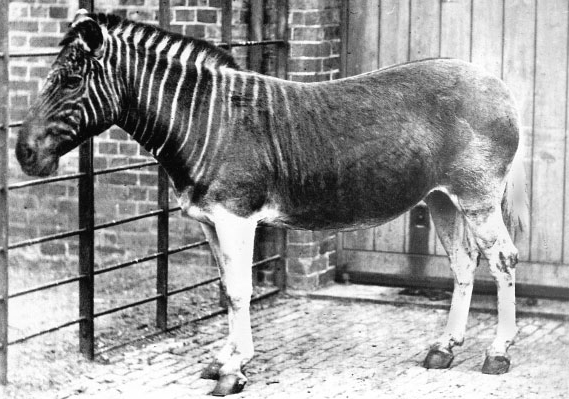

A quagga (Equus quagga quagga) at a zoo in London in 1870 in a photograph taken by one Frederick York.

Quaggas were once a common subspecies of zebra in what is now South Africa. They were easy to identify because they had a relatively unique color pattern of primarily brown with white stripes limited to the front part of the animal and white legs. In 1984, skin from a quagga kept in a museum became the first sample of DNA (specifically mitochondrial in this case) taken and partially sequenced from an extinct animal, representing a giant step in the story we’re telling today. Multiple quagga samples would be taken until by the early 2000s it became more possible to place the quagga within the evolutionary tree, where it became clear that it was a divergent population of plains zebra and that the animals actually had a relatively low genetic diversity, signaling that divergence as recent in grand geologic timescales, as recently as between 290,000 and 120,000 years ago, when our species Homo sapiens was already proliferating through the African continent. Some other African ungulates seem to have gone through a similar period of differentiation around this time and it has been suggested that Late Pleistocene climatic shifts may have caused habitat fragmentation and rearrangement across the continent that drove its regional diversification. Being a recently emerging animal in southern Africa makes the quagga a somewhat interesting case in the history of animals which have gone extinct in the Holocene in that it spent its entire history alongside humans and even thrived in the same environment with them. Quaggas are depicted in Khoisan rock art and the word “quagga” is itself an onomatopoeic word derived from one in the Khoikhoi language emulating the animal’s call, which older anthropologists transcribed as “kwa-ha-ha” and similar. (As a sidenote, a lot of sources you read on this topic, including the website of the Quagga Project itself, use the term “Hottentot” for the Khoikhoi language. This is, to my understanding, widely considered a historical Boer racial slur for this ethnic group which has an unfortunate legacy in South Africa’s racial history. If you decide to dive further into this topic, you should be aware of that.) The quagga was first described in European science in 1778 by Dutch naturalists after that country’s colonization of the Cape region. It became known as a relatively easy animal to hunt and so it was frequently targeted for its skin and meat, especially by Boers, the people descended from Dutch settlers who increasingly settled inland in their own independent republics following Britain’s acquisition of the Dutch Cape Colony in the early 1800s. Quaggas were recognized as more docile than other zebras (which can actually be rather aggressive and territorial animals), often in herds of only between 15 to 30 and accompanied by ostriches and wildebeest. Since horses often died to sleeping sickness in southern Africa, Cape Colony even considered the quagga as a candidate for a domestication project and local farmers often allowed them to be near livestock as they might act aggressively towards predators and keep herds safer. It was fashionable to capture specimens for zoos in Europe, two quaggas in London becoming rather notable for at times pulling a carriage around Hyde Park. But as a prized hunted animal and as a competitor to domesticated grazing animals in certain settled regions, pressures were kept up on the quagga before extinction was even recognized as a looming problem. The last known living individual died in a zoo in Amsterdam on August 12, 1883, though naturalists did not recognize it as the last individual at the time and the zoo even asked for anyone who was willing and wanted a reward to bring them a new one, possibly at least partly due to confusion created by the general use of the word “quagga” in Afrikaans to refer to all zebras.

Reinhold Rau with a quagga foal specimen in a photo from the Quagga Project.

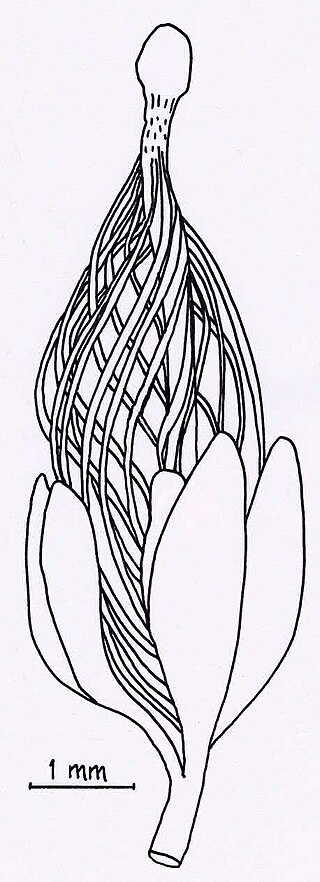

The roots of the idea of bringing back the quagga actually go back to Lutz Heck himself who suggested in 1955 that breeding programs similar to his experiments in cattle and horses might work to produce a plains zebra with a similar pattern to the quagga, but this was after the height of his particular influence and he would never oversee this project. This is where naturalist Reinhold Rau entered the picture, after having been inspired by a quagga foal specimen at the South African Museum in Cape Town in 1969. In 1971, he went on a European museum tour to investigate quagga specimens and hatched a plan to try to revive them through selective breeding of the plains zebra that focused on a brown color and reduced stripes. Initial attempts to propose the idea to various parks in South Africa, Namibia, and Swaziland were met with disapproval but Rau remained interested and was contacted by a veterinarian by the name of J.F. Warning, who had been an old friend of Lutz Heck, in 1985, one year after the first quagga DNA samples had been published, interested in carrying out the project, which they finally started in 1987. The Quagga Project began with the capture of nine zebras from Etosha National Park which were then taken to a farm known as Vrolijkheid near the town of Robertson in the Cape. Within the next several years, the first foals were born to the project, which began importing a larger number of zebras, reaching 83 by 2004, when the project had 11 locations. Feeding a large number of zebras proved a financial issue for the private project and so gradually expansion has focused on allowing more of the zebras to do natural grazing. Some foals have also been sold off.

Some of the selectively bred zebras of the Quagga Project in a photo by Wikimedia contributor Ogmus.

In its nearly four decades of operation, the Quagga Project has achieved a general success at breeding brownish zebras with reduced stripes and their website keeps a studbook of individuals which shows its efficacy very well. Rau passed away in 2006 but the project continues after him, having bred the animals now across more than five generations, whittling down a large genetic pool into a more focused one which emphasizes traits associated with the quagga. Since the quagga is considered a subspecies of the plains zebra, the project is generally considered more viable than some other de-extinction concepts that focus on entire extinct species and the website of the project even endorses the idea that extinct species cannot be truly revived. The website presents the extinction of the quagga as a “tragic mistake made over a hundred years ago through greed and short sightedness” and therefore as something which it can rectify. It continues a tradition of the concept of de-extinction being tied to conservation. The animals are not exactly contiguous with the populations historically known as quaggas and so biologists are unlikely to recognize them as identical, so the title of “Rau quaggas” has been proposed for the new animals. I wish these newcomers well.

Life… uh… Finds a Way

(This section contains major spoilers for the Jurassic Park novels and books. They are a rather important part of telling our story.)

The original cover of the novel. This book is really good.

American science-fiction author Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel Jurassic Park references efforts regarding the quagga very briefly, where its DNA extraction in 1985 is part of what gets InGen, the powerful central corporation in the story, interested in the idea of resurrecting dinosaurs. Reading between the lines, it’s not hard to get the idea that this development had some part in inspiring Crichton as an author, though he was apparently working with the idea in some capacity as early as 1981, but writing the put-together version began in 1988. It published after two years of redrafting, with early readers not liking early drafts. The final version though was a well-received masterpiece. In the next paragraph, I will spoil some things.

Jurassic Park opens with a prologue that reflects on the rapid pace of scientific progress in the modern world, specifically in the field of genetics, which is compared to other revolutionary technological advances such as atomic theory and computing. The central themes of the movie are set up with the idea that science, which was once open and about discovery, was increasingly being taken up by private companies that did things in secret, to try to be the first, and for profit. In the novel, the corporation InGen, which is run by a shady and eccentric businessman named John Hammond, attempts to secretively set up a specialized theme park on a remote jungle island off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica, which is effectively unregulated by any country. Investors are skeptical as the park largely does not tell many of them exactly what it is, which sets up the central conflict as several horrible workplace deaths at the location harm goodwill and so Hammond seeks out a number of specialists to tour the park and give their expert approval. It turns out that what InGen does is take the genetic material of dinosaurs out of their fossils and out of the stomachs of insects that have drank their blood and become trapped in amber. (This is a science-fiction device as the preservation of aDNA going back to the Mesozoic Era when non-avian dinosaurs lived is entirely unknown; since DNA is a complex molecule that breaks down easily, even in a relatively preserved environment like inside amber, it will become damaged and unreadable at such timescales.) Using this material, they’ve created a park with living non-avian dinosaurs and pterosaurs that they intend to show is safe for visitors who want to see these animals. When industrial sabotage from another biotech corporation leads to a systems shutdown and widespread animal breakouts leading to many deaths, the various protagonists all have to struggle to bring things back under (the illusion of) control and, when that fails to occur in any definite way, to escape and destroy the situation that’s been created.

Michael Crichton’s interest in the state of science he’s commenting on is clear throughout the text and he comments sometimes specifically on certain developments in paleontology, genetics, and even computing. There are a lot of comparisons to be made between the novel and Frankenstein in its unease with the direction of unchecked science and the inability of InGen to properly reckon with what it’s done. Importantly, since the novel went on to become a best-seller, it was extremely impactful on how audiences saw the idea of de-extinction and for most readers was probably the first time they’d really considered the idea. While the novel seems to take the strong stance that bringing back dinosaurs without really knowing what that entails is a dangerous and reckless idea, plenty of readers also got the opposite notion that the idea is really cool. Both of these takeaways exploded in popularity three years later when Steven Spielberg’s movie adaptation of Jurassic Park hit theaters and became the highest-grossing movie of all time released up to that point.

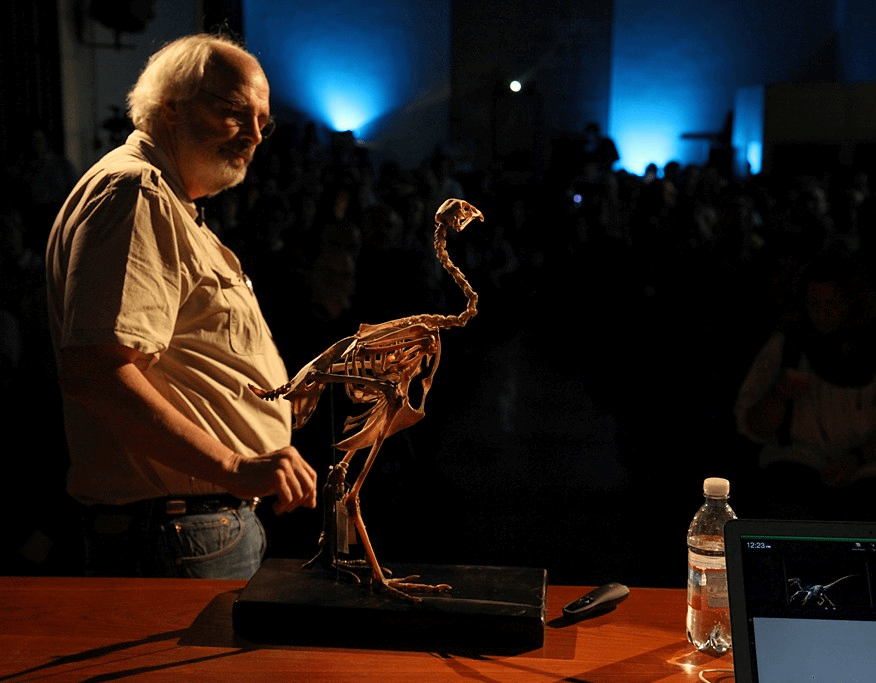

Paleontologist Jack Horner with a bird skeleton in Milan, Italy, posted by the Flickr account of the Meet the Media Guru event.

While the world went crazy over Jurassic Park, one paleontologist managed to find his way to the center of attention over it. In the 1970s, Jack Horner made news by publishing on the nesting habits of the large Late Cretaceous hadrosaur (a group of duck-billed herbivores) dinosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum, whose fossils and nests were found in large numbers in the Two Medicine Formation of Montana, USA, from some 75 million years ago. This discovery provided the first direct evidence that at least some non-avian dinosaurs nested in large colonies like many modern birds and also that they provided parental care for their young. It was a particularly important development in the Dinosaur Renaissance, an overturning of how dinosaurs were thought about in this period that changed the paradigm from slow lumbering reptiles to fast-moving warm-blooded intelligent creatures more like birds. Crichton was familiar with Horner’s work and even wrote the paleontologist in Jurassic Park, Alan Grant, to have worked on this same Maiasaura discovery with Horner, who is mentioned by name in the text. When Spielberg produced his movie adaptation, Horner became the paleontological advisor for the movie and then later for its sequels. (It is also around this time that Jack Horner took the public position that he is now infamous for in paleontology circles, suggesting that Tyrannosaurus rex was an obligate scavenger, which he has used his platform to push despite that position being widely considered completely contrary to the evidence by experts specializing in the animal.)

The same year that the original Jurassic Park movie released, a NOVA documentary titled “The Real Jurassic Park” featured both Jack Horner and Bob Bakker, probably the most notable figure of the Dinosaur Renaissance (mentioned in both the novel and movie script of Jurassic Park), discussing the possibilities of piecing together the genetic material of dinosaurs, creating viable embryos, and then caring for and managing the creatures that result. The documentary is narrated by Jeff Goldblum, who plays the naysaying mathematician Ian Malcolm in Spielberg’s film, and frequently includes commentary from Michael Crichton himself. At the time, there was increased interest in the soft tissue of dinosaurs and Horner shows off the fossilized bones of a Tyrannosaurus on which microscopic chemical research was being done. At the time, it was considered a real possibility that the field of dinosaur paleontology, which was increasingly diversifying outside of just studying fossilized bones, might make real leaps in finding preserved prehistoric biochemistry and maybe even that elusive DNA. Horner and the like considered the possibility that it would be found in any undamaged state, however, to be extremely unlikely and so the documentary cuts to Bakker who explains another idea. Birds, as the direct descendants of dinosaurs (and which are, within modern phylogenetic classification, dinosaurs themselves), have many legacy traits that are simply dormant within the genetic code. Even by the time of this documentary, geneticists had for example identified a gene that could produce tooth-like structures in chicken embryos. It was hypothesized that a reconstructed dinosaur might have a combination of paleo-DNA and the engineered DNA of modern relatives, grown in a special incubation facility. Beyond that would lay further challenges such as ensuring the animal’s immune system could survive modern microorganisms, producing enough food in the proper manner to keep it fed, having a working climate, and creating contingency plans for animal escapes.

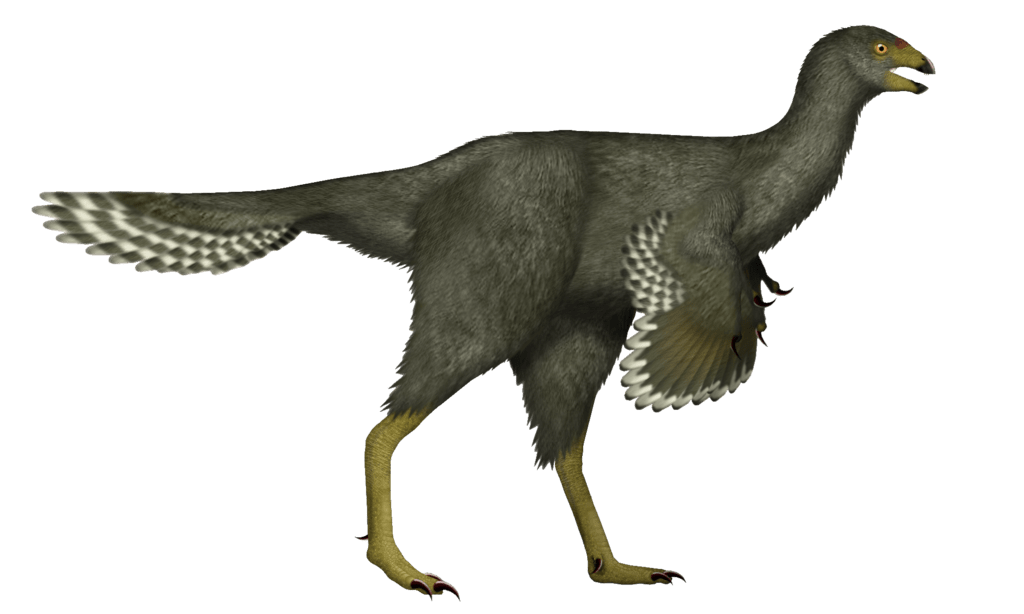

In the coming years, scientists largely came to agree that actually getting DNA from that far back was effectively impossible, with a liberal upper limit for DNA that can be sequenced at around 1.5 million years old, though most samples are severely degraded long before that. But the idea of engineering a bird remains plausible. Horner began to focus on maniraptoran dinosaurs, animals like Velociraptor, which were closely related to the lineage that became birds. In his 2009 book How to Build a Dinosaur: Extinction Doesn’t Have to Be Forever (a book which was somewhat inspired by his early access to a very early version of the script for Jurassic World, the fourth movie of the Jurassic Park cinematic franchise, which eventually released in 2015), he explored the idea further of a “Chickenosaurus.” A dinosaur created by modifying a chicken to have traits such as sharp teeth, a long tail, and grasping fingered hands would not be a revived ancient species of dinosaur by any means, but it could have a lot in common with one and the genetic research into making one could have positive effects for future genetic science, including potential applications in cancer medicine. The Chickenosaurus project did begin and saw successes at triggering genes in chicken embryos, furthering science and understandings of gene expression. That it was largely funded by George Lucas, director of Star Wars, shows, I suppose, once again how deeply tied up these interests are with cinema and the relationship science-fiction and science have in our modern world. Horner predicted that a Chickenosaurus would exist in about ten years, but 2019 came and went with no such creature.

A restoration of the Chinese Cretaceous dinosaur Caudipteryx zoui by Wikimedia contributor UnexpectedDinoLesson. Like with several other types of feathered dinosaurs, Caudipteryx fossils preserve some structural pigmentary data that allow us to have some idea of the coloration and patterns it may have had in life.

Jurassic Park looks more unlikely than it did when Crichton released his novel, but that doesn’t mean the discourse around it hasn’t been important in significant ways. Much as we justifiably valorize the scientific process as an amazing tool of knowledge generation and assessment, it is at the end of the day a cultural construct and is carried out entirely by humans within the cultural zeitgeist of society. Jurassic Park has now been the standard for how the public understands dinosaurs for more than three decades and it looms large in both scientific and popular circles. For the recent history of de-extinction, it sets widespread expectations for what is entailed, it generates excitement about the awesome power of science and ancient animals, and it also provides the most powerful criticisms as to why the practice might be dangerous. For those interested in microscopic studies of ancient dinosaurs though, amazing things have come from them in recent years, such as a better understanding of the structures and even pigments of many dinosaur feathers, such that they can be reconstructed in an approximation of true color. One of these feathered dinosaurs which has been extraordinarily preserved is Caudipteryx, which lived in Early Cretaceous China around 125 million years ago. In 2021, a team of scientists in China published that microscopic studies of fossilized cartilaginous structures from the animal in exceptional silicate preservation revealed not only identifiable cells but identifiable cellular nuclei, including preserved chromatin (the material formed of DNA when it clusters together) structures in cells that were undergoing mitosis (cell division). This isn’t DNA in any form that can be sequenced but… I think it is clear we still have a lot to learn and which can be learned.

Constructing a Lost World

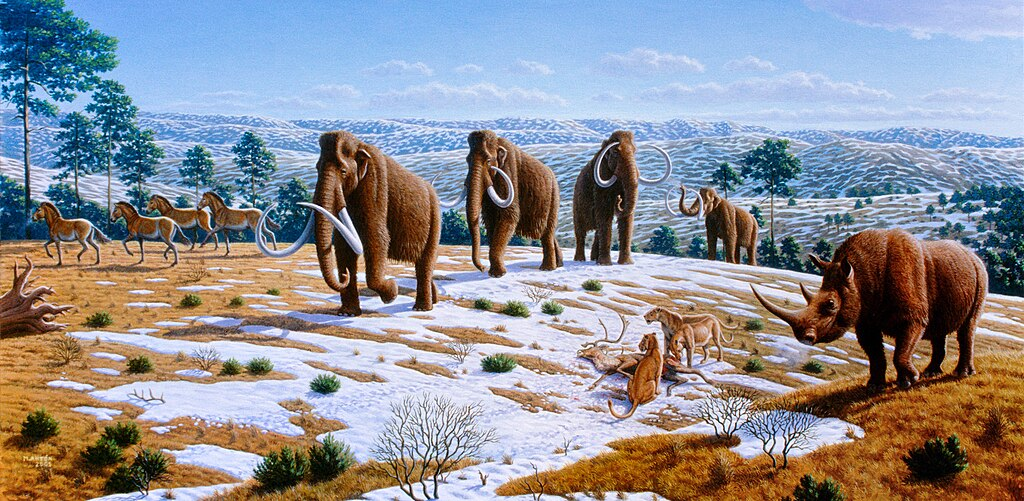

This illustration by Mauricio Antón depicts a steppe landscape and some of the animals of northern Spain in the Pleistocene. Among the extinct fauna here are the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), and the cave lion (Panthera spelaea), while living species include the wild horse (Equus ferus) and the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus).

What if the focal point of restoring what was lost is not put on reviving extinct species but rather in repairing damages to ecosystems that have suffered these losses? When geologists and paleontologists refer to the Pleistocene Epoch, they refer to a period of time between 2.58 million and 11,700 years ago when a series of glacial phases dropped average temperatures, especially in far northern latitudes, and produced vast ice sheets that blanketed large portions of Eurasia and North America. (We are actually still in an interglacial phase of part of this cycle and if you are interested in how this works, I recommend reading my article on this blog about the extinction of the North American megafauna.) During glacial phases, sea levels dropped dramatically and even south of the ice sheets, permafrost permeated the soil, reducing tree growth and replacing boreal forest with a vast steppe tundra, often called the mammoth steppe, which reached from Western Europe across Central Asia and all the way across Beringia and into North America. In Eurasia, nature’s menagerie included the famous woolly mammoths as well as other megafauna grazers such as the woolly rhinoceros and the colossal deer known as Megaloceros. More familiar grazers today included musk oxen, reindeer, horses, bison, and camels. And of course predators such as cave lions and wolves fed on the various herbivores. The large number of megafauna in this region has caused some ecologists to nickname it “the northern Serengeti” and during the last glacial phase this region had somewhere around 100 times the animal density of the modern Arctic.

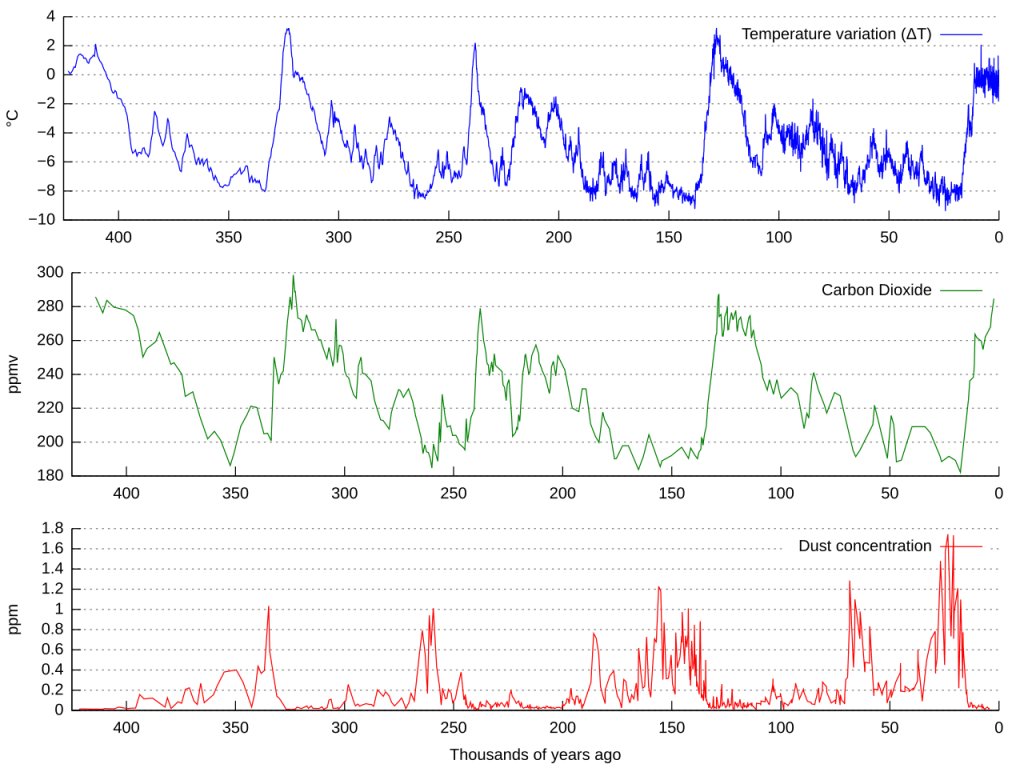

Data compiled by NOAA using an ice core from Vostok Station in Antarctica, displaying global average temperature variation (compared to “pre-industrial averages,” that is, the average global temperature just prior to the Industrial Revolution) over the last 420,000 years, as well as carbon dioxide and dust concentrations in the atmosphere. Note that the carbon dioxide levels mirror the temperatures, due to feedback loops in both directions.

The secret to this amazing animal density was a beneficial feedback loop that enabled the environment to be “high-productivity,” that is that natural biological resource cycles like plant growth and consumption occurred very quickly. Grasses in particular grow much faster than brushy plants and trees and therefore grasslands can support an extremely dense array of animals compared to, for example, scrubland and forests. Animals eat the grasses and then the grasses replenish. Grazing animals also clean up hay and other dead plant material quickly, meaning that when grasses die, they can quickly be replaced by the next generation rather than piling up. However, grass is vulnerable to the growth of taller plants like bushes and trees which very naturally outcompete it for photosynthesis by reaching higher up and taking the sunlight first. But this is why grasslands rely on grazers to exist: large herbivores that eat indiscriminately will destroy the invading saplings of other plants quickly, but they won’t be replenished as fast as grass. Without grazing animals, much of the world’s grasslands would be inundated with trees, which tend to have the edge on grass in the evolutionary struggle for sunlight. Because grasses don’t have particularly deep roots, they allow soil to build up relatively undisturbed. As a result of this, grasslands (and especially northern tundra which is frozen solid with permafrost underground) sequester, or store, a lot of carbon from decomposing organisms. During the glacial cycle, there is a marked similarity between global average temperatures and carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere. This goes both directions. Not only is carbon dioxide a greenhouse gas that raises temperatures, but as colder climates promote the spread of grasslands instead of forests, these environments sequester more carbon dioxide and remove it from the atmosphere. A sort of natural carbon capture. On top of this, grasslands have a higher albedo, the amount of light reflected back instead of being absorbed into an environment, than scrubland or forest, meaning they result in less solar heat being retained on the Earth’s surface. During the last glacial phase, the mammoth steppe became home to a new type of hunter: first Neanderthals and then Homo sapiens. These hunters perfected new tools to use specifically to hunt megafauna, building whole economies around doing so, evidenced by many finds such as the large mammoth-bone structures at Mezhyrich, Ukraine from around 15,000 years ago. As the planet warmed after 11,700 years ago, the loss of permafrost and the efficient hunting by our species acted as twin forces to destabilize this dynamic balance between the grazers and the grasses. The result was the rapid expansion of the boreal forest and the decline, and sometimes extinction, of grazing megafauna.

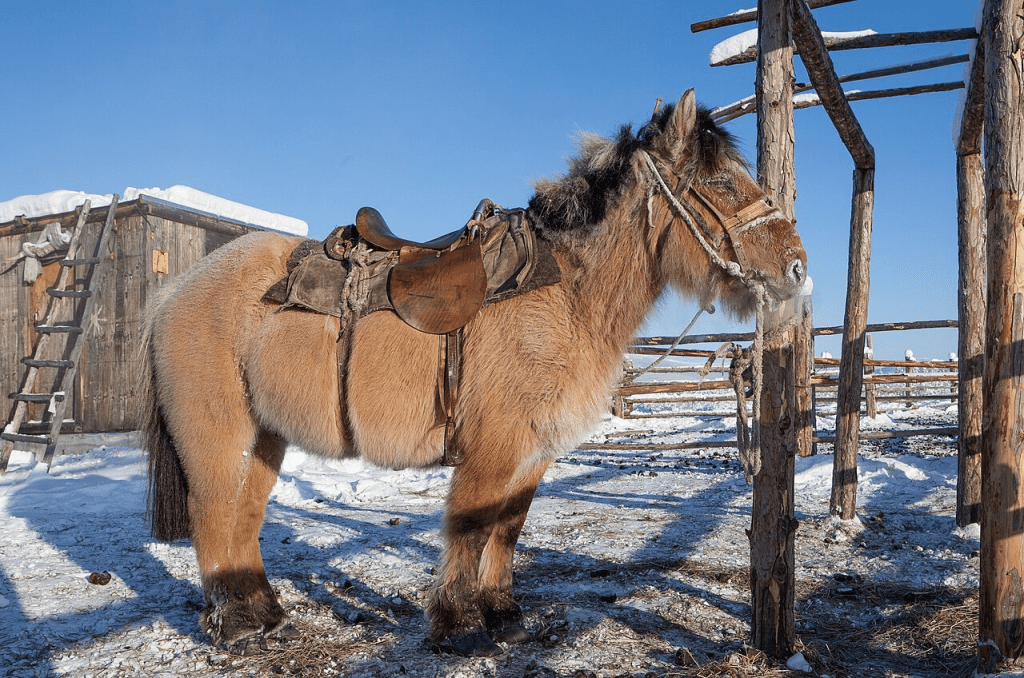

This is a Yakutian horse, a member of a breed of horse adapted for the subarctic environment, in a photo by Maarten Takens.

Our next modern story opens in 1988 in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which was going through a period of dramatic change. While Michael Crichton was writing Jurassic Park in the United States, the Soviet premier since 1985 had been Mikhail Gorbachev, a reformer who believed that if the USSR was to survive, it needed to be far more open to dissenting political views and free speech and in the next year he would opt not to intervene as some of the Soviet Union’s former satellite states in Eastern Europe chose liberal democracy over communist dictatorship. Russian geophysicist Sergey Zimov had made a name for himself in studying permafrost and methane release from Arctic ground sequestration, monitoring from the Northeast Science Station, which he had founded in 1977, a research geological and ecological research facility near the Arctic coast of Russia’s Sakha Republic, an administrative division in northeastern Siberia. He had begun to wonder about the relationship between grassland animals and the preservation of the tundra grassland. So in the cold Arctic basin near the Kolyma River, he released 12 Yakutian horses to the area. (This breed of horses actually has its own interesting story. They are not descended from the prehistoric horses from the region, but rather from horses that were adopted from other domesticated horse populations by the indigenous Yakut people of what is now the Sakha Republic starting around the 1200s AD. Over a relatively rapid period of time, these horses evolved, probably by both natural and artificial selection, to have many Arctic adaptations such as woolly fur, short fat bodies that better preserve heat, and the ability to graze through snow effectively.) This experimentation had to be cut short though due to events thousands of kilometers away in Moscow; Soviet science was very much state-funded and the state was actively breaking down. In 1991, an aborted coup against Gorbachev shook the state to its core as economic malaise drove the country into chaos and newly free elections revealed deep-rooted demand for change among the population. Towards the end of the year, various Soviet constituent republics declared their independence until finally the Soviet flag descended on the Kremlin for the last time on December 26, 1991. The Sakha Republic was inherited by the new Russian Federation.

Zimov came back to the new government to seek support and in 1996 it was granted with the state giving 144 square kilometers to the project, which became an officially registered company. The name of this company, project, and location was, in reference to a popular movie from three years earlier, Pleistocene Park. Zimov wanted to do a proper experiment to see if grazing animals released within a controlled area would promote the expansion of grasses over other plants and aid in the retention of permafrost, sequestering of carbon, and increase in biological productivity. 50 hectares were fenced in so that the local animal populations could be controlled for the experiment. The first animals introduced were Yakutian horses, moose (Alces alces; you might see these called “elk” in some coverages of Pleistocene Park and that is because that is the term generally used in Eurasia for what North Americans call “moose,” which are not the same deer North Americans call “elk”), and reindeer (Rangifer tarandus; this is, yes, the Eurasian name for the same animal North Americans call “caribou”), all animals already found locally. Seeing some initial successes, a decade later the park expanded significantly with a new 2,000-hectare fenced area constructed between 2005 and 2006. In 2010, this expansion allowed for the transportation in of animals which had disappeared in the region. Musk oxen (Ovibus moschatus) are one type of animal which once inhabited Siberia and the mammoth steppe but which disappeared in the region in the last few thousand years, only surviving in the northern part of what are now Canada and Greenland, though reintroduction projects have seen success with them in many parts around the Arctic since 1900. A number of these have been introduced to Pleistocene Park from Wrangel Island (an Arctic island northeast of furthest Siberia, which is actually otherwise notable as the last place woolly mammoths survived about 4,000 years ago), which have over time shifted from feeding primarily on lichens to grass, which is more plentiful in the park now. The ancient steppe had herds of bison in species which have since gone extinct. To replicate this, park authorities first brought in wisent from near Moscow but a breeding population failed to be established so instead American bison are there now. Within the last decade, the park has also come to play host to a variety of domesticated animals including Kalmykian cows (an aurochs-like breed from near the Lake Baikal region), sheep, and goats. The sheep in particular require some keeper support but help to remove weeds. A species there I particularly like is Bactrian camels (Camelus bactrianus), which fill in some of the roles of extinct camels that once inhabited the steppe.

The exciting thing about Pleistocene Park is that the experiment has largely proven its foundational theory. As mosses are eaten up by grazers, they are replaced by grasses, which then increase the nutrient productivity that allows even more animals to graze and sequester more carbon while at it. Another effect, which is less straightforward to understand, is that grazing animals help to preserve permafrost in the area. The reason for this is that higher populations of grazing animals mean snow cover, which is often present in the subarctic (average temperature in January at the park is -33°C and in July 12°C), gets trampled down. Snow is actually a major insulator and prevents the cold air above from cooling the groundwater below, meaning that having animals clear it better preserves the ice underneath. One activity Pleistocene Park has actively carried out is the monitoring of this permafrost. A large network of tunnels more than 200 meters long was constructed at the park’s base camp between 2012 and 2016 and, aside from storage, it is used to monitor the rate of permafrost degradation, which despite having been successfully slowed in the park’s experimental conditions is still displaying long-term damage from the current global process of climate change. As the ice thaws, carbon dioxide comes out, adding more greenhouse gases to a warming atmosphere. Secondarily, as large amounts of organic matter which has been frozen for long periods of time becomes available to microbial decomposers in the soil, the decomposition process releases methane, which is a far more potent (but shorter-lasting) greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

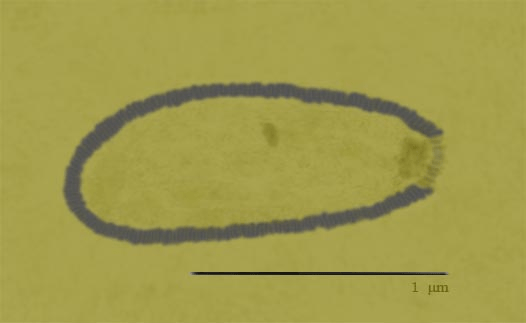

A microscope sketch of the majestic Alphapithovirus sibiricum by Wikipedia contributor Pavel Hrdlička.

Speaking of microbes, so far we have only discussed the de-extinction of animals and environmental reconstruction involving animals. Let’s talk about accidental de-extinction that is already happening: ancient viruses. When ancient animals like mammoths and recently the saber-toothed cat Homotherium are found in permafrost, they are very much not alive and while DNA can be recovered (more on that soon) from them, freezing living tissues actually ruptures the cellular microstructures that make life possible. This is far less a problem for much simpler biological entities, viruses, which the ice can actually help preserve. As climate change has been thawing permafrost, prehistoric viruses have already been emerging and recorded by science. Accidental de-extinction has a real risk of bringing ancient pathogens to life (although maybe “life” is the wrong word for viruses but that’s another issue). The first such virus to be rediscovered this way was Alphapithovirus sibericum, a DNA-based giant virus (or “girus”) measuring about 1.5 micrometers in length, making it one of the largest viruses ever discovered, which appeared in a 30,000-year-old segment of a permafrost ice core from Siberia in 2014. Samples of the virus were found to infect amoebae (this is a blanket term for single-celled eukaryotic organisms with a flexible shape), so it probably participated in the microbial environment of its day infecting one of the most common eukaryotic organism inhabiting the world’s soils: Acanthamoeba. Since then, scientists have identified various other viruses from permafrost which also prey on this readily available amoeba, some of which are otherwise extinct and some of which still exist elsewhere in our world. While these amoeba-hunting pathogens are not really a threat to us, we already have reason to believe that potential paleo-epidemics may be waiting in the thawing ice. Between just 1897 and 1925, around 1.5 million deer were killed by a series of anthrax outbreaks in northern Russia and the remains of many of these animals are still waiting in the permafrost. Likewise, in thousands of settlements in the region, farmers have long designated places to bury cattle which died from the disease to prevent their spread to others and to humans, but now these sites have become ticking time bombs. An outbreak in the Yamal Peninsula in 2016 which infected thousands of reindeer and even humans is thought to have been linked to a thawing reindeer corpse from the previous century. What will happen when the deeper layers from the Pleistocene thaw out more and more? Will ancient diseases from the carcasses of mammoths and woolly rhinos be unleashed on immune systems that have not dealt with them for tens of thousands of years?

Obviously, Pleistocene Park is not a de-extinction project in the way that a lot of the other things I am discussing here are. It does not purport to resurrect any organisms that no longer exist but instead reconstructs (albeit imperfectly) former ecological conditions. The relationship this has with de-extinction though is important, because the reality is that if an extinct animal were to be brought back and rewilded, its survival would depend on ecological conditions that may not still exist in this world today; in fact, the disappearance of such conditions is likely the reason for its extinction. (An interesting philosophical issue emerges here about our relationship with nature too: as our planet is thoroughly dominated by human activities now, increasingly even wild spaces are specifically designated or built by us. Even conservation becomes management rather than preservation. The strict distinction between natural and built environments remains a bit of an illusion. Perhaps moving forward, we will have to find ways to be comfortable with this for both our survival and that of the fellow inhabitants of our planet.) In popular discourse, the favorite animal to imagine a return for is probably the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), an animal deeply dependent on the tundra steppe environment that Pleistocene Park is building. And Zimov himself has suggested that if the mammoths do make a return, the park might be a suitable trial location for them to make their first wild steps again.

Me with the woolly mammoth statue at the Royal British Columbia Museum. I am truly in awe to be in the presence of the greatest of God’s creatures. I want one.

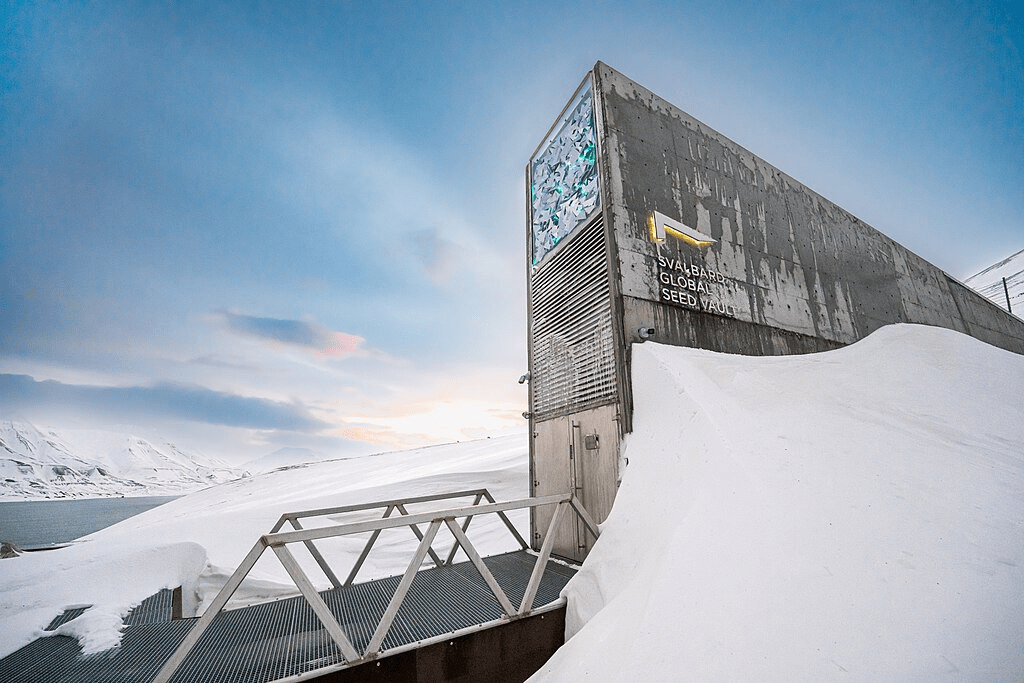

During the Pleistocene, there were many species of mammoths, elephants of the genus Mammuthus which were related to the modern Asian elephant, actually more so than either is to African elephants. The woolly mammoth was just one species of these which was extremely widely distributed in the steppe tundra environments that crossed the length of Eurasia and even extended across Beringia into subarctic North America. Assuming behavior similar to modern elephants, these mammoths’ females and young would have formed large cooperative herds while males wandered and looked for mates, sometimes battling each other in testosterone-fueled displays. With a combination of intensive human hunting and the aforementioned ecological cascade related to climate change, woolly mammoths went extinct on the mainland about 10,000 years ago but a final population existed on Wrangel Island off the northeast coast of Siberia until only 4,000 years ago (for the human-history fans keeping track at home, this is around the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur in Sumer or the start of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt) where they died off possibly prior to human arrival. Throughout human history since, the inhabitants of the mammoths’ former range have often known about their remains and the origins of the very word “mammoth” are unclear because it was already being used for tusks found in Siberia in the 1600s, presumably by way of indigenous people who had already been familiar with them before Russia’s eastward expansion. It was in a paper in 1796 by French biologist and “father of paleontology” Georges Cuvier that the concept of a species going extinct was first proposed in modern scientific literature. Woolly mammoths are almost uniquely tied to our cultural concept of extinction in that the biological concept of the matter was first defined to describe what had become of them. As such, for many they are the quintessential creature for which extinction can be conquered. As an animal which only lived a few thousand years ago and in environments where permafrost has existed consistently since then, woolly mammoths are fairly strong candidates for de-extinction in a lot of ways. We have their complete remains and know what they looked like pretty much entirely, including both their outsides and their entire internal anatomy. We have a bounty of genetic information from a large number of individuals, meaning it is even possible to do genetic diversity studies of mammoth populations. And we know a very high amount about the environments they lived in and what else lived there. As of writing this, efforts to revive the mammoth have not gotten very far but ambitious projects exist in Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the USA. We will explore some issues related to these later, but for now, here is the hypothetical process for bringing back the woolly mammoth as generally understood today.