In Homer’s Iliad, the following lines appear from Book 20, line 455 until the end of the book. The Greek hero Achilles is raging in battle against the Trojans following the death of his beloved Patroclus. Finding Hector, the Trojan hero who slayed Patroclus, Achilles attempts to get his vengeance but divine intervention takes Hector away from him. What follows is one of the most visceral descriptions of serial violence you will ever see in an ancient source as Achilles drops a truly spectacular body count on the battlefield. Despite mostly being characters unimportant elsewhere in the epic, his victims are given names and backgrounds, emphasizing the tragic deaths of people in war. This translation is from that by Augustus Taber Murray for the Loeb Classics Library.

So saying he smote Dryops full upon the neck with a thrust of his spear, and he fell down before his feet. But he left him there, and stayed from fight Demuchus, Philetor’s son, a valiant man and tall, striking him upon the knee with a cast of his spear; and thereafter he smote him with his great sword, and took away his life. Then setting upon Laogonus and Dardanus, sons twain of Bias, he thrust them both from their chariot to the ground, smiting the one with a cast of his spear and the other with his sword in close fight. Then Tros, Alastor’s son–he came to clasp his knees, if so be he would spare him, by taking him captive, and let him go alive, and slay him not, having pity on one of life age, fool that he was! nor knew, he this, that with him was to be no hearkening; for nowise soft of heart or gentle of mind was the man, but exceeding fierce–he sought to clasp Achilles’ knees with his hands, fain to make his prayer; but he smote him upon the liver with his sword, and forth the liver slipped, and the dark blood welling forth therefrom filled his bosom; and darkness enfolded his eyes, as he swooned. Then with his spear Achilles drew night unto Mulius and smote him upon the ear, and clean through the other ear passed the spear-point of bronze.

Then smote he Agenor’s son Echeclus full upon the head with his hilted sword, and all the blade grew warm with his blood, and down over his eyes came dark dearth and mighty fate. Thereafter Deucalion, at the point where the sinews of the elbow join, even there pierced he him through the arm with spear-point of bronze; and he abode his oncoming with arm weighted down, beholding death before him; but Achilles, smiting him with his sword upon his neck, hurled afar his head and therewithal his helmet; and the marrow spurted forth from the spine, and the corpse lay stretched upon the ground. Then went he on after the peerless son of Peires, even Rhigmus, that had come from deep-soiled Thrace. Him he smote in the middle with a cast of his spear, and the bronze was fixed in his belly; and he fell forth from out his car. And Areithous, his squire, as he was turning round the horses, did Achilles pierce in the back with his sharp spear, and thrust him from the car; and the horses ran wild.

As through the deep glens of a parched mountainside rageth wondrous-blazing fire, and the deep forest burneth, and the wind as it driveth it on whirleth the flame everywhither, even so raged he everywhither with his spear, like some god, ever pressing hard upon them that he slew; and the black earth ran with blood. And as a man yoketh bulls broad of brow to tread white barley in a well-ordered threshing-floor, and quickly is the grain trodden out beneath the feet of the loud-bellowing bulls; even so beneath great-souled Achilles his single-hooved horses trampled alike on the dead and on the shields; and with blood was all the axle sprinkled beneath, and the rims round about the car, for drops smote upon them from the horses hooves and from the tires. But the son of Peleus pressed on to win him glory, and with gore were his invincible hands bespattered.

The Iliad is often framed as the opening work of the canon of western literature. Along with the often-associated Odyssey, it is the most famous of a whole collection of Greek and Roman works set in and in relation to the Trojan War, a conflict that this body of literature does its best to present as the most extreme war imaginable. It has the most impressive heroes and also the greatest tragedies, all fought in ten years of colossal bloodshed on the same battlefields, ending in victory for the Greeks by the strange stratagem of a huge wooden horse and the destruction of a great city. All the while the gods themselves drive events on the battlefield based on their personal struggles against one another, heaping more deaths upon mortals through great and terrible divine intervention that emphasizes even their own moral failings. In the aftermath of the war, its great heroes are all killed or face ill fortunes on their way home, with a few exceptions, some of which have foundational narratives in the Greco-Roman world. How did this happen? Why does these classical civilizations have such an insanely traumatic war narrative written about this one very real place? How much of it happened and what evidence is left and what is the relationship between myth, legend, and history when it comes to reconstructing the past?

Before we answer these questions, let’s indulge in a quick run-through of the myths. I will include references to which texts provide the most well-known version of a given episode so we can appreciate the amount of authors and oral storytellers who have participated in producing the Trojan War myth and have some reference point when we talk about its development later.

The Trojan War

(Jacob here with a note before we even start. I’m going to use “Greeks” when referring to the people that in many translations of Homer are called “Achaeans.” This is for the purposes of familiarity to an English-reading audience but remember the word “Achaeans” since it will be important later. To spoil a little, this narrative would have taken place in what we consider the Mycenaean period of Aegean civilization, but later storytellers introduced elements more familiar to their own periods. It is up to you if you imagine these characters in Bronze Age, classical, or neoclassical fashion. Also… if you are currently reading or soon to read anything related to Greco-Roman mythology, I am about to spoil a lot of myths. Be forewarned.)

The Judgement of Paris in a fresco from the Roman city of Pompeii, made in the first century AD and then preserved when the city was blanketed in volcanic ash in 79 AD. From left to right the figures here, using the Latin names the Romans would have used, are Juno (Hera), Venus (Aphrodite), Minerva (Athena), Mercury (Hermes), and Paris.

(The opening episode of this heroic cycle is generally called the Judgement of Paris and is recounted in a variety of sources, most of which seem to be drawing from the now-lost Cypria of the 600s BC, though a short version of it is told in the Iliad of the 700s BC, showing it was already around before that. Some sources provide background on major characters of the Trojan War cycle that takes place before this but for simplicity’s sake, we’re going to start here. The final form of the story most recounted is from Euripides’s play Andromache of the 400s BC.) It was a time of merrymaking for both gods and mortals when Peleus, king of Phthia (a settlement somewhere in Thessaly that modern scholars have not identified), was set to marry the Nereid (sea nymph) Thetis. Zeus, king of the gods, hosted the banquet himself. Eris, the goddess of discord and strife, was strategically left out of the invite list because of her habit of making everyone miserable. She was not happy about this exclusion and so hatched a plan to incite problems for everyone. She inscribed the words “to the fairest” on a golden apple and rolled it down a table so that it settled in front of three goddesses: Hera (sister-wife of Zeus and goddess of marriage), Athena (goddess of wisdom and battle strategy), and Aphrodite (the goddess of love and beauty). The three goddesses bickered about who was the intended recipient and when they took the issue to Zeus, he redirected them to be judged by Paris (named Alexander in some sources), prince of the city of Troy on what is today the Asian Turkish side of the Bosporus. Each of the goddesses decided to sweeten the deal by promising Paris something if he would choose them. Hera offered to make him king of Europe and Asia while Athena offered him wisdom and battle glory. Aphrodite meanwhile offered him Helen, the daughter of Zeus and most beautiful woman in the world, at present married to King Menelaus of Sparta. Paris went with that last option and then made his way to Sparta.

The sacrifice of Iphigenia as depicted on a wall fresco from… drumroll… also Pompeii, though this is possibly a copy or based off of a famous painting by the 300s BC Greek painter Timanthes, who made an apparently famous depiction of the scene that was commented heavily upon by Roman writers, which matches the description of this painting in many features. Agamemnon is weeping on the left while Iphigenia is carried to be sacrificed by servants.

(Ancient Greek sources do not agree if Paris kidnapped Helen or if she went with him willingly. What follows here is mostly from the Iliad which refers to it in expository backstory, even though its plot starts late in the war.) Menelaus and Odysseus, king of Ithaca (a small rocky island off the western coast of Greece), made a trip to talk to King Priam of Troy to try to recover her diplomatically, but they were refused. Menelaus then called upon Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, to call up the other Greek states to war, remembering old vows to protect the marriage of Helen and Menelaus. Thus Helen became “the face that launched a thousand ships” as the Greek world descended upon Troy. The Iliad lists 1,186 ships with 46 military captains from different parts of the Greek world. Odysseus left behind his wife Penelope and their newborn son Telemachus, just as many other Greeks left their homes and families for the other side of the Aegean. A son of Peleus and Thetis named Achilles was hidden from the war by being disguised as a woman but Odysseus managed to identify him when he bravely came out to fight after Odysseus feigned an attack. This was the first time these two men would meet and they would go on to become the two most famous heroes of the epic cycle, renowned and feared in different ways. On the way over, Agamemnon, who had become sort of the general commander of the whole Greek coalition, angered the hunting goddess Artemis by killing a sacred deer. Artemis prevented the Greeks from reaching Troy until Agamemnon would sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia. So he prepared to sacrifice her until Artemis (in some versions) came and rescued her, allowing the army to continue afterwards.

(The landing narrative is given by Apollodorus and Pausanias in the 100s BC.) A prophecy had said that the first Greek to land on Trojan soil would be the first to die so as the Greek ships gathered at the coastline, there was hesitancy to disembark. Finally crafty Odysseus jumped off and landed on his shield, prompting others to follow him. A captain named Protesilaus was the first to actually land on Trojan soil and he was promptly killed by the Trojan hero Hector in the ensuing battle. Greek sources essentially unanimously agree that the war lasted around ten years, however aside from narratives of the war’s origins, almost all of the popular narratives occur in the last incredibly bloody year of the war. So forgive me if it feels like I am going to skip about nine years here soon. The ancient Greeks made me do it. There are some hints in the Iliad that wider strategies were employed in this time, such as Achilles and Ajax distinguishing themselves by leading expeditions to conquer Trojan allies. But the major problem the Greeks faced which frustrated them was that Troy had colossal defensive walls that made it impregnable. Long before, the sea god Poseidon and the prophecy god Apollo had both been involved in a failed conspiracy against Zeus, who punished them with a year of forced service to a Trojan king named Laomedon. The king had made the gods build great walls beyond the skill of mortal man. After nine years of no success at taking the city and distress from a lack of necessary supplies, many of the Greek troops mutinied, pushing Agamemnon to allow them to go home. Achilles, by now recognized as the fiercest soldier in the coalition, was instrumental in threats and coercion to make them stay and fight longer. Nevertheless, the situation was hell for the Greeks and misfortunes were only beginning.

(Here begins the plot of the Iliad. This is also your suggestion to go read the Iliad because it is amazing. It tells what I am going to tell better and in 24 books of dactylic hexameter. This is also where I want to point out that the Greek term “hero” did not have the moral connotations it has today; you will notice that all these heroes are terrible people and I am not trying to glaze them by using that term.) At some point, Agamemnon came into possession of a Trojan woman named Chryseis, daughter of a priest of Apollo named Chryses. When Chryses came to request she be returned, Agamemnon insulted the man, prompting him to pray to Apollo for vengeance, which was apparently extremely effective because a plague fell over Agamemnon’s forces. Agamemnon was no stranger to his war efforts being subject to divine thwarting before and returned Chryseis to end the plague. To make up for his lost concubine, he took that of Achilles, a woman named Briseis. Achilles got extremely angry about this and refused to fight. In his absence, the Greeks began taking heavy losses in the field and soon the Greeks and Trojans found themselves in a stalemate which allowed both armies to gather in the field. In the ensuing truce, Menelaus and Paris had the opportunity to duel to settle the score. Menelaus was about to triumph but Aphrodite intervened to snatch Paris away and then both armies met in full field combat. In the battle that followed, the Greek hero Diomedes charged forward, threatening the Trojan hero Aeneas (son of Aphrodite, who snatched him away) and even winning a match of single combat with the war god Ares. The Trojans however made gains and pushed back all the way into the Greek camp, threatening to burn the ships.

(Still the Iliad.) The Greeks pleaded with Achilles to rejoin their efforts and save them from the wrath of the Trojans, led by their hero the prince Hector. (Hector is actually one of the only heroes in this narrative portrayed in consistently very flattering moral terms, a good man defending his city, even while a mighty warrior. I personally find the fact that Greek writers put this man on the “enemy” side of the story to be extremely interesting.) Achilles relented and allowed his companion Patroclus to join the battle wearing Achilles’s own armor. Patroclus had great success and the sight of him struck terror into the Trojans, driving them as far back as the gates of the city. There it was Hector who stood bravely and faced Patroclus at the front, taking him on in single combat and winning. The victorious Hector then took possession of the armor of Achilles as the Greek assault broke.

Achilles tending to Patroclus on red-figure pottery from around 500 BC. Some scholars consider these men to have been models of non-romantic friendship between two men. Other scholars suggest they were a romantic pair. The artist here may have accidentally embodied this debate in the way it is impossible to tell if Achilles’s eyes are on the bandages he is applying or Patroclus’s fully exposed penis.

(If you are already familiar with the story, you likely found that my use of the word “companion” for Patroclus was doing some interpretive diplomacy. This is the paragraph where I talk about the interpretation of Achilles and Patroclus in relation to scholarship on homosexuality in ancient Greece. Often in discourse on this online, I see people complaining about this discourse being modern revisionism, even though it has been going on for more than two millennia. If you want to be the person who complains that I want to talk about the history of sexuality for a short blurb out of this long piece about other things, I invite you to grow up. The Iliad actually does not give Patroclus a strong characterization outside of the scene that leads to his death which leaves a lot of wiggle room for readers to imagine their history together. Within the epic, Achilles refers to Patroclus as a therapon, his closest intimate companion, and an equal, despite the fact that Achilles clearly outranks him in the military organization. Patroclus is characterized as gentle and kind in contrast to the wrathful Achilles and capable of calming the hero down. Both men are unmarried, though obviously and relevantly here Achilles makes use of female concubinage. When Patroclus goes into battle to force the Trojans back, Achilles prays to Zeus that he remains unharmed, a prayer that is not fulfilled. And when Patroclus’s body is recovered, Achilles throws himself upon it and weeps, his men fearing that their champion will commit suicide. No other male-male relationship in the epic poem is portrayed with this intensity. In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, written in the 300s BC we learn that in the tragic play Myrmidons by Aeschylus of the previous century (which has since been lost), Achilles and Patroclus were portrayed in a pederastic relationship. Pederasty in ancient Greece was an erotic-and-mentor arrangement involving a younger boy (eromenos) and an older man (erastes), which was typically temporary and ended when the younger participant married a woman. It simultaneously demonstrates that there were public modes of acceptable homosexuality in ancient Greece but also that it was subject to social constraints and the parameters were often not in line with the values of consent and mutualism encouraged in the queer community today, so keep that in mind if you want to use classical examples in representation. Aeschylus apparently represented Achilles as erastes and Patroclus as eromenos, but Plato’s character Phaedrus actually argues that it is the other way around with the bearded Patroclus being older and the youthful and wrathful Achilles being the junior member of the partnership. In later periods, sexual readings of the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles became de-emphasized due to discomfort readers had towards the topic and the fact that the Iliad, the most important work related to them, leaves much space for interpretation. In recent years, queer readings of the story have become common, both in the academic and popular spheres. Opinions are often strong on the matter and in the end and for the sake of this article, the view I choose to hold is this: whatever the historical basis of the Trojan War, the characters as they appear in the Iliad are fictional. You can decide their relationship with each other in your version of the story. The ancient Greeks themselves disagreed on it after all.)

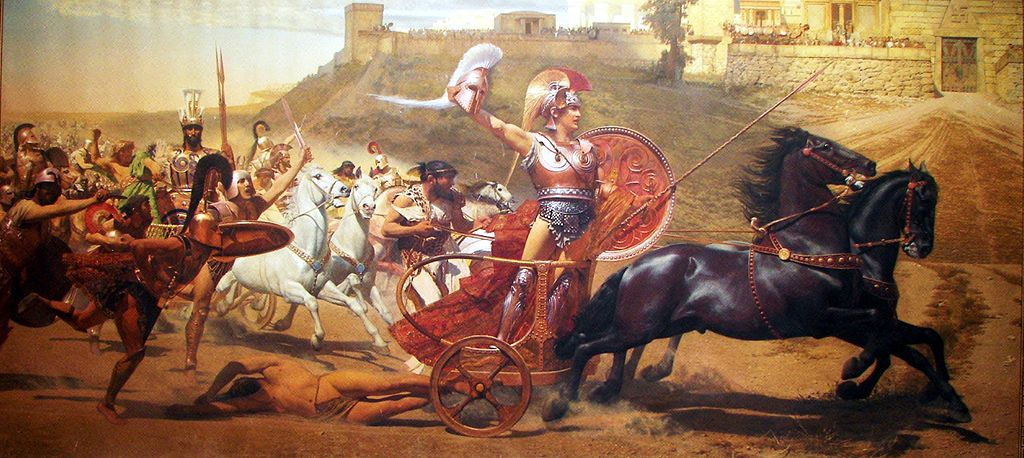

This painting of Achilles dragging the body of Hector around the walls of Troy is from a palace built by Empress Elisabeth of Austria, wife of Franz Josef I, which was built in the 1890s on the island of Corfu in modern Greece. It is an excellent example of the classical themes of painting from the European Romantic period.

(Back to the plot of the Iliad.) Achilles was wracked with grief over the loss of Patroclus and resolved to join the battle again. He made up with Agamemnon, even receiving Briseis back, and got a new array of armor. Achilles’s descent and rage upon the battlefield manifested as a killing spree and it is amidst this that the scene at the opening of this article takes place. The Iliad is simultaneously extremely impressed with its heroes who inspire awe on the battlefield and to readers while also being mournful about the amount of slaughter going on. There is a reason it is read as both a great war story and a deeply thoughtful antiwar piece. I think there is validity to both within the compiled text. The Trojan army fled before Achilles’s wrath and reentered the city but Achilles found Hector standing around outside the city walls. The two met in battle and in the end Achilles defeated him. Taunting the Trojans with their hero, Achilles tied up the body of Hector to his chariot and dragged it around the city. After some more of Achilles’s pettiness, Priam managed to negotiate the return of Hector’s body and a truce allowed for the burial of him and the others lost on both sides of the story. Here ends the Iliad.

(What follows comes from many sources and it is difficult to individually attribute everything, especially when the sources are all themselves participants in a dynamic self-commentating tradition and many of them are lost and cited by other writers. A relatively extensive compilation exists in the form of Quintus of Smyrna’s Posthomerica from the 200s AD, an epic poem which acts as an expanding sequel to the Iliad using materials from many other texts.) In the final days of the war, various foreign allies to the Trojans made their appearance. First were the Amazons, warrior women from Asia led by their queen Penthesilea. There is disagreement over the way this battle played out but in a popular version Achilles killed Penthesilea and then wept for her beauty. A second foreign intervention involved Memnon, king of Ethiopia. (“Ethiopia” here is not the country you know. The Greek word “Aethiopia” refers to all of Sub-Saharan Africa, which was known about but exotic within the Iron Age Aegean world. It is much later Greco-Roman writings from the first century AD onwards describing the Aksumite Kingdom that put the name “Ethiopia” as referring to its roughly modern location.) Within the mythos, Memnon was a great conqueror and model soldier who had campaigned as far as India, Persia, and the Caucasus but displayed great humility. When his army came to Troy, its soldiers were innumerable and came from distant corners of Africa and Asia. He feasted with Priam and then joined the battle as his ally, Memnon fighting at the front of the army. There he killed a Greek prince and was subsequently challenged by Achilles, who defeated the great conqueror in a duel. But here the gods decided it was Achilles’s time to die and Apollo guided the hands of Paris, watching from a nearby vantage point, as he loosed an arrow that struck Achilles in the exposed heel, from which he bled out and died. (Yes, gym bros. The “Achilles tendon” is right there, yes. Also, while the “Achilles heel” as an expression of the single weakness of an otherwise impenetrable person, you may be surprised to learn, as I was, that the idea that Achilles’s heel was his only weakness is largely nonpresent in Greek literature about his death. Apparently the idea that his mother Thetis dipped him in the River Styx as a baby to make him invulnerable but her hand covered his heel comes from the Latin writer Statius in the first century AD. That’s a Roman original addition.)

(What follows is referred to retrospectively in the Odyssey but also recounted by the likes of Pindar and Aristophanes, both in the 400s BC.) As Achilles lie dead on the battlefield, it was Ajax and Odysseus who pushed forward against the Trojan tide. Ajax held off many men while Odysseus dragged the body back to camp. Afterwards, a contest broke out between these two heroes for Achilles’s armor and it was considered that it should go to the smartest warrior among the Greeks. Agamemnon refused to pick between the two and put it up to a secret vote, which Odysseus won. Ajax, filled with rage, set out to kill his comrades but slaughtered two rams in confusion instead, thinking they were Agamemnon and Menelaus. Coming to his senses and realizing what he had tried to do, Ajax was horrified and fell on his own sword, killing himself. Yet another tragic death in this horrible war. Not long later, Philoctetes, a famed Greek archer who had been a late associate of Heracles (that’s Hercules for you Latinists out there, who was apparently just one generation before the set of heroes in this story), loosed an arrow that killed Paris. Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, managed to get inside Troy and contact Helen, making escape plans with her before sneaking out of the city with the Palladium, a wooden effigy of Athena said to grant Troy divine protection. The end was approaching for the city.

This vase from Mykonos dating back to around 670 BC is the oldest known depiction of the Trojan horse. Image from Travelling Runes on Flickr.

(This comes from the Odyssey as well as other sources like the Posthomerica. The horse narrative is extremely well expanded upon across the literary tradition and is likely the most famous aspect of the war to you the reader. The Romaboos among you may know parts of this sequence from the Aeneid.) It was then that Odysseus devised a risky strategy to win the war. He advised the Greeks to build a large wooden horse as a peace offering and move all their ships away and out of sight as if to indicate surrender. A select number of elite Greek soldiers would hide inside the horse and allow the Trojans to take it into the city. After celebrations had ceased, they would leave the horse and make their way to the city gates to allow the reassembling Greek armies in. The plan was agreed to and the horse was placed before the city. The Trojans debated what to do with it. The Trojan princess Cassandra had been gifted the capacity for prophecy by Apollo but also cursed to have nobody believe them and she warned of doom if the horse was dragged into the city. Laocoon, a priest of Poseidon (here following Virgil’s Aeneid so specifically a Roman version), separately warned about the horse, throwing a spear against the horse to show it rang hollow. Poseidon, clearly favoring the Greeks, sent two sea serpents to devour Laocoon and his two sons, alarming the Trojans but also causing them to disregard his warnings. The wooden horse was dragged into the gates and the city’s fate was sealed. From there, ten years after the war had began, Troy’s fate was sealed and the city would be put to the torch by the marauding invaders. (The Trojan War cycle does not end here however and many works of literature were devoted to the return journeys of various figures. Next follows a plot summary of the three most notable: Aeschylus’s Oresteia, Homer’s Odyssey, and Virgil’s Aeneid.)

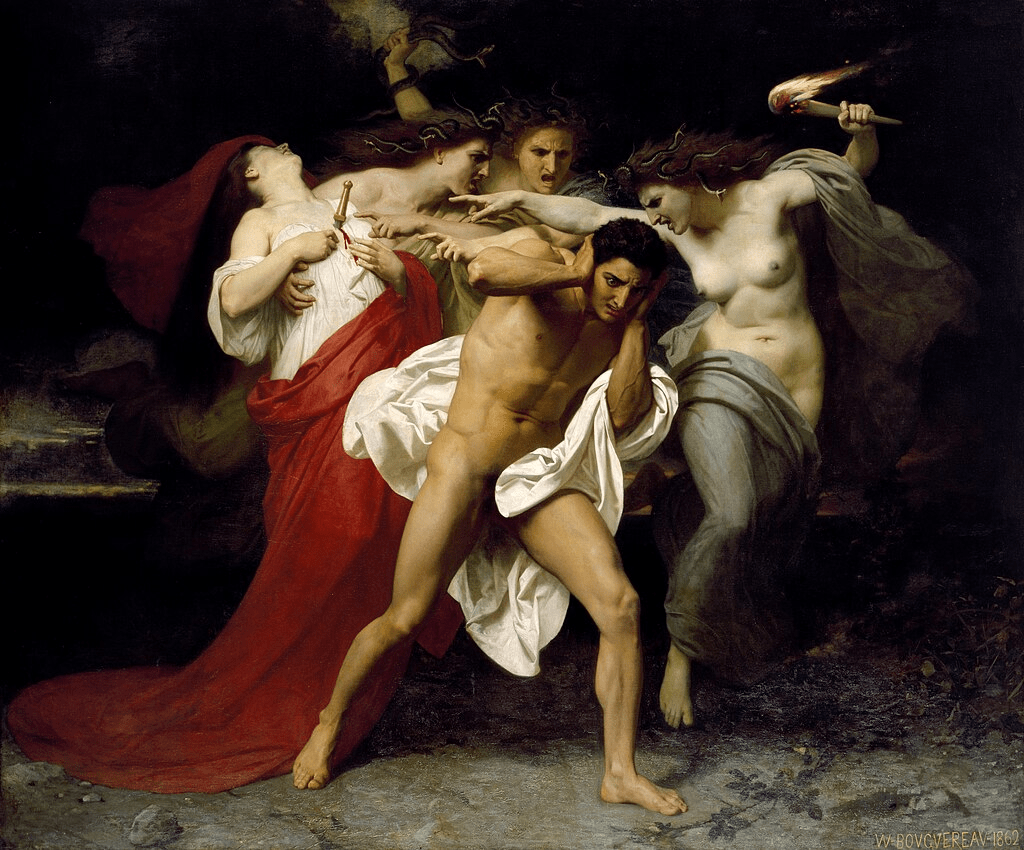

Orestes Pursued by the Furies by French academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau, which he created in 1862. Orestes is in the front with the three snake-haired Furies behind him carrying the slain body of his mother Clytemnestra. Greek literature such as the Oresteia does not actually specify a number of or names of the Furies, which are innovations of the Roman period popularized through Virgil and his late medieval fanboy Dante Alighieri. But the idea that there were three named Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone is pretty standard in modern portrayals now. Bouguereau’s work covering themes from classical mythology is excellent and he represents very well the academic establishment of French painting in that period. If he seems overshadowed in art history, it is perhaps also because his rigid traditional styles were some of the exact sorts of materials that the younger generation, the emerging impressionists, were pushing back against.

(The Oresteia is a series of three plays by Aeschylus, written in the 400s BC. The plays fall within the Greek theater drama of tragedy and tell the story of the fall of the House of Atreus, the dynasty in Mycenae that includes Agamemnon. While the Oresteia has come to be sort of the definitive telling of this story, the idea of Agamemnon’s murder is much earlier and even gets recounted by the ghost of Agamemnon in the Odyssey when Odysseus encounters him in the underworld.) As news spread that Troy was burning, the families of those who had been gone for ten years began to anticipate their returns. Clytemnestra, the queen of Mycenae and wife of Agamemnon, had been resentful of her husband ever since he had tried to sacrifice their daughter Iphigenia (in the play’s version of the story, she had not been saved by Artemis). As Agamemnon rode in victory parade through Mycenae, the presence in his chariot of the Trojan princess and prophetess Cassandra as a new concubine made her extremely angry. After the king and his concubine had settled within the palace, Clytemnestra exacted a murder plan and had Agamemnon stabbed in his bathtub with Cassandra being disposed of not long after. Cassandra then invited her former exiled lover Aegisthus to rule with her. This snubbed the intended heir Orestes who some years later returned unrecognized to the palace to have vengeance against his mother on behalf of his father. He first murdered Aegisthus, prompting Clytemnestra to rush into the room where she was murdered as well. This incensed the wrath of the Furies, primal deities who punished the breakers of oaths and kinslayers, generally depicted as women with wings and snakes for hair who attacked their victims with whips and torches. Apollo protected Orestes for a time, allowing him to flee them for a time but soon when the Furies got to him, it was only by the intervention of Athena that he was delivered. She prescribed a trial at the Areopagus of Athens where a jury of peers would determine if Orestes would be punished. The vote was tied and Athena cast the tiebreaker, determining he was to be left alone. Finally, she ruled that such punishments were to be decided by similar trials in the future, thus inventing the legal system. (It should be noted that Aeschylus was an Athenian playwright at the height of Athenian power and democracy, writing for an audience which would have been steeped in and celebrative of democratic values. If the conclusion of the story feels odd, it is because it is an expression of the values of the society at the time, but isn’t it kind of interesting that an origin story related to Athenian democracy is added to the Trojan War cycle?)

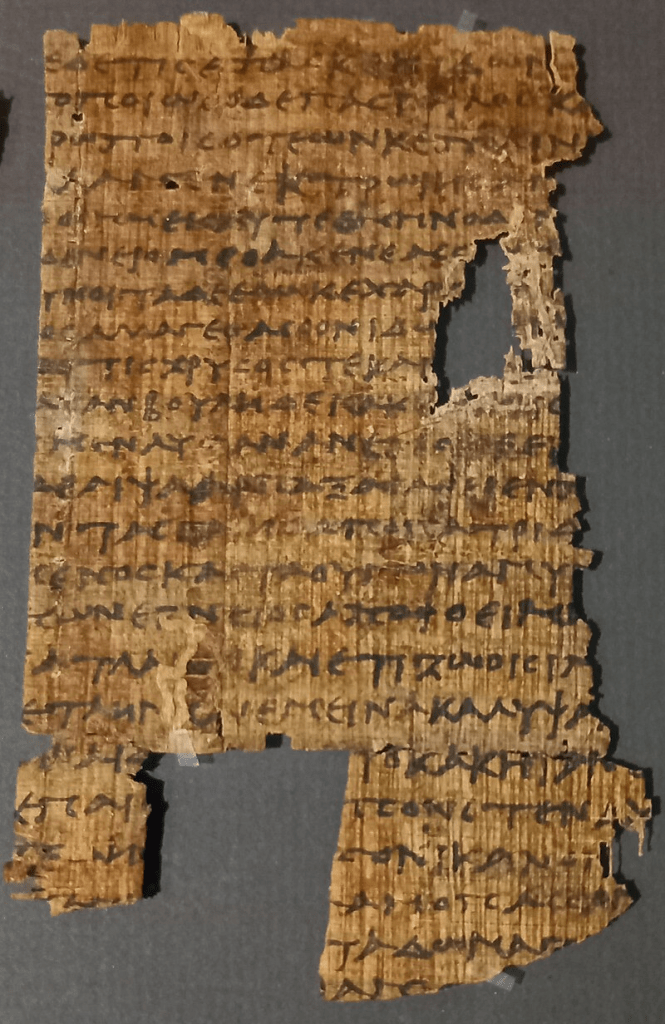

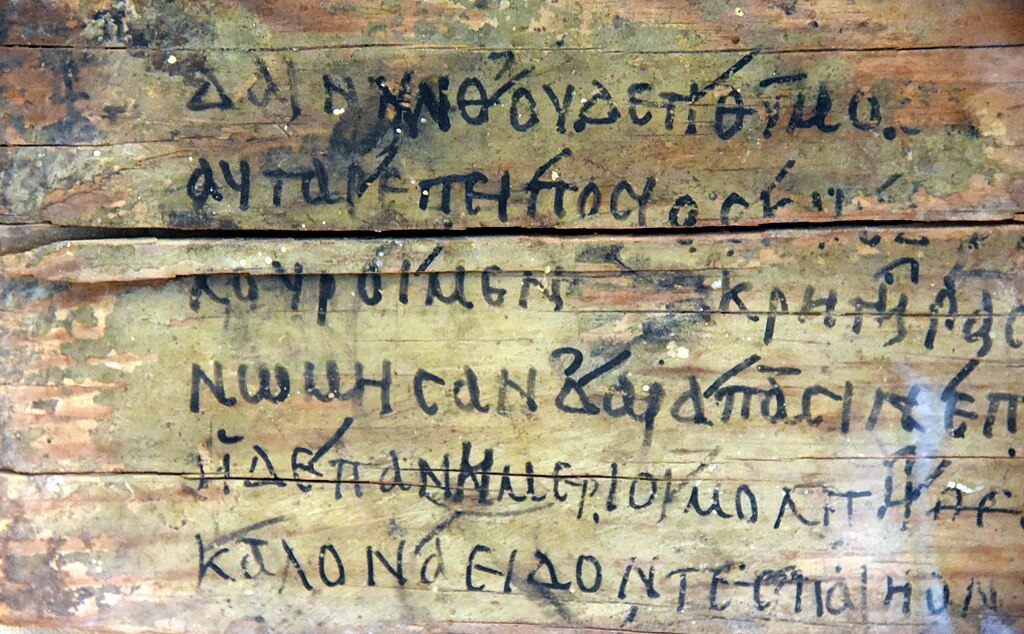

This is the oldest known fragment of the Odyssey, dating from the 200s BC in Ptolemaic Egypt.

(The Odyssey is the second great epic poem attributed to Homer, recounting the drama of the return of Odysseus to his home in Ithaca and the struggles of his wife Penelope and son Telemachus there. It dates to around the 700s BC and is considered marginally younger than the Iliad.) If Agamemnon’s story is one of an easy return followed by terrible reception, that of Odysseus was the opposite. At the opening of the Odyssey, it is about 10 years since the war ended and Telemachus is nearly 20, having never known his father. The palatial house at Ithaca is occupied by 108 rambunctious suitors who are all trying for the hand of Penelope to try to gain Odysseus’s wealth and kingdom. Meanwhile, Odysseus is released from the magical isle of Ogygia where the goddess Calypso has held him as a lover for seven years. His raft washes up on the utopian Phaeacian (an imaginary people) island of Scheria where he is rescued by the princess Nausicaa and taken to the court of the king Alcinous. There, Odysseus tells them a dramatic tale about how he left Troy… After withdrawing from the war, the hero and his men raided the Cicones in Thrace for more booty but then were driven off-course by a storm, crashing in the land of the lotus-eaters who were entranced by the fruit of the lotus plant to never want anything but to eat more of it. Some of Odysseus’s men tried it and subsequently had to be dragged back to the ships by force. The crew’s next landing was in the land of the one-eyed giants called Cyclopes where the men entered a cave filled with all the food they could want. But then the Cyclops Polyphemus returns with a flock of sheep and closes the door by moving a massive boulder in front of the cave entrance. He then eats two of the men when they make contact inside the cave, after Odysseus says that his name is “Nobody,” a tricky way to keep the giant from summoning help in the future. Odysseus sharpened a massive wooden stake and plunged it into Polyphemus’s eye while he slept, blinding him. Polyphemus called out that Nobody was hurting him, which the other Cyclopes found fairly silly and left, but then in care of his sheep Polyphemus needed to open his cave and Odysseus and his men escaped by clinging to the bottom of the sheep. As Odysseus escaped, he made the mistake of yelling boastfully back to Polyphemus, identifying himself, which allowed the Cyclops to pray to his father Poseidon to incense his wrath against the sailors. The sailors next came to the isle of the wind god Aeolus, who gave Odysseus a bag of winds and sent him on his way. But as the fleet neared Ithaca, some of the commander’s men decided to open it and released a dramatic windstorm that blew the ships back in the opposite direction where Aeolus refused to help them again. The next stop was in the land of the man-eating giants known as Laestrygonians who destroyed all the ships but one. Odysseus and his remaining ship landed on the isle of Aeaea, where the sorceress goddess Circe lived. Circe turned many of Odysseus’s men into pigs but he was protected from her magic with a magic drug given to him by Hermes, the messenger god. Circe then fell for Odysseus and they eloped for a year before he and his crew longed for home and set off again, taking advice from her on how to get home. Odysseus went to the underworld at the western edge of the Earth where he communed with the dead by offering blood to their ghosts, learning from the blind seer Tiresias that his crew would be doomed if they made the mistake of eating the sacred cattle of the sun god Helios. He also communicated with other dead figures from the Trojan War, including the murdered Agamemnon. The next phase of the journey took them past the Sirens, whose beautiful singing unavoidably enticed those who heard it. Odysseus’s men plugged their ears with wax while he was tied to the mast so he could hear it without getting away. Then the sailors passed through a narrow strait tormented by Scylla (a six-headed monster) and Charybdis (a huge whirlpool) where Odysseus made the decision to sail closer to the former who would eat only six of his men rather than the latter who would destroy the whole ship. They arrived at the isle where Helios’s cattle were and ran out of food, causing Odysseus’s men to make the fatal mistake of slaughtering the cattle while Odysseus was away praying. In the ensuing storm sent down by Zeus on Helios’s behalf, the crew suffered a shipwreck and all died except Odysseus who washed up on Calypso’s isle, bringing the narrative back to where the Odyssey started… Impressed by Odysseus’s harrowing tale, the Phaeacians make arrangements to send him home by their magical self-sailing ships (then having their lands encased in a mountain in punishment by Poseidon, which is why you can’t visit their utopian isle today). Odysseus comes back to his house disguised as a beggar, making contact with Telemachus and scheming with Athena to kill the suitors who are occupying the place and causing trouble. Penelope had attempted to put off choosing one to marry by telling them that she would first knit a burial shroud for her aging father-in-law Laertes, but each night picking apart the stitching so she would not finish. This had been discovered and now she is increasingly pressed to make a choice, so she proposes a challenge that she will marry any who can string Odysseus’s intensely difficult bow and shoot an arrow through 12 axe heads. Only the lowly beggar could do this, before revealing himself to be Odysseus and slaughtering the suitors with Telemachus. Thus Odysseus takes back control of his house and kingdom. (The Odyssey is an incredible read and I fully endorse the Emily Wilson translation into English.)

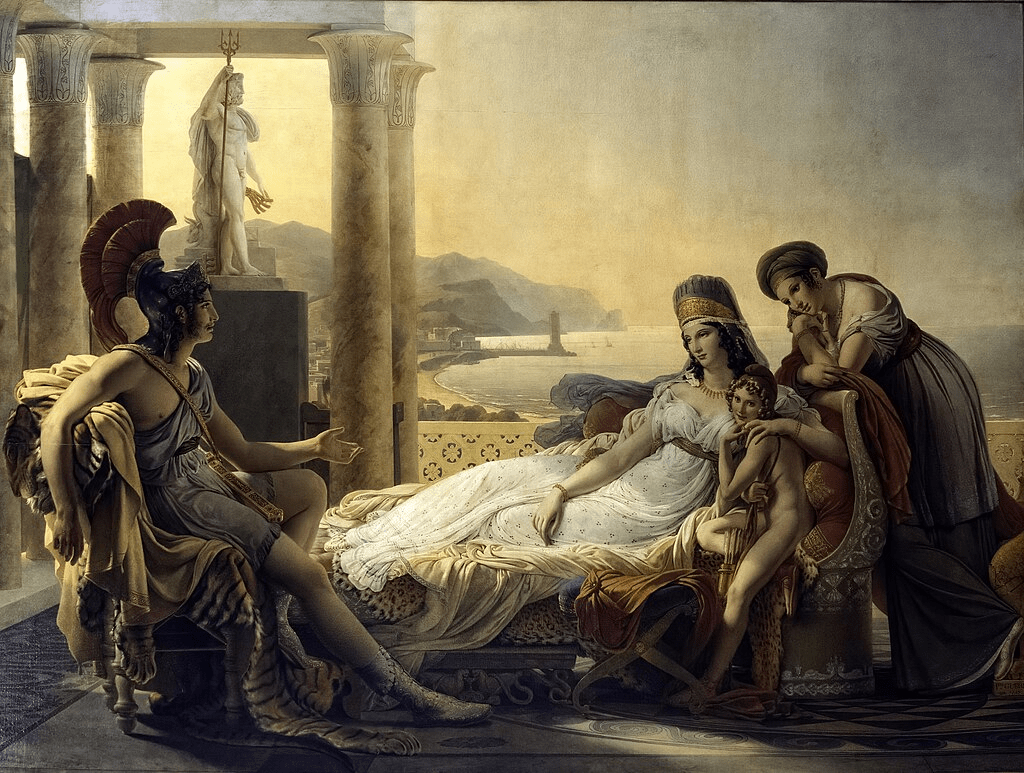

Aeneas recounting the story of the Trojan War to Queen Dido of Carthage in an 1815 painting by French painter Pierre-Narcisse Guérin. This scene from the Aeneid has been frequently depicted in art. Unfortunately, on the off-chance both figures were historical, they would have lived centuries apart. The Trojan War, if it happened, was likely in the 1200s or 1100s BC while Carthage was established in the 800s BC. Being that Dido is one of the cuter leaders in Civilization VI, I need not be jealous of Aeneas since he wasn’t dating her either.

(The Aeneid is different from most of the other major works thus far in that it was composed in Latin and specifically written by the poet Virgil within the orbit of the Roman emperor Augustus, whose regime it operated as propaganda for, completed in 19 BC. It imitates the dactylic hexameter of Homer and expands on a virtuous Trojan demigod hero, Aeneas, whom earlier legends had already associated with settling in Etruria, a civilization and region of Iron Age Italy, after the war, turning him into a progenitor of the Romans. The story abridged here is the Aeneid‘s version with the Anglicized Latin versions of character and place names used.) For the Trojans who survived the war, the journeys that followed were not homecomings but instead searches for new places to take refuge. The most famous of these journeys was that of Aeneas, who, it was foretold, would go on to found a noble people in Italy. As Troy burned, he sought out and rescued his wife Creusa, his son Ascanius, and his aging father Anchises who had to be carried out on his shoulders. Creusa got lost on the way and, going back into the city, Aeneas only found her ghost who told him that he must continue to Italy where he would find kingship and a new wife. With the protection of his mother Venus (the Latin name of Aphrodite), he constructed a fleet of ships along with remaining Trojan survivors and set out to establish a colony. He hopped from island to island in the Aegean, trying different potential places, in most of which he encountered a prophecy encouraging his continuation towards destiny in Italy. At Buthrotum, he found a colony of other Trojan refugees, who were attempting to replicate their old city. There he met Hector’s widow Andromache as well as a son of Priam named Helenus with the gift of prophecy, which he used to once again repeat the Italy bit. But he also suggested that Aeneas should seek out a prophetess known as the Sibyl of Cumae once there. Continuing towards Sicily, Aeneas was caught in the great whirlpool Charybdis and thrust out to sea, landing in the isle of the Cyclopes sometime after Ulysses (Latinized Odysseus) had been there, even picking up one of his abandoned crew members. Leaving this land, Aeneas washed up at Carthage in North Africa, following a storm sent by the angry goddess Juno (the Anglicized Latin name of Hera) due to her anger against the Trojans. Carthage was one of Juno’s favorite cities and it had been founded by a Phoenician queen named Dido who had fled Tyre in modern Lebanon. Venus decided to excite love between Aeneas and Dido and sent Cupid (the Anglicized Latin name for the god who personified erotic passion, called Eros by the Greeks) to make them fall for each other. Aeneas told Dido of his journey in her court and the two promptly had a sort of debatable marriage ceremony. But afterwards, Mercury (the Anglicized Latin name of Hermes) came on behalf of Jupiter (the Anglicized Latin name of Zeus) to tell Aeneas that he still had to go off and pursue his destiny. When Aeneas announced his departure to Dido, she was emotionally distraught and stabbed herself to death on a funeral pyre, declaring that there would be endless strife between their two peoples (thus foreshadowing the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage). Aeneas then went off to Sicily and hosted some funeral games for his father. Then, having found the Sibyl of Cumae, she guided him in a descent into the underworld where he saw its different regions (unlike in the shadowy Homeric depiction, by the Roman imperial period the underworld had distinct regions for those who’d been judged differently) and he sought out Anchises, located in the paradisical realm of Elysium, who showed him the River Lethe from which the virtuous could drink to forget their old lives and be born again. Anchises told his son of his immense destiny to found Rome, which would come to rule the world. Gesturing to the spirits of the Lethe, he pointed out those who would become various famous Romans, including Romulus and Julius Caesar. Leaving the underworld and his father, Aeneas continued to Italy, arriving in the region of Latium. There, he found the region under the sway of a ruler named Turnus of the Rutuli, whom Aeneas made alliances with neighboring peoples to fight in a great war, which ended in the Trojan hero winning against Turnus in single combat.

Clashing Kingdoms in the Age of Bronze

Woo. Hopefully now you feel caught up with the mythology buffs. As you can see, the Trojan War myth cycle is not only extremely extensive but overlaid with a multitude of extremely diverse threads, Greek and Roman, realistic and fantastical, popular and obscure. The genres which have composed the story include epic heroic poetry, tragic plays, hero narratives, works of history, religious framings, and even explicit propaganda for various later states. When discussing “the history of the Trojan War,” there are two separate subjects contained therein: 1) what historical event underlies the myths if there is one and 2) how the story developed over time to become the version we know and under what historical forces. These questions are deeply interrelated but must also be treated separately as appropriate. In the next section, I will deal with the world that the Trojan War would have taken place in and whether there is a place for it there. But first, we need to talk about Heinrich Schliemann.

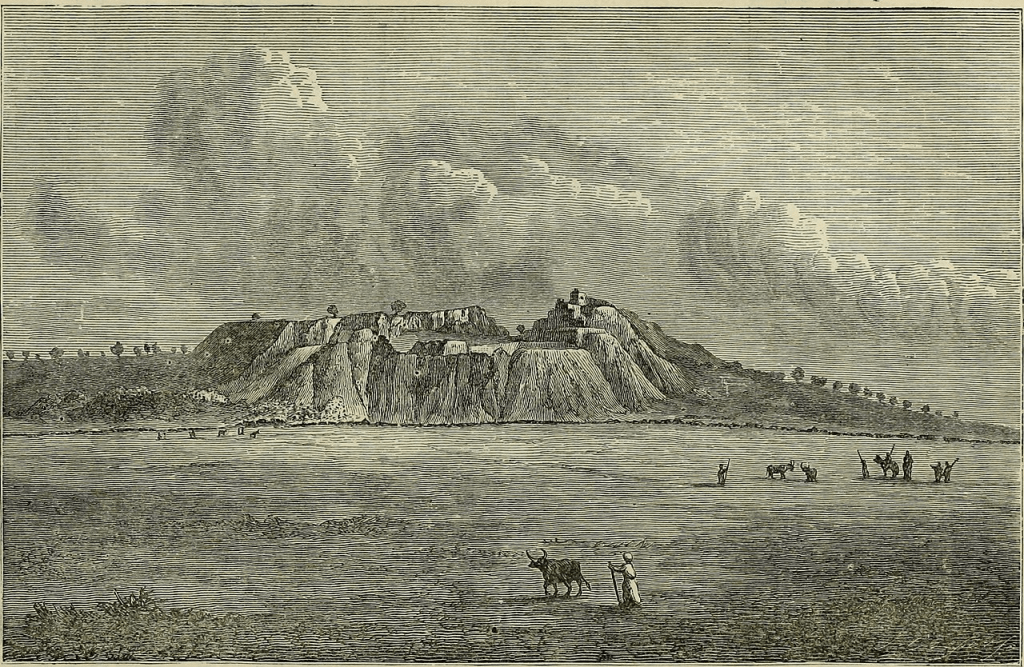

Hisarlık, the archaeological site of historical Troy, as depicted in the 1880 publication of Heinrich Schliemann which he humbly titled Ilios: The City and Country of the Trojans: the Results of Researches and Discoveries on the Site of Troy and Throughout the Troad in the Years 1871-72-73-78-79: Including an Autobiography of the Author. Yeah. At the top of the hill, you can see a huge trench where Schliemann excavated and dynamited his way into the depths of ancient Troy.

Heinrich Schliemann is perhaps one of the most notorious personalities in the history of archaeology. Born in the German Confederation in 1822, Schliemann was, according to his own (overly dramatized and often unreliable) autobiographical narrativization, so fascinated by the legends of the Trojan War that he vowed to someday find and excavate Troy at the age of 7. Though born not particularly wealthy, Schliemann managed a number of business ventures across a number of countries, moving at times to the Netherlands, Russia, and the USA. A multilingual eccentric, his rule was to write his diary in the language of whatever country he happened to be in at the time and apparently this successfully helped him to have geographically diverse ventures that made him fairly wealthy. Schliemann also had a knack for sensationalism, even writing a firsthand account of the San Francisco Fire of 1851, which he was not even present in the city for, having established a bank in California a few months later when he arrived but then leaving the state promptly when local investigations thought the speed at which he had raised money from the Gold Rush to be questionable. Whatever the case, an absolutely loaded and extremely weird Schliemann retired in 1868 at the age of 36 with the intention of dedicating his life to finding Troy. He had no archaeological experience or training.

Sophia Schliemann, Greek wife of the infamous Heinrich, wearing jewelry found during the excavation of Troy in 1873 as part of “Priam’s treasure.” This photo was taken in around 1874 after the treasures had been smuggled to Greece.

It’s an often-repeated story that before Schliemann, everyone thought Troy was entirely fictional. In researching this history, this does not seem like the case. The general area Troy would have been was already well-accepted and others had attempted to identify locations. The Greek historians that a lot of these philhellenes relied on tended to accept it as a true historical locale and settlements there by related names such as Troas remained prominent into the Roman period. On top of this, chronologies and timelines in the 1800s frequently make the assumption that Greek myths are rooted in historical fact and include mythical figures and events. No, I think that the idea that Schliemann proved to all the doubters that Troy was real stems mostly from his own self-aggrandizing presentation of it than anything else. Regardless, he did excavate the site. At the time, the modern site was part of the late Ottoman Empire, not far from the imperial capital of Constantinople. An Englishman by the name of Frank Calvert had purchased an ancient tell site called Hisarlık overlooking the Bosporus and done some preliminary excavations there, but nothing too extensive. Tells are archaeological sites where successive phases of human settlement on the same spot over a long period of time leads to layering and the formation of a sort of hill. This was already understood in early archaeology and Calvert recognized the site as one of these and believed it might be Troy, inviting Schliemann to check it out. Schliemann got to work in 1870, carving a massive trench through the site using large amounts of contracted local labor as well as sometimes dynamite. The Ottoman Empire agreed that he could carry out this process as long as historical artifacts were properly kept and displayed. Meanwhile, the unprofessionally organized excavation destroyed about as much as it found, leading to reconstruction problems to this day. In 1873, Schliemann found what he considered to be “Priam’s treasure,” a horde of gold and other precious artifacts in the tell. He believed he had finally found the layer of Homeric Troy. The next year, being a wealthy European adventurer of the 1800s, he smuggled the artifacts to Greece, from which they would eventually make their way to Germany, prompting trouble with Ottoman authorities, who nevertheless let him continue excavations.

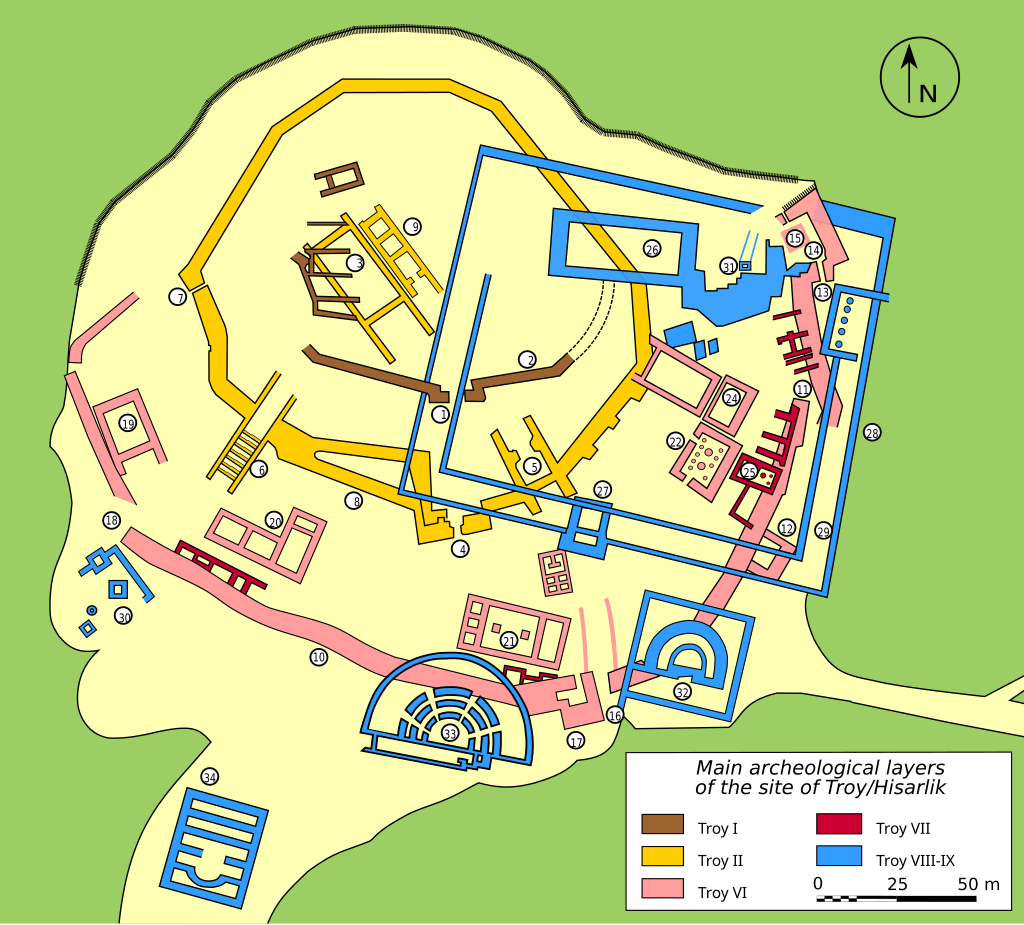

A schematic of the archaeological site of Troy with major features indicated by layer. This schematic is by Wikimedia contributor Bibi Saint-Pol.

Schliemann identified a number of layers and gave them Roman numeral names to discuss them historically. With radiometric dating having come about since, we now know that his dates are very off. In fact, “Priam’s treasures” date to between 2600 and 2400 BC, more than a millennium before any historical Priam would have lived. Schliemann had dynamited his way through Homeric Troy on the way to declaring an even older Bronze Age phase as the one. Regardless, his layers are useful for designating phases of the site as long as the dates are properly adjusted to modern understandings. Below is a chart of the layers of Troy and the approximate dates of those layers. Highlighted are the layers we actually today consider candidates for the Troy of the mythic cycle. The site was inhabited impressively from around the end of the Neolithic to well past the height of the Roman Empire. Dates are approximate and not exact and therefore reading more papers you will encounter occasional slight discrepancies.

| Troy 0 | 3600-3000 BC |

| Troy I | 3000-2550 BC |

| Troy II | 2500-2300 BC |

| Troy III | 2300-2200 BC |

| Troy IV | 2200-2000 BC |

| Troy V | 2000-1750 BC |

| Troy VI | 1750-1300 BC |

| Troy VIIa | 1300-1180 BC |

| Troy VIIb | 1180-950 BC |

| Troy VIII | 950-85 BC |

| Troy IX | 85 BC-500 AD |

The famous Lion Gate of Mycenae, also wonderfully representative of Mycenaean stonework. It was built late in the Bronze Age, around 1250 BC. This photo is by Wikimedia contributor Andy Hay.

Let us imagine ourselves in the Bronze Age and tell a new story of Troy, that which archaeology has built for us, starting with the time period associated with what Schliemann labeled Troy VI, between 1750 and 1300 BC. Greece was in transition as the Mycenaean civilization arose. (We get the word “Mycenaean” from none other than Heinrich Schliemann! After excavating Troy, he worked on tombs at the site of Mycenae in Greece and called this phase of Greek material culture after what he found there.) Unlike the earlier Minoan civilization of Crete, the epicenter of the Mycenaean phenomenon was the Greek mainland. As the culture matured, around 100 major settlements sprung up, which presumably acted as different city-states. A key relationship in Mycenaean centers was between the fortified “palaces” and the villages around them. Like anywhere in the ancient world, the primary occupation of most people was agriculture, farming the same animals and plants that had been domesticated in the Near Eastern Neolithic. Villagers would carry out these tasks while in the palace complexes, specialized craftsmen would turn raw materials into finished goods. The palaces also had ample storage space for food and other resources and likely held political power, though exactly what political organization looked like in this period is a little hard to say. In a lot of ways, the large house of Odysseus and Penelope in the Odyssey evokes Mycenaean palaces, employing many specialists and holding wealth and storage within Ithaca but also being somewhat open for people to just come in and out of as an active part of the local economy. Mycenaean palaces and fortifications were sometimes built with ashlar blocks but were often also built with colossal barely worked stones that are sometimes called “Cyclopean.” (This comes from an account by 100s AD Greek historian Pausanias who relates a tradition that the walls in Mycenae were built by Cyclopes. Many modern commentators frame this as the classical Greeks not being able to explain how humans could have made these structures but this interpretation is pretty silly on its face as the stones Pausanias was referring to are not especially grand in size compared to other common examples of Greek masonry. It simply represents a folk tradition related to this particular site, its antiquity and its somewhat rough masonry in areas. That should save you a few dumb pseudohistory rabbitholes online.) Mycenaean cities engaged in trade with one another and with the wider Mediterranean world, spreading their culture into the Aegean islands and supplanting the earlier Minoan and Cycladic cultures there.

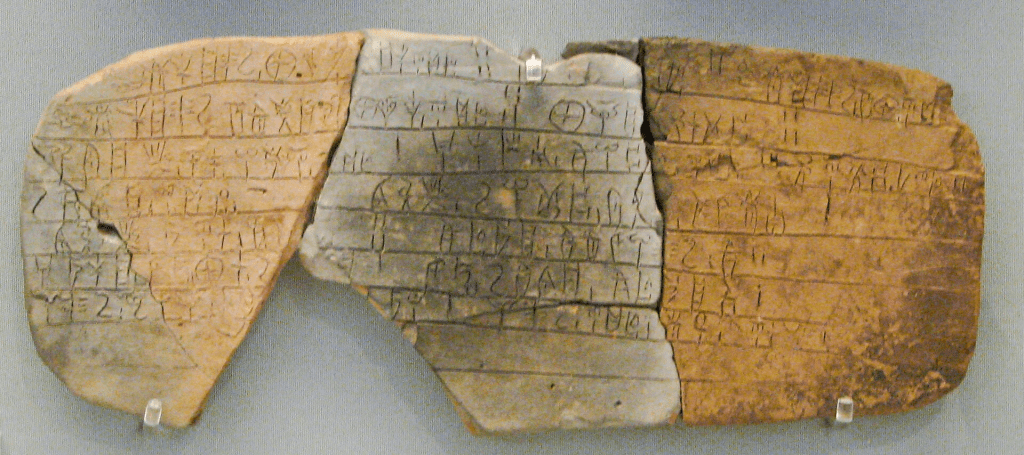

A sample of Linear B writing from the Mycenaean settlement at Pylos, shared to Flickr by Sharon Mollerus. This particular text is of bookkeeping nature, noting the distribution of cattle, pig, and deer hides to specialists who will make products such as shoes and saddles.

Of note to our discussion is also Mycenaean writing, which takes the form of a script called Linear B. Writing in the Aegean began with the several scripts of the earlier Minoan civilization, including Cretan hieroglyphs and Linear A, none of which have been deciphered in modern times. The latter though was widely used across Crete by around 1500 BC when it was adapted on the Greek mainland into Linear B. About 70% or so of Linear A’s approximately 90 known characters wound up in the new Mycenaean script but with probably new applications (as Linear B’s decipherment has not really led to the same in Linear A). In total, there are about 5,000 examples of Linear B text known today, which have become readable since a breakthrough by British architect Michael Ventris in 1952, who demonstrated that the writing system encoded an early form of Greek (though it’s believed that the phonetic values of the characters don’t match spoken language exactly; the writing system is syllabic but Greek is not a language that can be easily cleanly split that way; as such, it is imprecise, like if you tried to phonetically approximate English with Chinese characters). The bulk of this corpus is relatively transitory administrative documents pressed into clay tablets (like similar contemporary objects in Mesopotamia) which through accidents like fiery destruction events became hardened and preserved in collapse layers. As such, they tend to give a very economic view of their societies. A lot of these are effectively inventory lists, tallying up stocks of food, livestock, raw materials, manufactured goods, etc. stored somewhere or being sent elsewhere. Sometimes the tallied resources are human, such as laborers, soldiers, or the rowers of ships being tasked to some place for an activity. These documents support the idea that Mycenaean city-states were what archaeologists and historians of the ancient Eastern Mediterranean call “palace economies,” centralized planned systems where the elites within the palace complex took in and redistributed community resources. Such systems were actually common throughout the Near East and probably with the Minoans before as well, though market systems existed to varying degrees in relation to this from polity to polity, albeit without standardized currencies. Another item of interest in our discussion of mythology is that through Linear B we can see early forms of the Greek gods, though often with very different characteristics. In the corpus of texts from Pylos for instance, Po-se-da-o, or Poseidon as we know him, seems to have been the major deity with Di-we (Zeus) taking a backseat, which may have been a larger pattern as indicated by the relative frequency of those gods in the textual corpus.

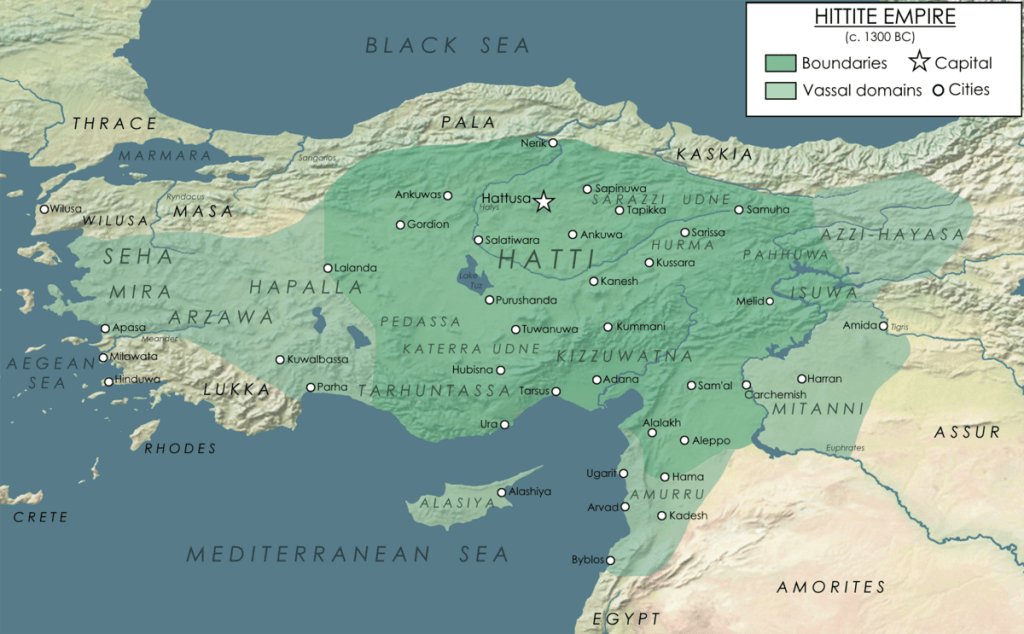

The Hittite Empire around 1300 BC in a map by Wikimedia contributor Ennomus. Troy is marked on this map as Wilusa, an ancient name which most scholars agree refers to the site.

To the east of both Mycenaean Greece and Troy VI, another empire loomed over most of Anatolia: that of the Hittites. “Hittite” is, like “Mycenaean,” primarily a term of modern scholarship, though it derives from ancient terminology. The biblical “Hittites” are a group of people mentioned as living in Canaan (the Levant) in several books of the Hebrew Bible, texts which date from the Iron Age and later in the first millennium BC. The identity of these biblical people in relation to archaeology remains contentious but from the early 1900s onwards, archaeologists became aware of a state known as “Hatti” in central Anatolia that interacted extensively with other powers like Assyria and Egypt and which left an archaeological record of great fortified cities of its own. When we refer to the Hittites today generally, we are now referring to this civilization and state. The Hittites were, like the Mycenaeans, an Indo-European-speaking people but, unlike them, of the now-extinct Anatolian branch of this larger language family. Around the middle of the 1600s BC, they established a kingdom centered around the capital city of Ḫattuša, located in what is now the north-central part of modern Turkey. Within the next century, a large citadel was constructed at this site and urban planning began to define the site recognizably. The Hittite realm was multicultural, multilingual, and multireligious with many languages attested in scripts extensively, including Hittite itself, another local non-Indo-European language confusingly called Hattic, a different Anatolian language called Luwian, and the Mesopotamian Semitic language known as Akkadian which was used as a lingua franca throughout the Late Bronze Age Near East. It is this rich literary legacy, internal and external, that allows us to piece together much of Hittite political history in addition to the archaeological record. As the Hittite Empire began to subdue smaller earlier states in Anatolia around it, its major competitors became Assyria in what is now northern Iraq and Mitanni in what is now Syria. The first great Hittite conqueror was Ḫattušili I who carved out a kingdom that stretched from the Mediterranean in the south to the Black Sea in the north, from the Aegean in the west to the northern reaches of Mesopotamia in the east, ruling from around 1650 to around 1620 BC (Hittite historical records are timed with our calendar by radiometric dating of material evidence and so are approximate equivalents, not exact ones, even when recorded events exist; I will largely opt for a reconstruction called the “middle chronology” here). His successor Mursili I, ruling around 1620 to 1590 BC, took this expansion a step further and campaigned into Mesopotamia as far as Babylon, sacking the city in 1595 BC, ending the Old Babylonian Empire and the dynasty established around two centuries before by the famous Hammurabi. The Hittites did not hold this land so far afield and so the reasons for this impressive invasion are somewhat unclear. After 1500 BC, the empire weakened and contracted and records are scant in the following century and a half. But then another great conquering king arose who would take it to new heights in the form of the difficult-to-pronounce-properly Šuppiluliuma I, who reigned from around 1350 to 1322 BC. He retook lost lands and pressed the empire southwards into the Levant, taking much of what is modern Syria and Lebanon. This put the empire into a collision course with the New Kingdom of Egypt and the two great powers would jostle over this region on and off for the rest of the Bronze Age.

Of interest to our discussion is how the Hittites recorded the world to the west of them, which would have included the Mycenaeans and Trojans. Within Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the Greeks are generally referred to collectively as the Achaeans, a term that later Greek authors did not use for themselves. As scholars began to read Hittite records a little over a century ago, they were delighted to find that the Mycenaeans were referred to there as Ahhiyawa, seemingly confirming that the Homeric label represented an ancient name from the Late Bronze Age for the Mycenaean civilization. (This is further supported by the related Egyptian term for the Mycenaeans, Ekwesh.) These Ahhiyawa are often mentioned as adversaries in conflict with Hittite vassals and tributaries in western Anatolia as well as in the role of trade partners. In addition to this, the Hittite geographical term which has captured the most modern attention is that of Wilusa, a city to the west. Around the mid-1400s BC (the chronology is especially hazy here), a number of states in western Anatolia joined in the Assuwa Revolt, including Wilusa, though the revolt seems to have been short-lived and unsuccessful and within the next century, when Wilusa is in the historical record again, it was a very loyal vassal. For some excited readers, there is probably anticipation that I will reveal Wilusa as the historical Troy, as this is a common part of popular and academic media discussing the historical basis of the Trojan War. The argument is largely predicated on, among other things, that Wilusa is etymologically related to Ilios/Ilion, another Greek name used for Troy in classical sources. This appears to be accepted by the majority of relevant experts but is also not consensus. I will largely treat it as the case for the rest of this article but for the sake of interest will briefly state that one major source of doubt for dissenters is that within textual descriptions, some interpretations think Wilusa is implied to be closer than other vassal states, which would be difficult if it were on the far western edge of Anatolia where Schliemann and Homer’s Troy is. Whether or not Wilusa is Troy does not change what we know about the archaeology from the site of Troy itself.

The walls and gate of Troy VI, shared by Wikivoyage user Bgabel. Troy had some of the most significant fortifications in Bronze Age Anatolia.

Knowing about the surrounding civilizations on either side of it, let’s turn back to Troy VI. This phase of the Trojan archaeological record seems to represent the city at its zenith. The city consisted of two main portions, somewhat like the cities of the Mycenaeans: a fortified citadel and an unfortified lower city. The latter was composed of scattered houses where poorer and less specialized members of society would have lived, probably largely working in agriculture. The citadel, however, was probably the most significant fortified center in the region, commanding effective power over a hefty portion of northwestern Anatolia. Constructed upon an acropolis, its walls were around 550 meters in length with bases between 4 and 5 meters thick. Several large houses were built within the citadel, some raised on terraces, demonstrating great earthworks in the process of construction. The wall itself was reinforced with several towers which might provide defensive positions against attackers. Even outside of mythology, Troy was as close as you could get to an unassailable city and the monumentality of its construction demonstrates that the elites who ruled over it could command colossal labor forces. It is difficult to say for sure what language the inhabitants spoke but it could very well have been an Anatolian Indo-European language, related to the likes of Hittite, Luwian, and Lydian, though of course Mycenaean Greek may also have been used there. Frustratingly, though, the actual archaeological site of Troy VI has not actually yielded any written evidence. It also does not seem to have been particularly important in trade with modest grave goods and few imports from beyond the Aegean. And then around 1300 BC, the city saw destruction from a great earthquake which was followed by fire. What followed, as inhabitants resettled in the new phase of Troy VIIb, was a period where Troy continued to exist but at a smaller scale than before. The lower city faded as new houses were built largely just within the citadel.

A depiction of soldiers from pottery found at Mycenae dating to around 1200 BC. Like most foot soldiers in the Iliad, the soldiers here carry spear and shield as primary weapons with highly decorative armor.

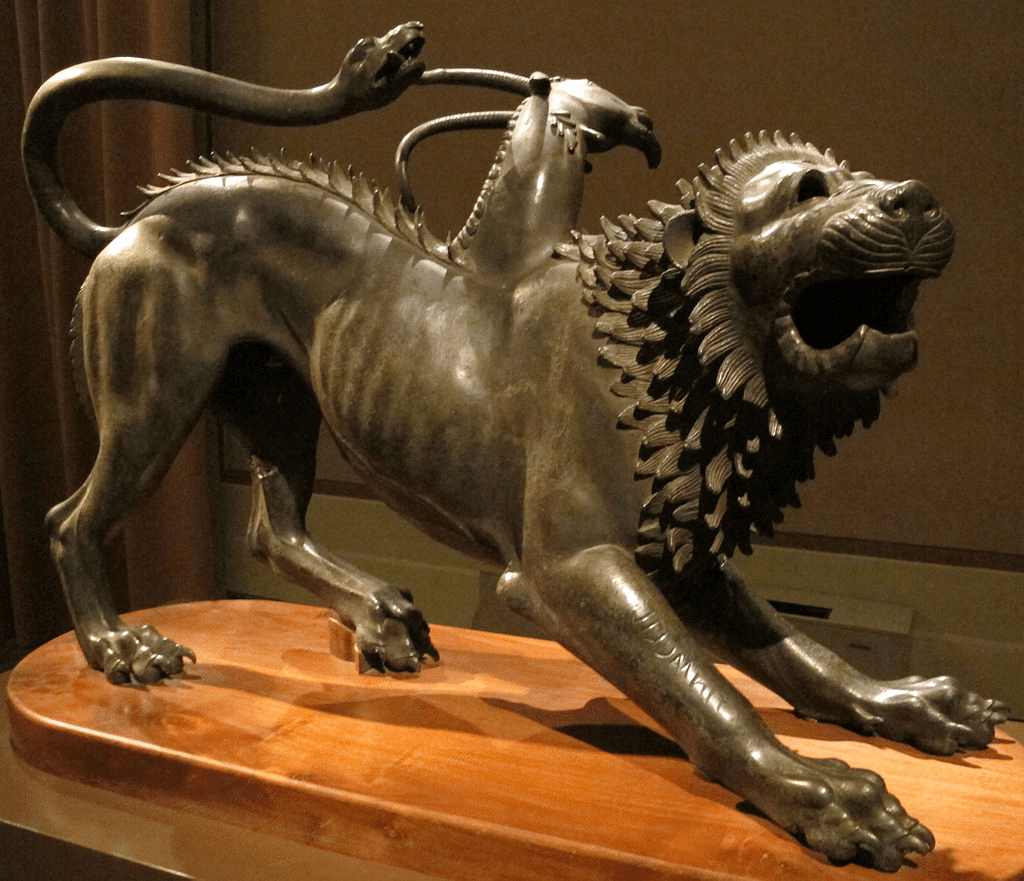

A major aspect of any discussion of how the Trojan War cycle in mythology relates to a historical basis is the question of how much Homer’s portrayal of conflict in the Late Bronze Age reflects actual dynamics of the Late Bronze Age versus a projected reality based on Homer’s period and the intervening centuries. The consensus seems to be that both of these are mixed in the final result and the sort of anachronistic mélange of characteristics draws from many voices across centuries. The weapons and armor of heroes in the Iliad seems often to carry Mycenaean echoes, such as the square tower shield carried by Ajax, the fact that champions are often taxied to the field by chariot, and Odysseus’s boar-tusk helmet. Most of the major commanders seem to come from Mycenaean-period city centers, though with specifically notable heroes added, possibly fed in from other traditions. On the eastward side of the conflict, there appear to be echoes of ritual practice native to Anatolia, even sometimes in relation to Greek characters within the epic. For example, in Book VI, the Lycian (another region of Anatolia, aligned with Troy in the mythic cycle) soldier Glaucus and the Greek Patroclus (remember, friend or boyfriend of Achilles) bond over family history and decide not to fight. Glaucus tells a tale of his grandfather Bellerophon who slays a monster known as the Chimera in what has been proposed over in the field of Indo-European studies to be a Hellenized version of the Luwian myth in which the sky god Tarḫunz kills the dreaded serpent dragon Illuyanka (perhaps I will have to cover ancient Anatolian mythology another time). Within the same book, a religious festival by the Trojans dedicated to Athena seems to echo Anatolian native royal religious practice, overseen by the queen and a priestess in a deeply feminine-dominated ritual. Finally as well, when Patroclus is killed in Book 16, he is given a funeral and burial that echo aspects of Hittite burial mounds. It is fascinating that even in this foundational piece of Greek literature, there appear to be influences from the decidedly non-Greek cultures the text explores.

The clay tablet of the Alaksandu Treaty, as reconstructed at the Troy Museum, in a photo by Wikimedia contributor Dosseman. This treaty from around 1280 BC between the Hittite king Muwatalli II and a king of Wilusa known as Alaksandu reasserts apparently older agreements of friendship between the two states. The language is Hittite, written in the cuneiform writing system.

But why stop at cultural practices? Can individual figures from the Iliad be tied to otherwise identifiable historical personages? Two figures may have a presence in the historical record, though either is contentious and both rely on the idea that Wilusa is in fact Troy. The first is Paris, prince of Troy in the mythic cycle, or Alexander as some Greek sources call him. A single fragmentary document impressed onto a clay tablet dating to around 1280 BC records a treaty between the Hittite king Muwatalli II (reigned around 1295 to 1282 BC) and a king of Wilusa known as Alaksandu. The two monarchs reaffirm previous friendship treaties between the two states which apparently predate both of them. Of interest is that Alaksandu’s name is apparently Greek rather than Anatolian (and the earliest attestation of the name Alexander in the historical record at that) and also that he may be a usurper since while he is a successor to another king called Kukkunni who was also an ally of the Hittites, Muwatalli does not stress the usual connection of kinship that would normally be important for establishing the recognized royal authority of an ally. Was Alaksandu a usurper of the throne of Wilusa from Mycenaean origins? The record is too fragmentary to say. But the possibility that this historical figure would later become the mythical Paris of Troy remains.

The second potentially historically attested figure from the Trojan War cycle is far more dramatic. In the mythic cycle, King Priam of Troy was the father of Paris and the leader of the city during the conflict. But Piyamaradu was certainly no legitimate ruler of Wilusa, at least in the eyes of the Hittite Empire. Piyamaradu was a warlord active for at least 35 years who was a threat during the reigns of Muwatalli II (around 1295 to 1282 BC), Ḫattušili III (around 1275 to 1245 BC), and Tudḫaliya IV (around 1245 to 1215 BC). He is referred to both by multiple contemporary texts, including political correspondence about dealing with him, and later texts as a notable figure of recent history. He may have been an unseated king of Arzawa unseated by the Hittites or perhaps some governor on behalf of the Hittites who then rebelled but whatever the lacuna in the record, he was a menace to Hittite interests in Western Anatolia. He appears to have asked for the status of vassal to the empire and then got refused. Following this, he revolted and another western vassal king ruling over the Seha River region, Manapa-Tarhunta, was sent to deal with him. Archaeologists have a letter from Manapa-Tarhunta to the Hittite king that informed the imperial government that things were fine and Hittite troops sent to him were successful at reversing Piyamaradu’s gains. Next they would head towards Wilusa where Piyamaradu was being supported by the Ahhiyawa against the Hittites. Interestingly, a “king of Ahhiyawa” is referred to in this and other Hittite letters, suggesting at least an outwardly recognized authority within the Mycenaean world, though this doesn’t necessarily mean full political unity. Another of these letters is the Tawagalawa letter, named after a brother of the Ahhiyawan king who is mentioned in the letter (the fragments remaining contain the name of neither king involved in the letter exchange frustratingly), which was addressed by a Hittite king to an Ahhiyawan ruler around the same time as the previous letter. The letter scolds the Ahhiyawan king for supporting Piyamaradu’s attack on Wilusa but then takes a conciliatory tone and tries to ask him to support Hittite interests instead by helping to deal with the troublesome rebel. In this appeal, the Hittite king refers to the king of Ahhiyawa as a brother, which is usually just how rulers of the great powers of the Late Bronze Age Near East referred to each other, signifying a period of apparently significant Mycenaean distance power, especially since their ruler could apparently decide the fate of Piyamaradu and had influence over the area around Wilusa. Some have suggested that this conflict is the historical Trojan War. We don’t know what the response was, if there was one. A later letter called the Milawata letter (named after what is probably the Hittite name for the later Greek city of Miletus, today in ruins in western Turkey) from a Hittite king to an unclear western vassal around 1240 BC refers to Piyamaradu as a figure of the past. The letter once again brings up Wilusa, suggesting that a pretender to the throne of the city that the Hittite king favors should be handed over so that they can install him as ruler of the city. Clearly the Piramayadu drama left a lasting legacy on the geopolitics of the contentious region.

All of this drama happened around the time of or shortly after the destruction of Troy VI. It is difficult to tie the destruction layer itself to events written in the historical record, relating to Wilusa or any other named place. But neither of the fiery earthquake-induced end of Troy VI or the chaotic drama of western Hittite frontier territory in the 1200s BC marked the end of the Late Bronze Age world that Troy was a part of. Are there other later events that could be tied to the myths? Ancient Greek writings on the fall of Troy vary quite a bit, stating various dates between the 1300s and 1100s BC. But Eratosthenes’s 1183 BC I have seen as a particularly common date of choice in modern publications. It just so happens this particular date falls close to the destruction of Troy VIIa in the archaeological record. To explore this, we need to talk about a wider process: the Late Bronze Age collapse.

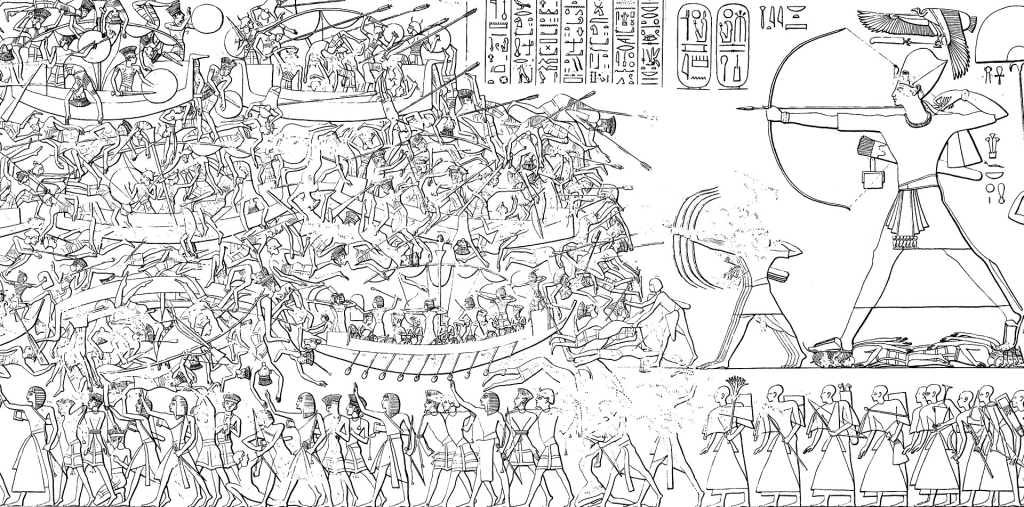

Part of the frieze from the mortuary temple of Ramesses III (ruled 1186 to 1155 BC) at Medinet Habu in Egypt. The scene depicts the pharaoh vanquishing a coalition of invaders at the Battle of the Delta around 1175 BC. The many listed invading peoples have become known to historians as “the Sea Peoples,” a name today which is emphatically associated with popular discourse on the Late Bronze Age collapse.

In the early 1100s BC, a series of destructive events humbled various urban and imperial civilizations throughout the Eastern Mediterranean world in what archaeologists have come to call the Late Bronze Age collapse. The most famous episode of this saga occurred in the great power that held up best, Egypt, in around 1175 BC. Ramesses III ruled as a New Kingdom pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty from 1186 to 1155 BC. His mortuary temple at Medinet Habu, located just across the Nile to the west of Luxor, records in spectacular scale a narrative of battle on the Nile Delta. The enemies of Egypt in this battle were a confederated group of various peoples who attacked by boats, coming across the sea, which prompted the French Egyptologist Emmanuel de Rougé to refer to them as “Sea Peoples” in a publication in 1855, a name which has stuck. The Sea Peoples in the Medinet Habu inscriptions include the Denyen, Peleset, Shekelesh, Sherden, Teresh, Tjekker, and Weshesh. Most of these people groups are only tentatively identified elsewhere, but others such as the Peleset, in their case as the biblically notable Philistines, seem clear. The Denyen may be connected to the Homeric term “Danaoi,” another word for the Greeks, though this is not universally accepted. Whatever the case, Ramesses’s description touts his successful repulsion of the Sea Peoples, driving them back into the sea and eliminating them. Following the death of Ramesses III (in an apparent conspiracy within his harem, recorded in the historical record and in modern CT scans of his mummy, which show his throat was slashed), however, Egyptian imperial territory severely contracted, with the empire abandoning all its holdings in the Levant. At least some of the Sea Peoples, specifically the Philistines, settled there, ruling their own cities in what is now southwestern Israel and the Gaza Strip for the first several centuries of the Iron Age. In the same period of time, writings from Ugarit in modern Syria called in vain for help against invaders from the sea, the Hittite Empire’s capital of Hattusa was destroyed violently, the Mycenaean cities abandoned their palaces and ceased their form of writing, and Troy VIIa was once again destroyed. For a long time, it was popular to ascribe the Late Bronze Age collapse to the Sea Peoples and argue that a wave of outside invaders just came in and toppled all the civilizations in the region, but this is probably putting too much weight on a small number of Egyptian texts and favoring easy but dramatic answers. More recent scholarship has come to see the Sea Peoples as symptomatic of larger collapse of interconnected systems and this discourse has increasingly drifted toward root causes in the climate as developments in the natural sciences have made these more visible after 150 years of archaeologists pondering the collapse.

Ancient regional climate reconstructions rely on putting together a multitude of lines of evidence to produce a good picture. These include botanical evidence such as pollen in soil deposition which demonstrates which climate-sensitive plants were in an area (with a category of plankton known as foraminifera taking a similar evidentiary role in marine contexts) as well as tree-ring data which can help measure the intensities of summer droughts. Other lines of evidence relate to soil deposition and reconstructions of the water table. For several decades, lines of evidence have pointed to sustained drought in the Eastern Mediterranean in the early 1100s BC, not to the extent that civilizations starved at all once but to the extent that over the course of several decades of repeated long dry summers, civilizational economies that had developed in better conditions became stressed and strained. The reasons for this appear to be shifts in the wind and current patterns of the North Atlantic Ocean, where moisture movement shifted northwards, making Northern Europe wetter and bringing less moisture into the Mediterranean Basin. All of the major urban civilizations of the region had agricultural economies and, what’s more, many of them were palace economies, command structures where authority was tied to the collection and redistribution of food. The theory of systems collapse goes that agricultural difficulties lowered the amounts of food that could be redistributed, lowering the providing power of the elites within these economies through famine and reduced trading capacity. At times this led to revolution but other times to large numbers of people moving from one place to another to seek new opportunities. This migration period manifested in the emergence of non-state armies that invaded lands and attempted to take spoils from the struggling states. These were the Sea Peoples who attacked Egypt and perhaps the destroyers of Ugarit, Hattusa, and Troy. The Late Bronze Age collapse did not end civilization in the region as some dramatized historical narratives like to say but it did push existing states near or to the breaking point, leaving the world afterwards to build up on new foundations. Even this explanation is simplified and the collapse played out differently in every area that it did, but this should provide context to look at the case of Troy and Mycenaean Greece. (I do not know where else to put this but it may be of interest that at least some of the Sea Peoples seem to have come from the Greek world. As mentioned, the Ekwesh or Denyen seem to be connected to Homer’s Achaeans or Danaans. But also, a body of evidence exists to support some Mycenaean origins of the Philistines. In pottery seriation, late Mycenaean pottery is considered identical to early Philistine pottery in the Levant. Genetic studies on Philistines show that while the majority of their ancestry was indigenous Canaanite, there was Aegean admixture around the collapse years. Finally, the Bible itself, in Amos 9:7, mentions a Philistine migration from Caphtor, a location traditionally translated as Crete.)

Anatolian Grey Ware from the Troy Museum in Turkey, photographed by Flickr user Carole Raddato. This was the type of pottery used at Troy both before and after the Late Bronze Age collapse. It is more similar to indigenous Anatolian than Mycenaean forms of pottery.

As mentioned, Troy VI had been destroyed before around 1300 BC or perhaps a little later in the 1200s BC, maybe or maybe not related to the Piyamaradu conflict. Troy VIIa was smaller, limited to the old citadel and probably built by survivors of the old tragedy. This settlement existed for around a century until the collapse years when it was set to flames again by unknown hands. In Troy’s remarkable resilience, it would be settled again, even showing material continuity in the early Iron Age when local forms of pottery would continue to be produced. Greeks had come to settle the area though and they would increasingly characterize it, perhaps telling stories about the reduced ancient city there and how their ancestors had vanquished it. The Hittite Empire would never totally recover and disappeared from the region forever here, though languages like Luwian maintained a presence. After the fall of Hattusa, their rule in Anatolia mostly collapsed, but a branch of the ruling dynasty continued to hold power in the city of Carchemish, a site which is today bisected by the border between Turkey and Syria. The Hittite rump state quickly broke down into a number of small kingdoms referred to as the Syro-Hittite states in what is now southeastern Turkey and northwestern Syria, which would exist until the 700s BC when they were absorbed into the growing empire of Assyria. If the Hittites referred to in the Iron Age texts of the Hebrew Bible really were the same people as the Hittites thus called by archaeologists, then it was probably these later southeastern decentralized Hittites.

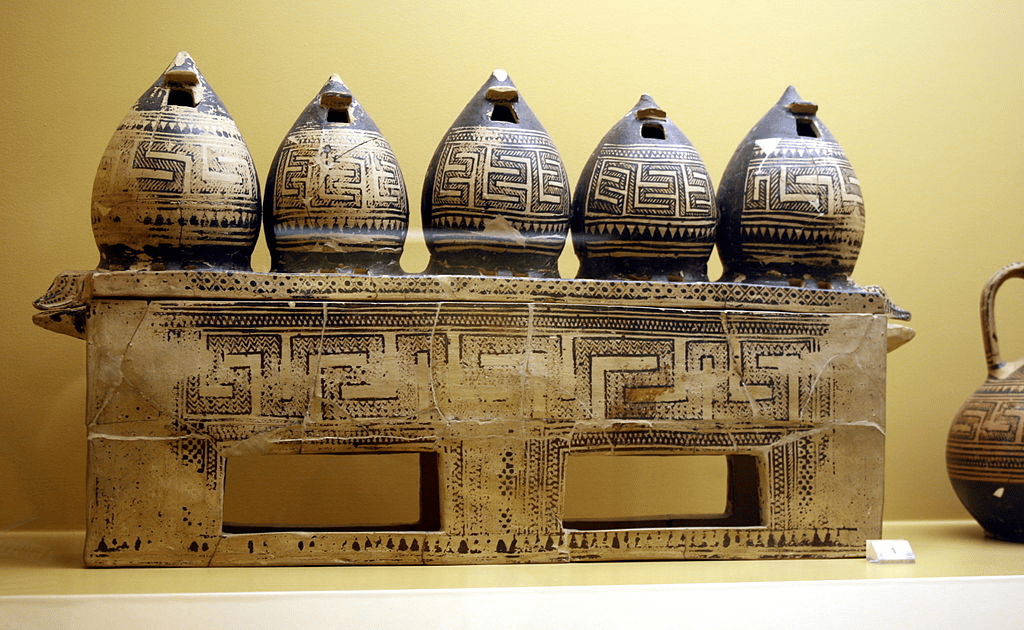

Geometric-style box from a cremation burial of an elite Greek woman around 850 BC in a photo taken by Wikimedia user G.dallorto at the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, Greece. How you gonna call it a Dark Age when things are this snazzy?