The mother Quetzalcoatlus leaps from the nesting ground to take to the air. She is a pterosaur, a flying reptile related to dinosaurs, and specifically one of the largest examples of one that will ever live, her 11-meter wingspan capable of striking fear in the minds of the small dinosaurs she often preys upon. This is a hunting outing. Her newly hatched young will need food and she herself has not eaten in some time. Before her in the sky, an especially bright star in the daylight horizon barely requires her attention.

Riding the updrafts of the warm air currents that can reduce the effort in lifting her gargantuan frame, she looks out over the amazing landscape of Late Cretaceous North America. Conifer forests interspersed with flowering plants support an amazing variety of life at its grandest. Immediately recognizable are the vast herds of Edmontosaurus numbering in the hundreds. These 12-meter-long duckbilled herbivores specialize in flowering plants, grinding their leaves in huge dental batteries and browsing the landscape clear before moving along. Passing over a patch of forest and then coming upon another opening, the Quetzalcoatlus looks down upon a brightly colored male Triceratops, his huge neck frill and formidable brow horns brandishing the gaudy displays of mating season. He is extremely fertile, at least it would appear, and a group of females mill about him cautiously with interest, while another male surges forward, ready to challenge him. A sort of hoppy dance ensues and the males will compete for attention in the form of display. But the mother Quetzalcoatlus will not stick around to see this show. Dinosaurs this large are not safe to hunt for a predator like herself. But this does not mean they are not preyed upon. On the way out of the area, she catches a glimpse over the tops of the trees of the alarming sight of a Tyrannosaurus rex moving in stealth, scanning the area for his own meal. T. rex is the most massive terrestrial predator to inhabit the planet and the mother knows better than to risk ground-hunting in his immediate vicinity. Among predators, there is a clear apex. The horizon’s star grows brighter and neither predator thinks much of it.

Some way along, she spies a herd of smaller Thescelosaurus, two-legged herbivores that max out at around 4 meters long. Immediately as she carries low over them, the herd begins to scatter. The younger smaller ones lag behind on their shorter legs and she picks one out. The juvenile Thescelosaurus recognizes this, dodging to the side as the mother Quetzalcoatlus‘s massive beak snaps right past. She arcs through the air for a second strike, this time landing the precise blow she is looking for. The little dinosaur is slammed to the ground and dragged forward before being dropped and trampled by the pterosaur’s landing gallop. In the end, the hunting mother stands over her kill, resting for the moment from the intense physical activity of aerial hunting. Her attention once again on her surroundings, she notices that a bright light has illuminated the trees at the edge of the clearing. Turning her head, she sees a blinding light in the other direction where the horizon’s star had been which casts shadows through the monkey puzzle trees before disappearing beyond the horizon. She enjoys the last quiet moment of her life.

3,000 kilometers to the south, a 10-kilometer-in-diameter asteroid has torn through the Earth’s atmosphere in seconds and released 300 zettajoules (that is, 300,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 Joules, the equivalent of 72 trillion tons of TNT, or the equal of 4,800,000,000 Hiroshima bombs) of energy on impact and vaporization. Immediately the air gets warmer and the sky gets brighter as sunlight and glowing heat glimmer off the billions of tons of material shot into space. The mother Quetzalcoatlus is beginning to feel uncomfortable when the shockwave hits, the ground buckling with a category-11 earthquake that flattens trees all around her, crushing some of those dinosaurs that still happen to be nearby. She is thrown from her feet but quickly gets her bearings, recognizing that the kill is not worth remaining in whatever sort of dangerous situation she has just found herself in. She leaps into the sky, narrowly avoiding tumbling trees, and finds the warm air full of updrafts that carry her higher and higher. But safety up here is an illusion. The air front hits next as winds travel at a thousand kilometers an hour, suddenly throwing her forward. She accelerates with G-forces that throw her into immediate unconsciousness, sending her limp body flung northward through the air. The heat of the winds starts to cook her.

Many kilometers north when she crashes back into the ground, she is dragged through debris of fallen trees, tearing away her limbs and head. In the several places her body lays, the sky above begins to blacken as bright lights streak down from above. A rain of fire and brimstone, molten rock more specifically, heralds the coming of the apocalypse under wrathful heavens. The age of reptiles approaches its end because of the chance whims of orbital mechanics.

Our Place in a Busy Universe

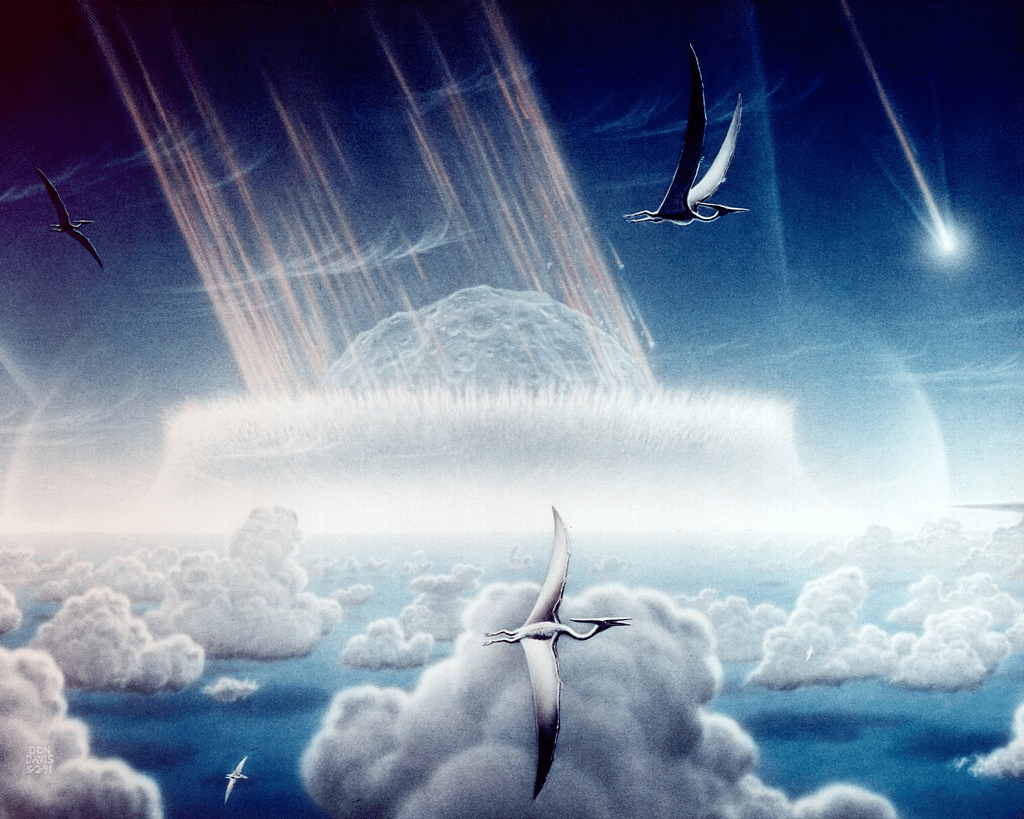

1998 illustration by Donald E. Davis of the Chicxulub impactor touching down 66 million years ago. That Pteranodon is screwed.

It is probably not difficult to recognize the event my dramatization above refers to. 66 million years ago, a colossal asteroid (or another impactor such as a comet) struck what is now the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico and delivered a killing blow that according to most scientists was the prime mover on the end of the age of the non-avian dinosaurs. Since the impact cause of the extinction was proposed in Alvarez (1983) and the crater identified in Hildebrand (1991), it has become ingrained in the popular consciousness, quite deservedly, as an example of the ultimate apocalyptic event. Disaster movies have adopted extraterrestrial impactors as a stock event and news organizations make sure to capitalize on the anxiety of death from space. And… I get it. This article, even if I am interested in looking at the science and history around these events, is motivated by that same sense of wonder at destructive power. Much has been written about the Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction and we will get into it, but I think such a fascinating topic deserves some wider exploration and context. Today we will look at the natural and human history of asteroids, comets, meteors, and meteorites with specific focus on what happens when celestial bodies collide dramatically. In order to tell this story, we need to go back much further in time to understand where these materials came from.

This image of the star HL Tauri was taken by the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, an array of radio telescopes in Chile. HL Tauri is 450 lightyears away and believed to be less than 100,000 years old. It displays a prominent protoplanetary disk, much like the Sun would have had in its nascent ages. It is within the Taurus Molecular Cloud, a large region of interstellar debris that acts as a nursery for new stars.

Our Sun, and thus the Solar System, came into being about 4.56 billion years ago. Seeing back this far is difficult, so we have only a few means of learning about this. Firstly, we can look at the analogous formation processes of other stars. As imaging technology of distant star systems has improved, different stages of stellar evolution have become more visible and, in some cases, we have gotten some picture of what orbits the stars, be it planets or large disks of debris. Protoplanetary disks, dispersed orbiting rings of materials that have yet to settle in a young star system, have been observed which test earlier models about system development. Secondly, we have the overall structure and composition of the modern Solar System. Formation models need to account for the elemental and isotopic makeup of the system as a whole as well as how these materials are distributed (for example, are some of them more common in bodies further or closer to the Sun?). The relative sizes of the planets, what distances they have from one another, and the fact that the rocky planets are all closer to the Sun than all the gas giants are of interest. But planets also tend to have active geological processes and weather that efface traces of their origins over the course of billions of years. As such, significant objects of the early Solar System are somewhat hard to find on them. This is where meteorites come in handy.

The technical definition of meteorites is rocks deposited on a planet or moon from outer space. Pretty simple. Meteorites constitute the samples of asteroids we have on Earth and can study by direct physical means as opposed to studying them in space. It is important to note that the physical object is changed in the process of being deposited. Meteorites on Earth essentially never comprise whole asteroids because during entry to the Earth’s atmosphere, the friction of falling at supersonic speeds (some can reach speeds of 71 kilometers per second) heats their exteriors and vaporizes much of them. Most meteors (such objects while they are in the atmosphere) do not make it to the ground at all. For a meteorite to be deposited, the source object must be large enough to not be vaporized entirely while also small enough to not cause an absolutely catastrophic impact. It is also possible that one impact event breaks up into multiple meteorites. Just like rocks formed on our planet have classifications based on their compositions, structures, and formation histories, likewise a typology exists for varieties of meteorites. Each of these has a number of classifications within it but the three major categories are chondrites, primitive achondrites, and achondrites (alongside other miscellaneous objects).

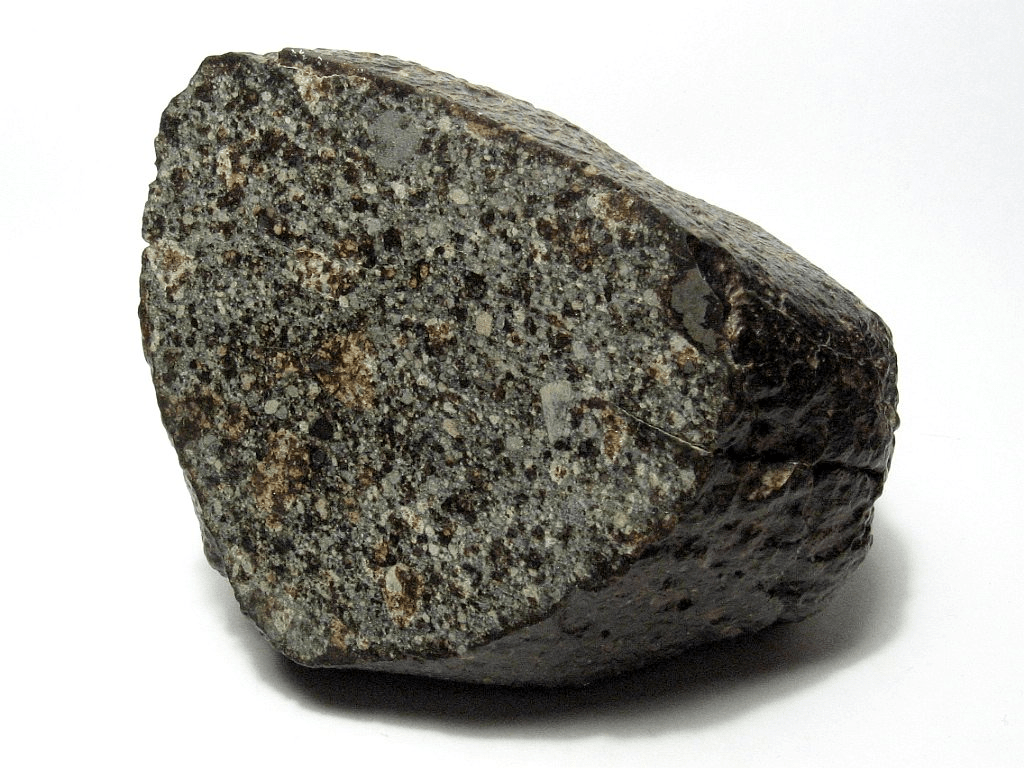

An example of a chondrite meteorite, NWA 869 (labeled Northwest Africa because it comes from unknown provenance through a market in Morocco) shared by Wikimedia contributor H. Raab. The near side has been cut and polished flat, showing the internal structure where chondrules are visible.

Chondrite meteorites are those which scientists consider “undifferentiated,” that is, their internal contents are not moved around to form patterns by processes such as gravity and melting. They contain a jumbled mix of materials in a peppery matrix. Round bits of material called chondrules are easily visibly recognizable. Chondrites are further separated into carbonaceous and noncarbonaceous types, depending on the relative composition of carbon (greater or less than 3%) which typically takes the form of part of compounds like graphite. The jumbly nature of them generally shows that the major process of their formation is accretion, which is when gravity and time cause small pieces of material to stick together to gradually form bigger and bigger objects.

This meteorite is NWA 3151, an example of primitive achondrite called brachinite, photographed by Flickr user Jon Taylor.

Primitive achondrites, fairly straightforwardly, are those meteorites which formed by accretion and still show the chondrules of the chondrites but which have had some partial melting processes in their development but which was not extreme enough that it can be said that the rock itself crystallized from melted material. Older scholarship has often classified them within the achondrites but more recently specialists have seen use in labeling them separately.

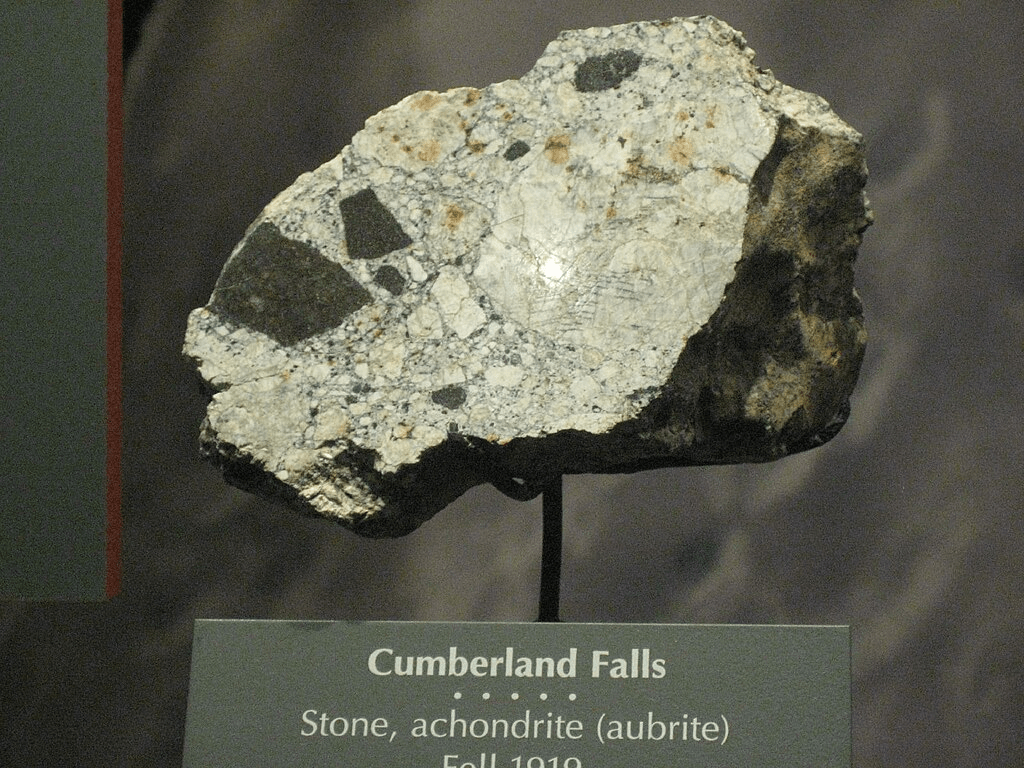

The Cumberland Falls meteorite, which fell in Kentucky, USA in 1919, is an example of an achondrite meteorite called aubrite. This image is from Flickr user Claire H.

Achondrites, called in some papers I read as “differentiated meteorites,” are meteorites which crystallized from molten material. They are thus technically also igneous rocks. This sometimes includes iron meteorites (meteorites composed of an iron-nickel alloy called meteoric iron) and sometimes not. Achondrites are often formed by impact events themselves. When a massive impact occurs, it can fling colossal amounts of ejecta into space, which then cools down and solidifies. Certain celestial bodies within a certain distance of Earth have produced quite a few such achondrite meteorites that provide pre-delivered samples of their surfaces at times in the distant past. The main sources of these are the Moon, Mars, and Vesta, the latter being the second largest object in the Asteroid Belt after the dwarf planet Ceres. It is not entirely unlikely that some of the ejecta from the impact on our world at the end of the Cretaceous was sent out to these bodies as well.

The types of asteroids we have are in many cases witnesses of the various stages at the origin of our Solar System. It is through the solidification of the oldest meteorite material that scientists have been able to radiometrically date these processes. Stars form when gravity brings together so much material that the pressure under the mass of that material begins the process of nuclear fusion, combining the nuclei of lighter elements to create heavier ones, releasing immense amounts of energy. In looking into the cosmos, scientists find that many of the newly emerging stars are in regions of space filled with vast molecular clouds or nebulae where free hydrogen can coalesce. It is believed that the Sun formed in a region like this, but since objects in space are non-fixed and moving, after billions of years, the Sun is not necessarily in the neighborhood of any other stars from this same nursery. (Our Solar System takes about 230 million years to circle the galaxy, meaning it has done so just over 20 times. The rate and directions of our ancient sister stars’ movements are not necessarily the same and so after this extreme amount of time, it is likely they are in vastly different regions of space. Also, for a reference point, one galactic orbit of 230 million years ago was the Mid-Triassic Period, around the time the first dinosaurs were appearing. Two was the Ordovician period when our ancestors were jawless fish. Three galactic orbits ago, animals had not evolved yet. Each of these intervals accounts for 5% of the history of our planet.) The Sun is considered a second-generation star, meaning that its chemical makeup is indicative of it having formed following the death of an older star, which scientists supporting the hypothesis have named Coatlicue (this is a reference to Aztec mythology where Coatlicue was the mother to the solar deity Huitzilopochtli). The parent cluster Coatlicue was part of would have had somewhere around 1200 stars. Isotopic materials indicate the presence of at least one (and possibly several) nearby supernovae. A supernova is the explosive death of a giant star and one of the most extreme physical conditions in the universe. Normally the nuclear fusion at the cores of stars is limited in how high up the periodic table it can climb in constructing new elements. Following element 26, iron, conditions simply are not extreme enough to build larger nuclei. But supernovae are on another level and during the process of blowing off their outer layers in violent, destructive, and creative displays, they can briefly produce elements much higher on the periodic table. As such, heavier elements (especially in radioactive isotopes that only last so long after formation and therefore can be used to date the events) can be signs of supernovae in the past. Even after the Sun began to shine, it was surrounded by material that would have taken the shape of a protoplanetary disk. Over time, much of this material would fall into the Sun, escape, or form other structures in orbit around the star. Today the Sun accounts for 99.86% of the mass in the entire Solar System. Every planet, moon, asteroid, comet, and dwarf planet is in what remains.

Most meteorites today are older than 4.5 billion years and come from the Asteroid Belt, a region of space scattered with orbiting smaller objects between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Within chondrite meteorites, the relatively separated internal components allow for the identification of radiometrically dated materials. CAIs (calcium-aluminum inclusions) provide trapping for material that can be used for uranium-lead dating. Dates on these have pointed to times as far back as 4.568 or 4.567 billion years ago, slightly before the Sun is believed to have first lit up, if current models are decently accurate. These chondrules would have accreted into the asteroids themselves within about 2-4 million years after the Solar System formed. Achondrites seem to have largely formed in an overlapping period of time, but which started earlier. Iron meteorites seem to have differentiated within the first 2 million years of the Solar System. By “differentiation,” scientists mean that natural processes effectively sorted the iron and nickel that composes them into one mass, generally through relative settling by density. This is the same process that is the reason that Earth has an iron-nickel core for instance; when materials are hot enough that they become molten, denser materials will settle towards the center of gravity compared to lighter materials. Iron meteorites thus represent the cores of larger bodies that have been shattered apart in ancient collisions. Another source of heat for achondrites would have been radioactive decay. The early Solar System seems to have been full of heavy elements created by supernovae, which would have included unstable isotopes. Radioactive decay generates heat and this could power differentiation. The particular radioisotope of interest is 26Al or aluminum-26. Aluminum is element 13 on the periodic table and therefore completely in the range of elements that can be made in the normal fusion processes of a star’s lifetime, but 26Al also has a half-life of only 717,000 years, meaning that its significant presence in something indicates relatively recent formation, in this case being shot out by a supernova. In meteorites today, it is almost entirely decayed into its daughter product 26Mg, magnesium-26, but the proportion of the two can be used for radiometric dating. At a certain point, chondrites which were forming by accretion did not have any more of this source 26Al (the supernova that supplied it was no longer in the immediate past) and this decay heat source disappears from younger meteorites. Over the next tens of millions of years, some objects in the early Solar System began to attain very large sizes, first by accretion themselves and then gravity and heat differentiated their makeup into layers. These became planetesimals and then planets.

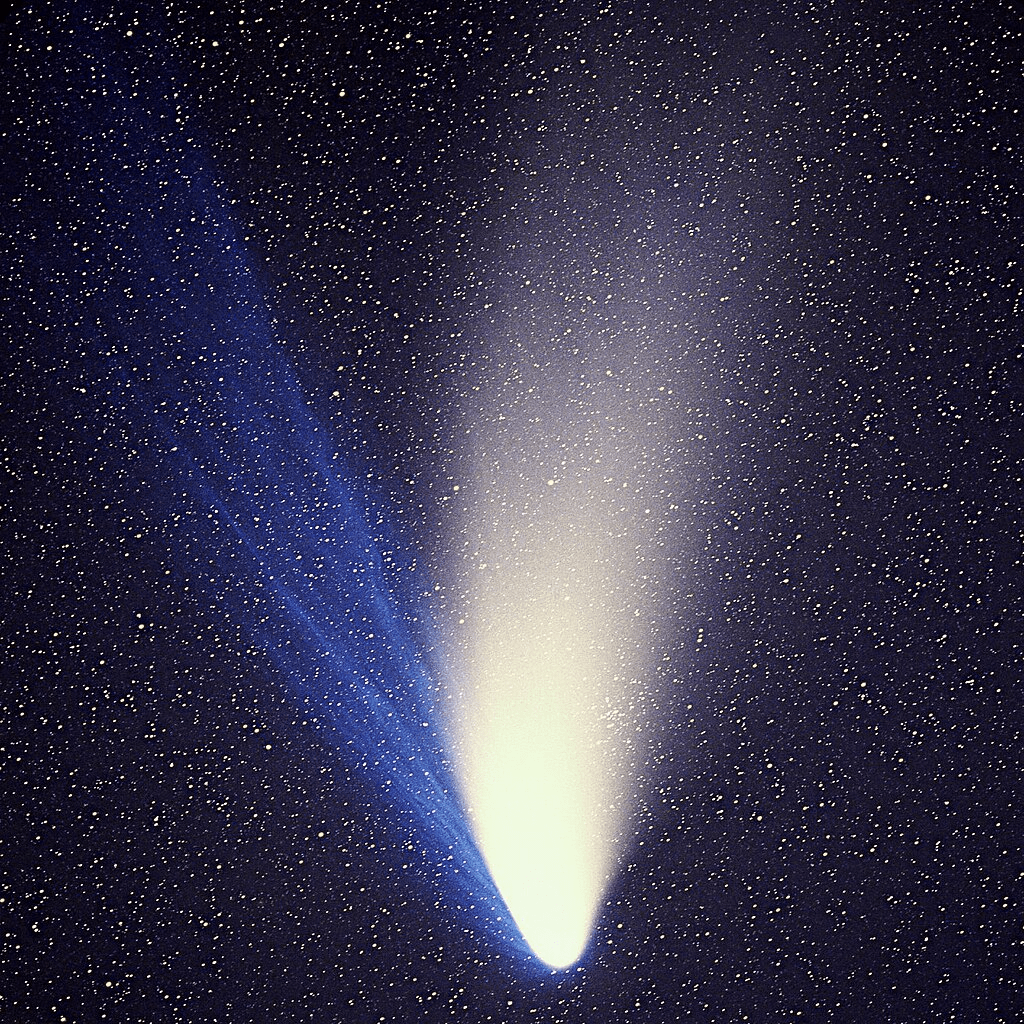

The 1995 appearance of Comet Hale-Bopp as it passed through the Inner Solar System in 1995, presented here in a photo from the Johannes Kepler Observatory in Austria. This was the brightest comet seen from Earth during the 1900s and is the same one that the Heaven’s Gate cult famously committed mass-suicide in order to board and escape this material plane.

While I am mostly focusing on asteroids, comets have their place in the story of extraterrestrial impactors and I should treat their origins shortly here. Unlike asteroids which are made of solid rock and/or metal, comets are made of other materials that cause them to release gases when exposed to the Sun, which forms the tails sometimes visible from Earth. Generally, the body (or nucleus) of the comet itself is made from ice and dust and the tails represent sublimation (direct change of material states from solid to gas, as often happens in the vacuum of space when very cold things warm) of frozen material. Less is known about the formation history of comets than asteroids because of the lack of residue they bring to Earth, both due to the materials they’re made from and the fact that they spend most of their time much further away in the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud far beyond even the outermost planets. Those comets which we are able to observe are those with extremely eccentric elliptical orbits which occasionally swing through the Inner Solar System close to the Sun. The only comet samples ever brought to Earth were by NASA’s Stardust craft, which did a sampling of the dust off of comet Tempel 1’s tail from a distance of 250 kilometers in 2004 before sending back a capsule of the samples which landed back on Earth in Utah, USA in 2006. The sampling alerted scientists to the fascinating presence of organic compounds on the comet and later analysis led to an announcement in 2014 that the same probe had collected seven microscopic interstellar dust particles likely dating to the origin of the Solar System.

Comets in general can be divided into two different “families”: Jupiter-family comets or JFCs and long-period comets or LPCs. JFCs (no, it’s not a bit) have orbital periods of less than 200 years while LPCs have those which are much longer. JFCs are associated with Jupiter because they tend to pass through Jupiter’s orbital range. It is generally thought that the differences between the two have to do with where they are formed. JFCs were formed closer to the Sun and have erratic orbits presumably due to their long histories of being affected by the orbital migrations (that is shifts over time, especially in distance from the Sun) of the planets, whose orbits they cross over. Comet compositions also appear to evolve over the course of their histories. Unlike the far more solid asteroids, comets regularly go through state changes that restructure them, especially when closer to the Sun.

In the protoplanetary disk 4.6 billion years ago, some accreting objects began to quickly amass truly significant size. First, they became planetesimals and then protoplanets and finally something like the planets we know today. All of the planets we know in the system today seem to have formed within tens of millions of years of the birth of the Sun and then stopped growing as they finished mopping up the material in their particular orbital neighborhoods (actually having largely cleared their orbital path is one of the three characteristics of a planet in the Solar System following the definition of the International Astronomical Union, along with orbiting the Sun and having a rounded shape due to sufficient mass). Based on a few lines of evidence including hafnium-tungsten radioisotope signatures from Earth and meteorites, the period our planet is considered to have formed over is between about 38 and 120 million years after the origins of the Solar System. An interesting comparison case is Mars, which seems to have formed over a shorter time, between 2 and 10 million years after the origin of the Solar System. The reason Mars stopped growing early appears to be Jupiter, its gargantuan looming neighbor, which hogged up material over a very large area of space, eventually starving Mars. It also appears to be Jupiter’s disruptive gravitational influence over the Asteroid Belt (between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter) that prevents too much accretion from happening there on its own, leaving the region full of smaller objects. Discussions of the formation of Solar System objects also make use of a concept called the “snow line,” a distance away from the Sun after which volatile materials (things like water and gases) were cold enough and affected by the solar wind little enough to accrete into bodies on their own. On the inside of the snow line are rocky planets and rocky asteroids while on the outside there are gas giants and icy comets. In the early Solar System, it is probably likely that many more protoplanets existed that have since been either ejected from the Solar System or been destroyed in collisions.

An explanatory image from NASA showing two planets crashing into each other.

In Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, it is in this early maelstrom that the largest encounter with an extraterrestrial impactor occurred: what for all intents and purposes was a planet the size of Mars. The elegantly named “giant impact hypothesis” is the most commonly accepted scientific idea about the origin of the Moon. According to the model, around 4.5 billion years ago in the early Hadean Eon of Earth’s history, a protoplanet, often nicknamed Theia, which had either formed in or wandered into the Earth’s orbital path smashed into the young Earth at an oblique trajectory, liquidating the still-solidifying crust and throwing off massive amounts of material into space in a high-speed orbit. The young Earth ended up with a ring system that gradually underwent accretion of its own and became the Moon. The primary evidence for this hypothesis as opposed to others is the comparison between the compositions of the Earth and the Moon. If the Moon had, as older hypotheses often suggested, formed in a similar manner to the planets from the protoplanetary disk and simply been captured by the Earth’s gravity, its similar zone of formation around the Sun would likely lead to a similar composition. But unlike the Earth, the Moon is relatively lacking in many heavier materials like iron, while also having many similarities with the Earth’s crust and mantle. If the Moon formed later from the Earth’s own material, which had been ejected into space by such a catastrophic impact event, it would make sense that it would have compositional similarities to the outer layers of our planet while still lacking those materials that largely settle in the middle due to density, like the iron that makes up our planet’s core. This impact stands out from others in our planet’s history on account of its scale and the fact that it happened so early that the details of it are hard to study precisely due to the ravages of geological and cosmic time, but it is also probably the most impactful impact in the history of our planet.

The Hadean Eon that makes up the first 500 million years of our planet’s story is so-called after the Greek underworld god Hades because it was a truly hellish place. The intense heat of impact events and the volcanism caused by the planet’s materials settling into layers meant that the surface was frequently molten in portions of the planet. Billions of years of geological activity may have erased most early impact evidence on Earth but evidence of a tumultuous period in the Inner Solar System exists in the more static surfaces of the Moon and Mercury as well as that of Mars, which used to be geologically active but has become less so due to a solidifying interior, meaning most large natural structures there are billions of years old. On these worlds, impact events indicate a period of more regular catastrophic impacts starting after 4.2 billion years ago (meaning the planet was several hundred million years old and had largely already solidified on the surface and differentiated in the interior) and continuing potentially as late as 3.5 billion years ago in the Archean Eon. Scientists title this phase the Late Heavy Bombardment or LHB. The major basins that visually define the face of the Moon were formed in this period, almost all before 3.7 billion years ago. Several explanations exist for why this occurred but astronomers have increasingly come to believe that the four gas giants in particular have migrated out further from the Sun than where they formed. The Asteroid Belt is strongly gravitationally affected by the orbital resonances of the giant planets and perhaps orbital shifts contemporaneous with Earth’s late Hadean disturbed the orbits of objects in the Asteroid Belt and sent many of them passing through the Inner Solar System. Many depictions of this period show rocks raining down from the sky in continuous volleys but it’s important to remember that in reality this phase lasted 700 million years, longer than the entire history of animal life, and if tens of thousands of impactors hit, that is still less giant impacts than once every thousand years.

Somehow, amidst all of this, life emerged. We are limited in what we can say about the Hadean because rocks are largely absent but small pieces of geological material are not. Of particular focus are zircon crystals, which are relatively resistant to both chemical and physical weathering and also capture other materials within them, lending themselves to both radioisotopic dating and use for studying the chemical makeup of their environment. Using silicon and oxygen isotopes in these crystals, scientists in recent years have proposed that they show evidence for the existence of life as well as a substrate it could live in as early as 4.1 billion years ago, which would mean that life not only dates to the Hadean but also was on Earth within 400 million years of the planet forming and was present for at least most of the LHB. The first organisms on Planet Earth would have weathered and endured through impact events of scale and frequency that later life would buckle from. A certain number of readers are no doubt already raising their hands to talk excitedly about panspermia. So let’s address that for a moment.

Abiogenesis is the process by which living things develop from nonliving materials. The term is used both to discuss whatever process must have happened on Earth in deep prehistory to kickstart the evolution of living things and as a theoretical term in astrobiology (the scientific investigation of the potential for life beyond Earth) for the patterns that may lead to life on other worlds. While in recent decades progress has certainly been made on understanding abiogenesis, a complete knowledge of the process currently evades science. Panspermia is a hypothesis that suggests that looking for answers to the problem solely on Earth will not yield solutions because living organisms on Earth actually just represent a colonizing branch of an older evolutionary tree. Panspermia advocates suggest that we are aliens and that life first crashed onto Earth from outer space on impactors. I am not convinced on panspermia but the hypothesis does have a lot of scientific plausibility so I will give it its strongest form here, based on the reading I have done by the small minority of scientists who support it. Life is ultimately an extremely complex chemical process and many of the chemical components of life have already been observed in our universal neighborhood, such as when NASA’s Stardust identified organic compounds within comet Tempel 1. Life could have originated either on small traveling bodies such as these or on planets or moons. Impact events demonstrably throw off ejecta that can move material between planets. Could an extreme microbe survive, active or dormant, on impact ejecta thrown off into space for long periods of time and then survive again on reentry to a new world’s atmosphere? Maybe. If so, regions of space may in fact have life on multiple worlds which grows off the same evolutionary tree. Mars and Earth for example are two of each other’s most significant trading partners of ejected material. While Earth was in its early phases, Mars was actively more hospitable for a while with flowing liquid water and a thicker atmosphere. Could life have at one point existed on Mars and hitched a ride on a LHB impact detritus and come to Earth, where it flourished while Mars slowly died? It is controversial among panspermia advocates if the limits of this spreading are within a star system or if the process could even seed life on interstellar scales. For the minority of the minority that go for the latter, they argue that galactic orbits frequently, in geological timescales of course, bring stars into close proximity with nebulae, where collisions between the distributed matter of such nebulae and the objects such as asteroids and comets that travel with star systems could exchange microbes. Some of these scientists imagine a universe not long after the Big Bang where densely packed cosmic environments distributed extremely early organisms around the universe to develop later. If this sounds like it’s all getting carried away, most scientists in relevant fields agree, not because panspermia is disproven (no comprehensive model for abiogenesis on Earth is yet accepted either) but because, they tend to argue, it just kicks the mysteries of abiogenesis out to space, still leaving the problem for how it happened in the first place, while creating more explanatory issues. It also seems to suggest that the universe is more teeming with life than our searches yet make it appear. Nevertheless, the question of the relationship between the origins of life and extraterrestrial impactors is fascinating to ponder and certainly worth doing, if we can remember to prioritize objectivity in deciding what we believe and how strongly.

That said, the role of extraterrestrial impactors on the history of life has certainly not been small.

The Restless Heavens in the Story of Life

I am going to be making frequent references to the periods of the geological timescale in this portion of the article. For the ease of readers who are not used to engaging with deep geological chronology, here is a table of the standard divisions of Earth’s history and their names. In order from largest to smallest, there are standardized eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages. I will be ignoring the epochs and ages for now.

| Eons | Eras | Periods | Start date in millions of years ago |

| Hadean | 4567.3 | ||

| Archean | Eoarchean | 4031 | |

| Paleoarchean | 3600 | ||

| Mesoarchean | 3200 | ||

| Neoarchean | 2800 | ||

| Proterozoic | Paleoproterozoic | Siderian | 2500 |

| Rhyacian | 2300 | ||

| Orosirian | 2050 | ||

| Statherian | 1800 | ||

| Mesoproterozoic | Calymmian | 1600 | |

| Ectasian | 1400 | ||

| Stenian | 1200 | ||

| Neoproterozoic | Tonian | 1000 | |

| Cryogenian | 720 | ||

| Ediacaran | 635 | ||

| Phanerozoic | Paleozoic | Cambrian | 538.8 |

| Ordovician | 485.4 | ||

| Silurian | 443.8 | ||

| Devonian | 419.2 | ||

| Carboniferous | 358.9 | ||

| Permian | 298.9 | ||

| Mesozoic | Triassic | 251.902 | |

| Jurassic | 201.4 | ||

| Cretaceous | 145 | ||

| Cenozoic | Paleogene | 66 | |

| Neogene | 23.03 | ||

| Quaternary | 2.58 |

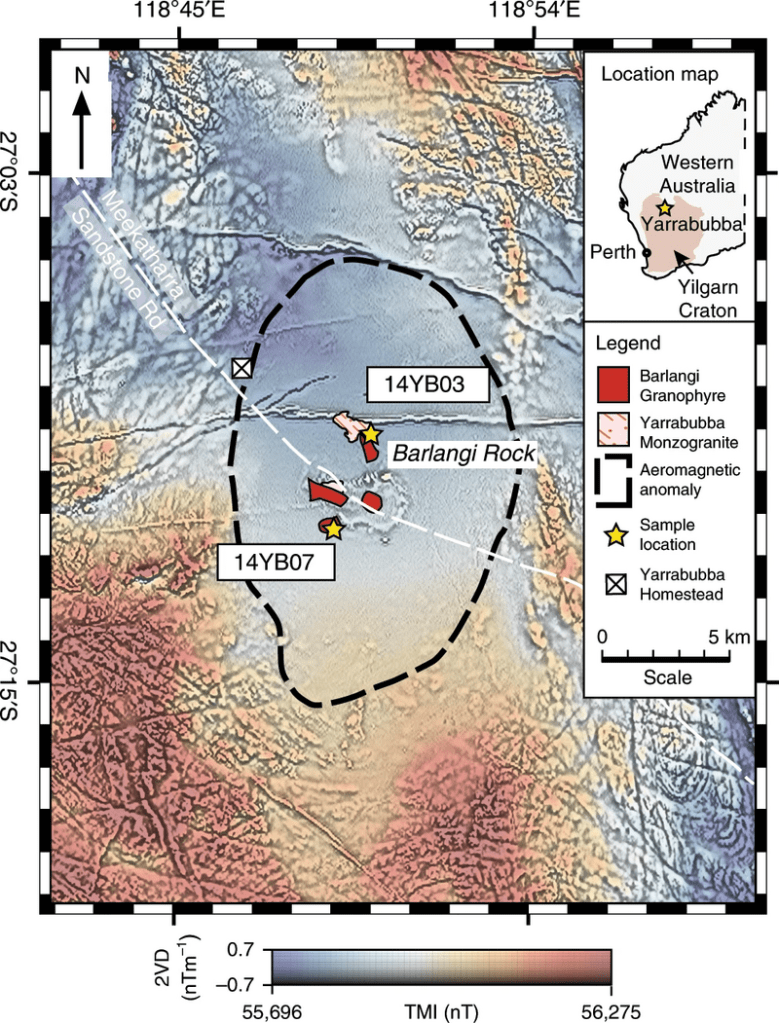

A map of the Yarrabubba Crater in Western Australia, the oldest relatively agreed-upon impact structure on Earth, by Erickson et al. The crater is on the north side of a geological region called Yilgarn Craton, which is one of the regions with the oldest extant rocks in the world, preserving rare records from the Hadean, Archean, and mainly Proterozoic eons.

Around 2.229 billion years ago, the Earth was in the midst of the Huronian glaciation, an incredibly long ice age that lasted from 2.5 to 2.2 billion years ago during the Siderian and Rhyacian periods. It was here in the Rhyacian that the first eukaryotic life emerged, cells with nuclei and complex organelles that would become the future ancestors to the likes of animals, plants, and fungi. What is now Western Australia was covered by a vast south-polar continental ice sheet. And then, suddenly, an object some 7 kilometers in diameter cut down through the atmosphere and smashed into the ice, forming an instant crater some 70 kilometers in diameter and vaporizing somewhere between 8.7×1013 and 5.0×1015 kilograms of water directly into the atmosphere, no doubt impacting the climate of the planet in following years and prompting, billions of years later, scientific discussions about the relationship between impact-induced climate events and the subsiding of the Huronian glaciation. Today, the Yarrabubba Crater, named for an Australian Outback sheep and cattle station in the area, is the oldest uncontroversially identified impact crater on Planet Earth. Others have been proposed but most have been rejected or remained controversial. The Yilgarn Craton region of Western Australia makes this possible: a vast region of rocks from across Precambrian (the common gloss for all eons before our current Phanerozoic) time not overwritten or destroyed by more recent processes. The zircon crystals I mentioned earlier are also largely from this region. How many deep prehistoric impacts took place in the Proterozoic Eon where the record has not been so kind as to bring us the story? It is hard to say.

NASA image of Vredefort Crater in South Africa with the Vaal River running through it.

Only some 200 million years later, the largest known impact crater on Earth was formed. 2.02 billion years ago, the Earth was in the Orosirian Period and the continents were in the process of merging together into the great supercontinent of Columbia, leading to mountain ranges being pushed up globally. Kalaharia, a part of what would later merge to become Africa, was part of the northeast extremity of Columbia at similar latitudes to where Canada and Russia are today. Unlike in the Rhyacian Period, the coming cataclysm was not about to occur on an ice sheet but in the middle of continental land. And it was about to be much bigger. Vredefort Crater is located today in the Free State province of South Africa and, while only part of it remains intact today, is estimated to have originally been around 172 kilometers across at the time of formation. There is some debate as to the size of the impactor itself but recent models making use of computer simulations have shown that it is plausible that existing conditions could have been formed by either an impactor which was 25 kilometers wide and traveling at 15 kilometers per second or which was 20 kilometers wide and traveling at around 25 kilometers per second. This means that even on the low end of size estimates, the impactor was twice as wide as the more famous dinosaur-killer and since volume scales in two dimensions when length scales in one, something like four times the total volume at the lowest. With the amount of material that would have been vaporized or thrown skywards, questions exist as to the extent that gas released from the impact may have contributed to a temporary greenhouse effect or conversely how soot in the atmosphere almost certainly caused a dark global winter for some period of time. It is the sort of event that demands comparison with the more famous end-Cretaceous impact but which also in some ways feels incomparable because of the lack of macroscopic life to undergo a mass extinction. Microorganisms, always the survivalists, took the hit and carried on.

A third very large Precambrian impact crater can be found in southeastern Ontario, Canada, near the Great Lakes. The Sudbury Basin has been identified as a 1.849-billion-year-old impact site for various reasons but the site also presents an interesting case in how impact craters are to be studied. Since the impact happened, the particular region of Ontario has been subjected to mountain formation and so many impact features are distorted or overwritten by orogenic processes.

538.8 million years ago, the Paleozoic Era began with what has been termed the Cambrian Explosion. A rapid diversification in animal life led to teeming seas full of arthropods, mollusks, and the first vertebrates. While things on Earth were speeding up, events in the Solar System were slowing down. The geological record generally supports the notion that impact events have become rarer and rarer as our celestial neighborhood has aged, probably largely because the objects that lasted a certain amount of time had stable orbits that tended not to hit anything else and there was just less loose material altogether. As such, despite everything that I will soon discuss, the last half-billion years have been relatively pleasant in terms of impact events. This has most certainly been a boon to the animals and plants that have overtaken the planet in that time. Around 375 million years ago in the Devonian Period, animals like Tiktaalik became the first vertebrates to move towards walking instead of swimming and as they came onto land, they joined a new ecosystem of land-dwelling plants, fungi, and arthropods. 299 million years ago, the Permian Period opened on a planet fresh for the taken for early stem-mammals like Dimetrodon. The world’s continents were increasingly joined together into one new supercontinent called Pangaea. The southern part of this, Gondwana, was already very much conglomerated and included Australia, always seemingly a favorite of impactors.

In the Early Permian, what is now South Australia seemingly came under impact from space. The East Warburton Basin, located in the northeast portion of the state, contains not one but two seeming impact structures, dated from around 298 to 295 million years ago and primarily identified through shocked quartz. The region has an excellent Paleozoic geological column with mountains raised in the Permian ringing magmatic basins which rest where the rock column from the Ordovician to the Devonian is missing. If this interpretation is correct, two impact structures in the same area that formed effectively simultaneously is almost certainly not separate impactors but rather one object breaking apart before it hit the surface. In orbital mechanics, the Roche limit is the radius from a central object at which another orbiting object will have its own self-gravitation overpowered by the object it orbits and get ripped apart. A significantly large impactor that enters an unstable orbital path around the Earth will eventually hit the Roche limit and start to break. Perhaps this is what happened to the impactor that struck the East Warburton Basin in two different places. Aside from icons like Dimetrodon, the Permian Period is probably most famous for mass extinction. Two separate mass-extinction events struck in this period which are now becoming widely recognized by scientists as separate events: the Capitanian Extinction around 259 million years ago and the End-Permian Extinction (the famous Great Dying) around 252 million years ago. These respectively are considered the third and first deadliest extinction events in the last half-billion years. However, both are associated not with asteroid impacts but instead extreme long-running volcanism (the eruption processes that created the Emeishan Traps in modern China and the Siberian Traps in modern Russia respectively). The impact event that may have led to the structures in the East Warburton Basin is not associated with, at least as has been identified, a major extinction event. Perhaps in the future, discussions will take it into account regarding how ecological developments relate to impact events. Alternatively, there is debate as to whether these structures are impact-created at all and maybe time will remove them from this discussion altogether.

A montage of dinosaurs from Wikimedia Commons. This image serves the reader as a reminder that dinosaurs were and are, to use a technical term, really fucking cool.

As the Permian ended in volcanic hell, a mere 17% of genera on Earth scraped through into the new world that followed. Among these, were the ancestors of the dinosaurs, which some 20 million years later began to take their recognizable form. The Mesozoic Era would be an age ruled by dinosaurs and after the diverse ecological arena of the Triassic Period came to a close, dinosaurs would become so successful that they would dominate nearly every terrestrial megafauna niche for the entire Jurassic and Cretaceous on all continents. And… well… you know what comes next.

Dinosaur Apocalypse

At the end of the Cretaceous Period some 66 million years ago, the planet was warmer than today and with higher sea levels. Over the course of the Mesozoic, Pangaea had broken first into the northern and southern supercontinents of Laurasia and Gondwana and then these had each broken apart east-west to open the young and thin Atlantic Ocean. In the Early Cretaceous, the debut of flowering plants had spurred developments in animal evolution, including the coming of pollinating insects and various new groups of herbivorous dinosaurs such as the duck-billed hadrosaurs that specialized in the new foliage. The Late Cretaceous was a time of grand horned ceratopsians and fearsome tyrannosaurs, armored ankylosaurs and fast-running ornithomimosaurs. Pterosaurs were reaching colossal sizes and birds were joining them in the air. In the oceans, spiral-shelled ammonites and a vast array of fish were fed on by marine reptiles such as long-necked plesiosaurs and fully aquatic lizards known as mosasaurs. Beneath the underbrush in the dinosaurs’ kingdom, mammals scurried about, not getting much larger than a dog but having a great variety in forms and reproductive strategies. Compared to all the impacts that have been discussed thus far, the incoming one occurred in a world that would have appeared much more familiar to us and full of more charismatic creatures. It is easier to understand and also to be horrified at.

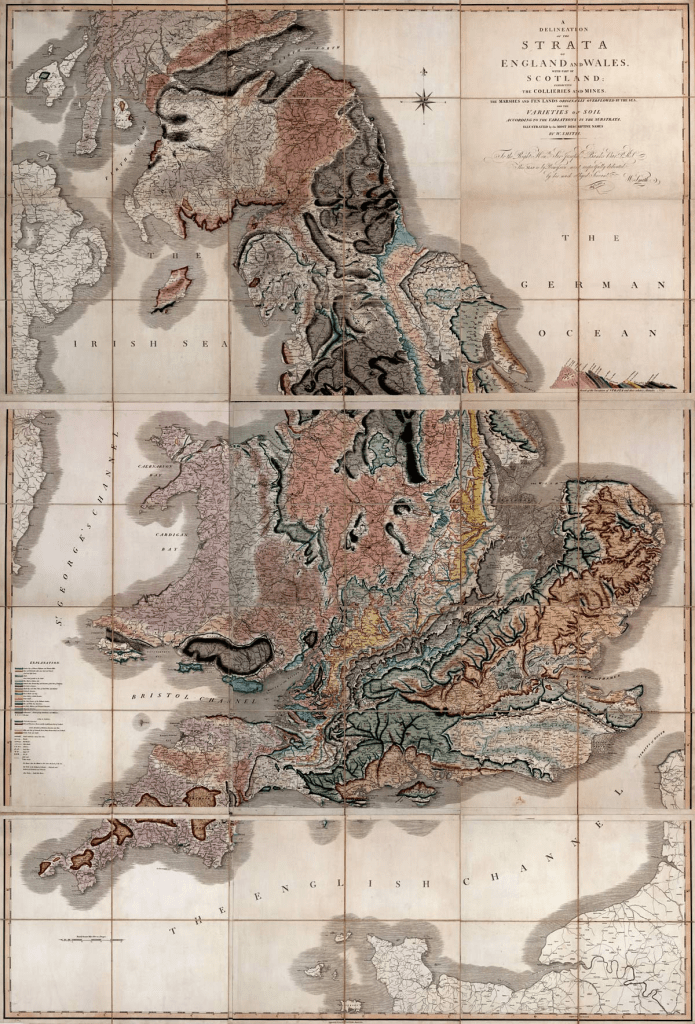

This is William Smith’s 1815 map titled A Delineation of Strata of England and Wales and Part of Scotland, the first comprehensive mapping of a country’s various geological strata by time period. The map was informed partly by fossil remains according to Smith’s “law of faunal succession,” meaning that its division between Cretaceous and “Tertiary” (an outdated geological period that includes what is now considered the Paleogene and Neogene) rocks represents the first known documentation of the end-Cretaceous extinction boundary.

The story of the research history of the Cretaceous extinction event is almost as interesting as the event itself. Recognition of the event in some form goes back to the earliest days of scientific geology. In the early 1800s, the “father of English geology” William Smith recognized as others already had that rock layers deposited vertically with newer material settling on older material, but that frustratingly processes since deposition could contort and mix up the layering. Smith’s breakthrough was that rocks of similar ages contained like fossils and therefore if a geological sequence was confusing, its layers could be dated by being matched with index fossils from sequences already understood. This was the “law of faunal succession” and it gave Smith a tool he put to great use in beginning to map and periodize the ages of rock throughout Britain, culminating in a completed map in 1815. The geological timescale was born. Extinction and evolution–the latter was actually called “transformism,” a clunky term that Charles Darwin would vastly improve and replace later in the century–were new concepts at this point (being pushed forward by two Frenchmen, Georges Cuvier and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck respectively, who were contemporaries of Smith) and so what might appear to us a description of extinctions and evolution was something somewhat novel and connections we’d consider obvious were sometimes not made. Among the data Smith gathered was the curious break between the Cretaceous and what was called in Smith’s day the “Tertiary,” a period later broken into the Paleogene and Neogene (the division Smith found is known as the K-Pg boundary today because of the abbreviations for “Cretaceous” and “Paleogene”). Whereas much of the fossil record showed a smooth transition between species, this division seemed to have very few species cross it with wildly different fossils postdating it from predating it. Some scientists who followed such as Charles Lyell thought that this strange division must simply represent a preservation gap and that a vast missing amount of time must exist in that space. Mass extinction was an odd concept to grasp for some.

Sir Richard Owen creates the word “dinosaur” in 1841 in this text from Report on British Fossil Reptiles, Part II.

Smith was informed primarily by the distribution of marine life but in his day, people in Britain were already starting to identify what we now recognize as dinosaurs. Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus became the basis for anatomist Richard Owen to name the group “Dinosauria” in 1841 and over the course of the 1800s, researchers in Europe and America and eventually around the world would increasingly add new genera to the group. The dinosaurs, it was clear, died out sometime in that odd Cretaceous-Tertiary gap, whether suddenly or gradually, depending on interpretation of the record. Without radiometric dating, there were no real dates on how old the Earth was or when these extinctions occurred. Noted British mathematical physicist William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (generally referred to as simply Lord Kelvin and whom the temperature scale is named after), pioneer in formulating the laws of thermodynamics and also a notable early critic of Charles Darwin’s ideas on evolution by natural selection, put forth an 1862 calculation in which he suggested the Earth was only about 100 million years old, an idea that held significant sway through near the end of the century. Nevertheless, the rock layers gave some indication of the ordering. In 1905, when Tyrannosaurus rex was discovered in Montana, USA and announced to the world in a New York Times article, the headline read “MINING FOR MAMMOTHS IN THE BAD LANDS; How the Monster Tyrannosaurus Rex Was Dug Out of His 8,000,000-Year-Old Tomb. Found in the Most Difficult and Inaccessible of fossil Quarries—Character and Habits of this Most Remarkable Prehistoric Beast.” The extinction of these grand creatures was generally waved vaguely at something like climate. The world had gotten colder and a superior group, the mammals, had taken their place and adopted many grand forms. The prevailing view of dinosaurs as slow, cold-blooded, stupid beasts continued through most of the 1900s. They were impressive, yes, but ultimately not the equals of what came afterwards. The invention of radiometric dating in 1907, however, would at least begin to anchor events more firmly in time and rapidly expand the understood age of the Earth.

Starting in the late 1960s and really taking off in the 1970s, a period known as the dinosaur renaissance remade how we think about dinosaurs. Following especially the study of the dromaeosaur (“raptor”) Deinonychus antirrhopus, paradigms shifted to seeing dinosaurs more like birds and less like the traditional conception of reptiles (today of course, it is firmly understood in cladistics that birds are dinosaurs and therefore reptiles). The new dinosaurs were fast-moving and warm-blooded, easily the physiological equals of modern mammals and birds. This raised doubts as to the idea that the non-avian dinosaurs’ days coming to an end could be explained with a gesture to mammals’ supposedly superior ability to adapt to change. There remained resistance however to the idea that something catastrophic rather than gradualistic had occurred.

Then in 1980, father-and-son team Luis and Walter Alvarez, a physicist and geologist respectively, proposed what soon became known as the “Alvarez hypothesis” and what is most likely the story for the K-Pg extinction you know and believe. They noted that at several sampling sites, there was a notable spike in trace iridium in sediment layers at the K-Pg boundary. Iridium, element 77, is exceedingly rare on the surface of Earth but more commonly associated with asteroids. The reason for this is the differentiation by density that occurred during and following the accretion processes in the early Solar System. On Earth, heavy elements like iridium sank deep into the center of the early molten planet while there was less of an impetus for this in smaller bodies. As such, now asteroid impacts can sometimes be associated with higher amounts of trace iridium than are usually otherwise geologically present. A global iridium layer at the K-Pg boundary would be suggestive of an impact event and, indeed, it seems that the Alvarezes had identified exactly that signature. Within academia, this paradigm struggled hard to find acceptance and if you have further interest and two hours to spare, please, when you finish reading this article, watch Oliver Lugg’s YouTube video The Mass Extinction Debates: A Science Communication Odyssey, which I consider to be one of the best commentaries on science and science communication I’ve ever encountered. Whatever the case, over the following decade, the scientific consensus gradually moved to accept the asteroid impact. It was hard-confirmed with publication demonstrating the existence of an impact crater at the K-T boundary in 1991. Today, in relevant fields it is universally accepted that a catastrophic impact occurred at the site of Chicxulub, Mexico on the Yucatán Peninsula 66 million years ago. A vast majority of relevant experts also agree that this was the primary cause for the mass extinction that occurred at that boundary. We will now explore the story that scientists have put together for what this was like. More than three decades of research, extensive computer modeling, and study of the topology of the impact site and other geological layers from the same time have allowed reconstruction to paint a much more detailed picture than the more primordial impact events I mentioned.

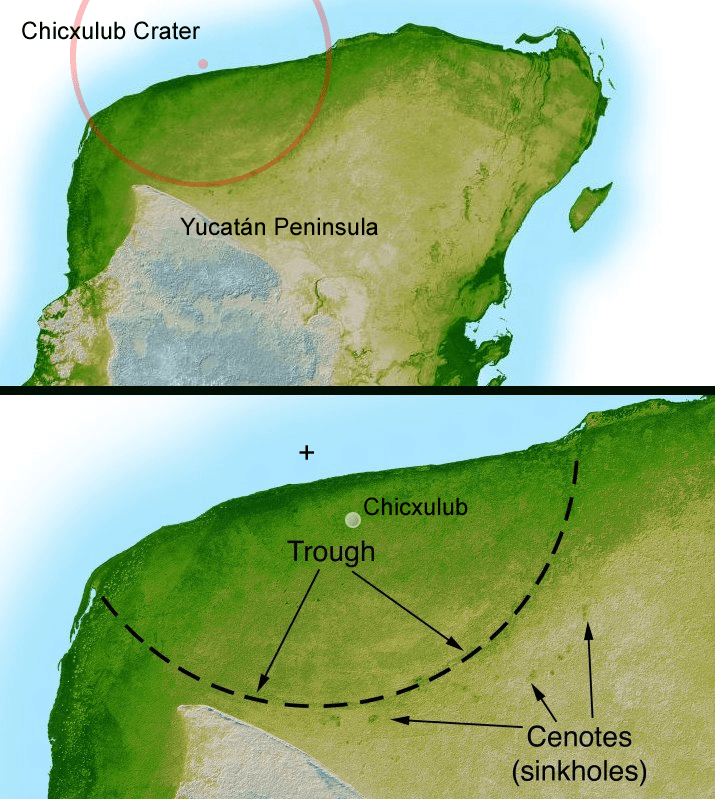

A map of the Chicxulub Crater today from NASA. The crater is located in the Mexican state of Yucatán. For those who’ve already been reading this blog, this region may stand out to you as important in the history of the Maya civilization. The important Postclassic cities of Uxmal and Chichén Itzá are just outside the crater area to the south and east respectively. The cenotes or sinkholes created by the impact-derived geography of the region were often sacred sites in Maya religion in the area.

Returning to the Late Cretaceous, it’s a normal day like any other when the asteroid (some older publications will suggest it was a comet but extensive study now tends to agree the material signature is mostly consistent with an asteroid), comes in the direction of Earth, preparing for impact. It’s not possible to reconstruct exactly the chain of events in the Solar System that led to the object finding its way to Earth at this time, but it likely came from beyond the orbit of Jupiter as a highly eccentric and novel visitor to the inner planets. Whatever the case, it found itself falling in Earth’s gravity. Our planet’s atmosphere is a chaotic sea of gases that gets thinner and thinner as one gets higher up with most of its mass within the bottom 11 kilometers or so of the surface but with gas extending out some 100 kilometers towards space. The asteroid traveled around 18 kilometers a second relative to the ground, meaning that it would clear the distance between space and ground within less than 6 seconds. In that time, friction with the atmosphere would create immense heat and the object would outshine the Sun by orders of magnitude for anyone within sight of it. Impact happened at an angle of between 45 and 60 degrees from the horizontal and the object was moving southwest. Measuring in at around 10 kilometers in diameter, the asteroid would have been similar in size to Mount Everest today. At the moment of impact, the horror was just beginning.

The energy release was the 300 zettajoules (that’s 3*1023 Joules for those who are not up on their ISO unit prefixes) that I mentioned in my opening Quetzalcoatlus story (a different source I’ve been using gave 100 zettajoules so keep in mind that while the order of magnitude here is relatively consistent, the energy release could be several times larger or smaller depending on your source). For context, the science YouTube channel Kurzgesagt (their source document here) once did a video in which they calculated what would happen if every nuclear bomb currently on Earth was detonated together at once. Between an estimated 15,000 nuclear weapons and with a relatively typical payload being around the equivalent of 200,000 tons of TNT, they calculate that the explosive power of all the nukes together would be about 300 billion tons of TNT, give or take quite a bit. Converting to Joules for the sake of this blog’s metric preference and keeping our units equivalent, the number you get is about 1.2552*1019 Joules. That is .012552 zettajoules. 300/.012252 is 24485.798237 on my calculator. So using this estimate for the global nuclear payload and the Chicxulub impact energy, we come to a conclusion that the Chicxulub impactor released a relatively equivalent energy to modern humanity nuking itself with every bomb it has about 24,486 times at once. Keep in mind that both of our comparators here can go up and down by a lot depending on whom you ask but the staggering difference in magnitude is undeniable. This is the hell that was unleashed upon the Late Cretaceous world.

The quickest way to die by impact was by light, which converts to heat. Light travels at 299,792,458 meters per second, meaning that even in the seconds prior to impact, thermal radiation from the superheated object in the atmosphere was being emitted at deadly intensities for those close enough. Potentially up to 1,500 kilometers from impact, biological material would have simply ignited instantly. Plants, animals, and other organisms within this area covering much of southern North America died intensely and all at once, missing out, probably gracefully, on what was to follow. The asteroid’s impact site was the ocean, on the continental shelf, and immediately it would have displaced all the water in the vicinity, its shockwave throwing back and vaporizing the ocean for kilometers. It then vaporized the local crust of the Earth, causing it to splash away from it with fluid motion. As the superheated material became effectively lighter than the ground around it, it pulled upwards at the center of the impact site, making a short-lived mountain in the middle of it. (Movement of superheated air and ground upwards in the wake of a huge explosion is a well-observed phenomenon and is, for example, one of the reasons that nuclear bombs make mushroom clouds.) This molten mountain would have soon collapsed, sending a secondary burst of energy into the returning boiling oceans around the impact site. Research at the Chicxulub Crater has revealed around 130 meters deep of breccia (rock matrix composed of shattered minerals) at the site, which all would have rapidly been created as the local crust was vaporized and much of it then cooled and crystallized in the air before falling back down as the chaos subsided within tens of minutes. (Of course, most of the material thrown up went much further, but we’ll get to this.)

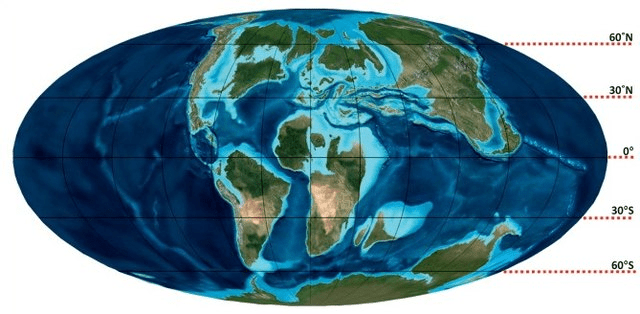

The layout of the continents as they appeared in the Late Cretaceous Period from Mannion, 2013. My usual source of available images, Wikimedia Commons, appears to be missing any maps relating to the Maastrichtian Age of the Late Cretaceous Period from 72.1 to 66 million years ago when this story takes place. So for your information, the map above relates actually to the Santonian Age from 86.3 to 83.6 million years ago. You are welcome to be angry about this in the comments.

The Chicxulub Crater is a very large geological feature which has been subject to much research since its study. However, focus on the impact site itself risks missing the macro-drama that played out across the planet in the next minutes and hours. On most of the planet that was not in line of sight of the apocalyptic flash of light, the first sign of Judgement Day was the pouring out of the Seventh Bowl. Normally, earthquake magnitudes are measured on the Richter scale, a logarithmic scale where going up by 1 indicates a tenfold increase in energy release. The largest earthquake ever recorded by modern science was the Great Chilean Earthquake of 1960 which measured around a 9.5 on the scale. This is around the maximum energy release which the system of plate tectonics can physically produce. But an asteroid impact does not come with the same limitations. Some estimates place the earthquake created by the Chicxulub impact somewhere around category 11, large enough to be felt globally and quite probably the most significant earthquake since the evolution of animal life. A shockwave moving at the speed of sound would have toppled rocks and broken the ground, felled forests of trees, and injured large dinosaurs that could not stay on their feet. The double whammy was that since the impact site was in the ocean, similar energy was imparted onto the seawater, firing off a ring of tsunamis kilometers tall that would have pounded into the world’s shores over the course of the coming several days, drowning entire ecosystems. Especially as the Atlantic was still much thinner at this point, many of the world’s continents were not too far away. And let us not forget about air displacement as well. As the asteroid entered the atmosphere, it began the process of heating air to phenomenal temperatures. Hot air expands and expansion from a central point means a circle of pressure pushing outwards. For air, this means fast hot winds. Colossal storm systems comparable to those on the gas giants of our Solar System ripped across the planet, unleashing hurricanes the likes of which the planet has only seen in similarly catastrophic events like the End-Permian Extinction. Storm systems on Earth are largely driven by differentials in temperature in parts of the air. And another aspect of the impact was about to inject quite a bit of heat around the planet.

Isaac Newton’s Third Law of Motion, as written in 1687 in the Principia, states, “To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction; or the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.” When the asteroid made contact, its immense force was followed by the immense movement of material upwards. This impact ejecta likely totaled several times the mass of the asteroid. Different models will use different numbers and here I am not going to get too bogged down with them as the general narrative of what happened is relatively uncontroversial. A splash of molten material shot upwards in all directions hundreds of kilometers into space. Depending on the time of day this happened, the sunlight glinting off the ejecta may have been a bright optical spectacle like the tail of a comet but orders of magnitude larger. For some lucky objects in this ejecta, this cataclysm would have been their ticket out of the gravity well of the Earth altogether, much as similar impacts have thrust prehistoric Mars rocks into the cosmos to fall into our planet as Martian meteorites. But for most of the material, any time in orbit was very temporary and it would come right back down. As the molten material careened back towards the planet, it got superheated a second time in the atmosphere, dropping meteors of varying sizes across the planet. The large amount of superheated materials in the sky would have rapidly heated the atmosphere of the Earth, sending global temperatures spiking up to dangerous levels, like the inside of an oven. Large animals not insulated by burrows or water may have died en masse, even if not hit by molten debris, which was also a concern. On top of this, any vegetation became kindling for fires, which in the coming days would have raged across the landscape, turning forests into death traps. At first, animals further from the impact site would have met milder conditions but as the Earth continued spinning under the plume of ejecta, this would have stopped mattering over the course of the day. It is difficult to say what proportion of the dinosaurs died in the first day after the impact, but I am inclined to believe it was very high.

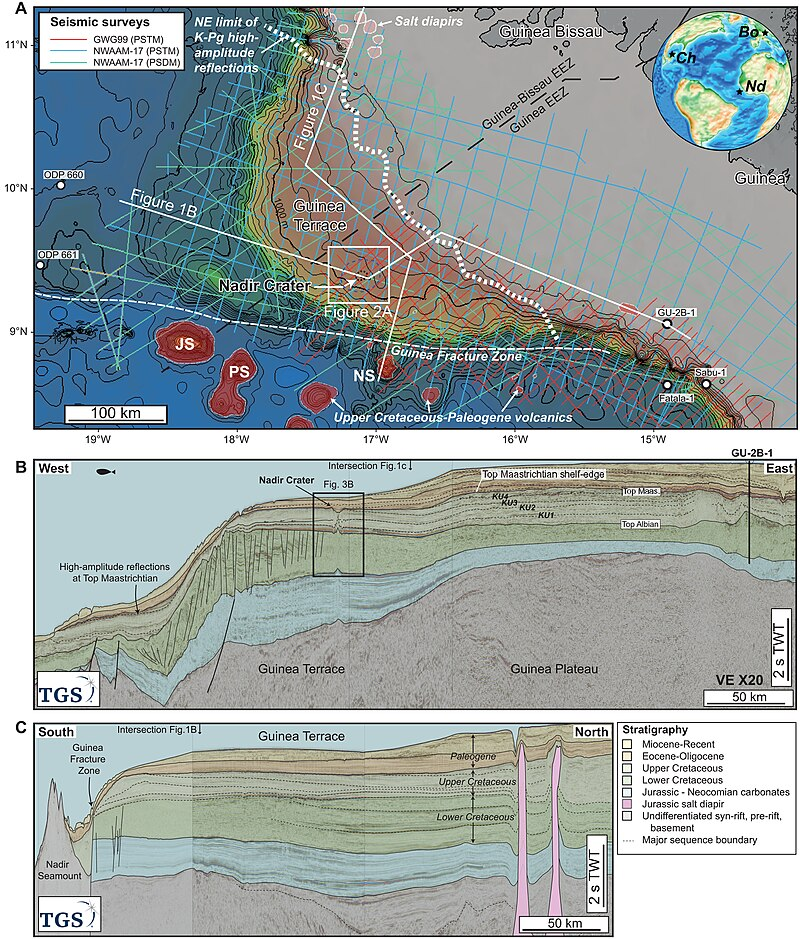

Cross-section of Nadir Crater and the surrounding crust, located off the coast of Guinea and Guinea-Bissau in West Africa. This is from a paper by Nicholson et al. in 2022 arguing that the crater represents an additional impact structure from the K-Pg boundary.

If you’ve been following research on this subject in recent years, you may briefly recall an interesting tidbit: the increasing recognition of a possible second crater. I have seen some science communicators trivialize this as “two asteroids” which makes it sound wildly improbable but it is consistent with some things we know about extraterrestrial impacts. The place of importance is Nadir Crater, located off the shore of West Africa near the shared border of the modern nation-states of Guinea and Guinea-Bissau. Here on the continental shelf, buried in sediment at the K-Pg boundary, lies a probable crater some 8.5 kilometers in diameter which seems to have been created by an object around 400 meters in diameter (which is of course not even close in size to the one that hit at Chicxulub). At the end of the Cretaceous, the Atlantic was much thinner than today so the Nadir and Chicxulub impact sites would have been around 5,500 kilometers apart instead of the modern 8,000 kilometers. Therefore, there are two major likely explanations for the evidence. Perhaps the Nadir object had been a smaller body in orbit around the Chicxulub object (some large objects in the Asteroid Belt do have small natural satellites such as 243 Ida with its moon Dactyl) or alternatively it may have been a piece of the Chicxulub impactor that broke off as it passed through the Earth’s Roche limit and began to be pulled apart by the planet’s gravity. (Recall earlier when I discussed the Permian impact of the East Warburton Basin, where two sites seem to have been impact epicenters, suggesting that impactor broke apart on entry.) This site is just one that has been identified and it is not impossible at all that similar asteroid moons or fragments fell in different places as well.

Whatever the case, gawking at the destructive details was not something that the organisms alive 66 million years ago had the opportunity to do. In the wake of that hellish day, the Earth was a very different place. When the fires cooled and the waves and winds calmed, they did so over a darkening Earth. Like a nuclear winter on steroids, the asteroid filled the atmosphere with particles that decreased sunlight reaching the surface. Global temperatures may have dropped by tens of degrees on average in the following years, a deadly climate shock for temperature-sensitive organisms. The decrease in sunlight hit plants and photosynthetic algae especially and the photosynthesis that underlies the planet’s macroorganism food chains largely stopped. The result was that herbivores then found little to eat and themselves starved. Carnivores that fed on them would have been able to scavenge for some time, but decomposition would then bring their own turn with starvation. For the few megafauna that made it through the opening natural disasters, the trophic collapse would have made survival impossible in the following years. It seems of all the land animals that survived, none of them were megafauna. Like a cruel joke, as the sky cleared and the ice thawed, temperatures would swing in the other direction with runaway global warming as massive amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases released from the crust during impact would absorb solar energy and send temperatures careening in the other direction.

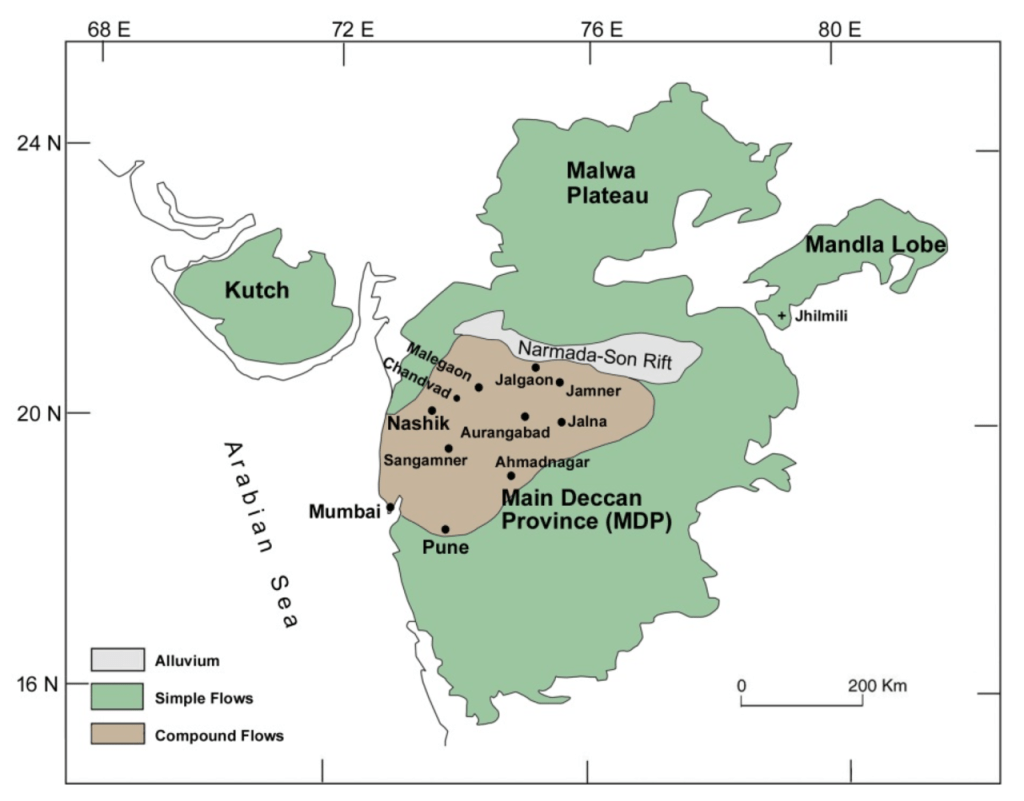

This is a map of the rock formation known as the Deccan Traps in India, from Götze et al., 2020. This represents the distribution of the igneous rock as it exists today. The Deccan eruptions almost certainly covered a larger area that has been shrunk to some degree by later geological processes.

It is here that I am obligated to bring up another interesting aspect to the story, the Deccan Traps, another K-Pg boundary phenomenon in the west-central Indian Subcontinent. Geologically speaking, the Deccan Traps are what is called a large igneous province (or LIP), a vast region formed of igneous rock, partly covered and partly exposed. They reveal that at the end of the Cretaceous and the opening of the Paleogene, several periods of intense eruption covered much of the Indian Subcontinent (then actually a separate continent in the middle of the Tethys Ocean) in lava, between 67.5 and 60.5 million years ago. It appears to have happened in three major phases, each time with potentially hundreds of thousands of years of active volcanic activity. One of these phases seems to have occurred before the Chicxulub impact and two after. It’s unclear exactly if the lava was flowing out when the impactor hit on the other side of the world, though some scientists wonder if the seismic shockwaves sent by the impactor may have excited and intensified volcanism for a period of time. For a long time, the Deccan eruptions were considered an alternative possible explanation for the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs and the other victims of the K-Pg mass-extinction. The occurrence of very long-term volcanic eruptions would have released huge amounts of greenhouse gases that would have affected global temperatures and encouraged acid rain, stressing ecosystems. As the Alvarez hypothesis has been better and better vindicated by global patterns of evidence, the Deccan Traps have come to be discussed less commonly as an alternative but as an interesting independent factor. Perhaps before the space rock brought the wrath of the gods from the sky, the gods from the underworld had already put global ecosystems in a fragile state. Every article written on this blog is made with the hope that some readers will discover tangential topics that invite new explorations of exciting topics. If you like catastrophic extinction events, I recommend exploring Earth’s history of volcanism next.

It is estimated that around 75% of species went extinct in the K-Pg extinction event. Most famously this included every non-avian dinosaur species. I say “non-avian” because one clade of dinosaurs, the birds, did continue and even thrive today. (Thanks to the birds, there are technically more living dinosaur species than there are living mammal species!) The dinosaurs’ aerial relatives the pterosaurs were another casualty as were various groups of marine reptiles, including the plesiosaurs and mosasaurs. The ammonites, shelled cephalopod mollusks that were numerous enough that they provide amazing index fossils from the Devonian to the Cretaceous, disappear from the fossil record at the boundary. Even in groups that made it through such as mammals, heavy losses occurred with some lineages snuffed out entirely, deprived of the Cenozoic world where some of their relatives would take over the planet. Gradually food webs would be rebuilt. Seeds are a hardy biological power move that allowed plants to start germinating years after the impact as the skies began to clear and the survivors would eek out new orders to survive and diversify. In the coming chapters of the story of Earth, the mammals would take the roles of the dinosaurs and diversify into numerous different forms. The Cenozoic had begun. In the Paleogene period that followed impact, a new lineage of arboreal eutherian mammals would distinguish itself in tropical treetops. In tens of millions of years, the descendants of these animals, the primates, would have the intelligence to put together what happened on that day 66 million years ago. But before doing that, they would have an epic history of learning about objects in space.

Impactors and Us

It is the middle of the Holocene Epoch of the Quaternary Period in the northeast of the continent of Africa, around 3200 BC. Members of the social species Homo sapiens have formed communities around the Nile River where they manage the growth of cereal grains which provide for food in the fertile soil of the local river valley. In recent centuries, this combination of managed vegetation landscapes and sedentism has led to a population explosion. What I am describing of course is the late Neolithic culture that will soon become what history remembers as ancient Egypt. This is the Naqada III period in Egyptian archaeological chronology, sometimes called the “Protodynastic Period,” when local rulers are establishing small states but Egypt remains still disunified. The names of some of these local kings (about whom we individually know essentially nothing) will, in our time, comprise the oldest written names of human individuals known in the world. Narmer will become the first pharaoh of Egypt within the coming century and start a rulership legacy that will be remembered for thousands of years. But that time is not yet. Today at the community of Gerzeh (a modern site name) near the Faiyum Oasis, a body is being laid to rest. Around this individual’s neck is a beaded necklace, an indicator of some wealth and prestige, strung with beads of precious stones. Among these are lapis lazuli, gold, and carnelian. But a fourth type of precious stone is among them: meteoric iron.

Archaeologists identified these beads in two separate burials from the site of Gerzeh. Their association with other precious stones demonstrates that they were objects of high value and indeed similar prestige presence of meteoric iron in Egyptian burials would occur throughout the coming millennia, though the Gerzeh beads indicate the earliest appearance of this phenomenon yet documented. As a refresher, since I have gone through all of geological history since bringing this up, meteoric iron is a specific alloy of iron and nickel that formed in the early Solar System specifically in celestial bodies that were large enough to have their gravity and internal heat differentiate materials by density (congealing heavy metals at their centers) but which were then blown apart in collisions that slung out their core contents as iron-nickel asteroids. The Gerzeh beads date to a time in which copper-working had existed for several millennia and bronze was starting to enter use through the alloying of copper and tin. So meteoric iron was not the first metal to be worked, but it was surprisingly early. In fact, the Gerzeh beads appear around 2,000 years before the advent of the Iron Age in the Near East and Egypt.

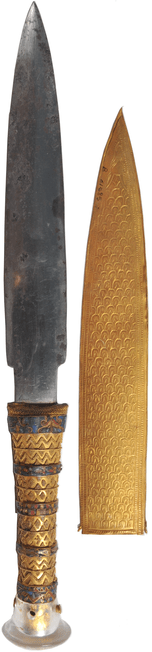

This is the dagger found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, a New Kingdom pharaoh who reigned over Egypt between 1332 and 1323 BC. The blade is made of meteoric iron and is a rare example of ironworking from Egypt’s Late Bronze Age.

The most famous artifact from ancient Egypt making use of meteoric iron was found as part of one of history’s most famous archaeological discoveries. During Egypt’s New Kingdom period (1570-1069 BC), the age of pharaonic pyramids had long ended and the most prominent burial practice for rulers was in the Valley of the Kings, a region across the Nile from Thebes, the most sacred city of Upper Egypt, where rock-cut tombs were packed with treasures for the departed to use in the afterlife. Most of these tombs were long raided and emptied of their treasure in antiquity, but in 1922 British archaeologist Howard Carter identified the presence of one that had been successfully kept untouched. Excavation took several years but in 1925, the mummy and sarcophagus of a pharaoh was finally brought back out of the tomb. Of course, thanks to plentiful tomb inscriptions and labeled grave goods, the identity of this figure was already known. Tutankhamun became pharaoh in 1332 BC at around the age of 8. His father had been Akhenaten, an extremely controversial pharaoh who had attempted to overturn Egypt’s traditional religion to focus worship on the single solar deity the Aten. Tutankhamun’s child reign had, probably at the influence of court officials who held the real power behind the boy, seen the restoration of the old gods to prominence. Around the age of 18 in 1323 BC, he died due to health complications, fated to become something of a footnote ruler in Egyptian history. That is, until his tomb was discovered as perhaps the most intact example of a pharaonic tomb interior in its full glory, complete with even a full chariot stuffed in sideways and a vibrantly painted interior. In Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus was found a dagger with an iron blade (rare for the Late Bronze Age as you might imagine) and a shiny golden sheath. Metallic tests confirmed that this blade is composed of around 89% iron and 11% nickel with trace copper: meteoric iron. A royal prestige weapon had been made out of precious stone that fell from space. Whereas iron smelting was a difficult process with extremely high heat demands that was not widespread, meteoric iron was already differentiated from rock and therefore did not require smelting in the same way, likely making it more accessible to Bronze Age toolmakers. Of course, it was also extremely rare so it only made its way into high-value objects. Some have even suggested that this use of meteoric iron helped to develop the technology that would lead to iron smelting and the advent of the Iron Age. If this hypothesis is correct, extraterrestrial impactors have a role in defining the technological progression that has been used for reconstructing chronologies in the ancient Near East for all of modern archaeological history.

Egypt was not the only formative civilization where meteoric iron played a role in the advent of new forms of metalworking. The earliest use of iron for tools in China comes from the period of the Shang Dynasty (around 1600 to 1046 BC), also generally considered part of its own region’s Bronze Age. And as a quick aside, if you have never taken the time to appreciate Shang metalworking, go to Google in another tab right now, type “Shang bronzes,” and go back to that when you’re done reading this. They’re spectacularly intricate. Axeheads from the Shang period are made of bronze but a few have been found on which meteoric iron has been hot-forged onto the sharp cutting edge of the blade to make it a little harder. Once again, the rarity of the material for these objects indicates they must certainly have been prestige items to some degree. While limited evidence makes it hard to know for sure, it seems likely that this forging of meteoric iron represents an independent regional invention in China. 1046 BC is the traditional date given for the fall of the Shang Dynasty to the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BC), when Wu of Zhou claimed that the Shang had lost the Mandate of Heaven and called for new rulership of China. The Zhou invested a lot of local power in quasi-feudal local rulers who over the course of the dynasty would become increasingly autonomous and even make open war on each other. One of these small domains was the state of Guo in what is now China’s province of Henan. At the site of Shangcunling, 234 human burials and 4 horse burials were discovered which bronze inscriptions associated with Guo. Five bronze-iron objects were found among these tombs and submitted to chemical analysis. Three of the five were made with meteoric iron while two had compositions more in line with smelted iron, a sign of a transitioning age. In 687 BC, Guo was conquered by the expansionist state of Qin (the same that some centuries down the line would reunify and centralize China), meaning that inscriptions associated with the former likely don’t date from after this. The later portion of the Zhou period saw the full advent of the Iron Age… and of course the Warring States Period when regional lords had ample time to use iron weapons against one another.

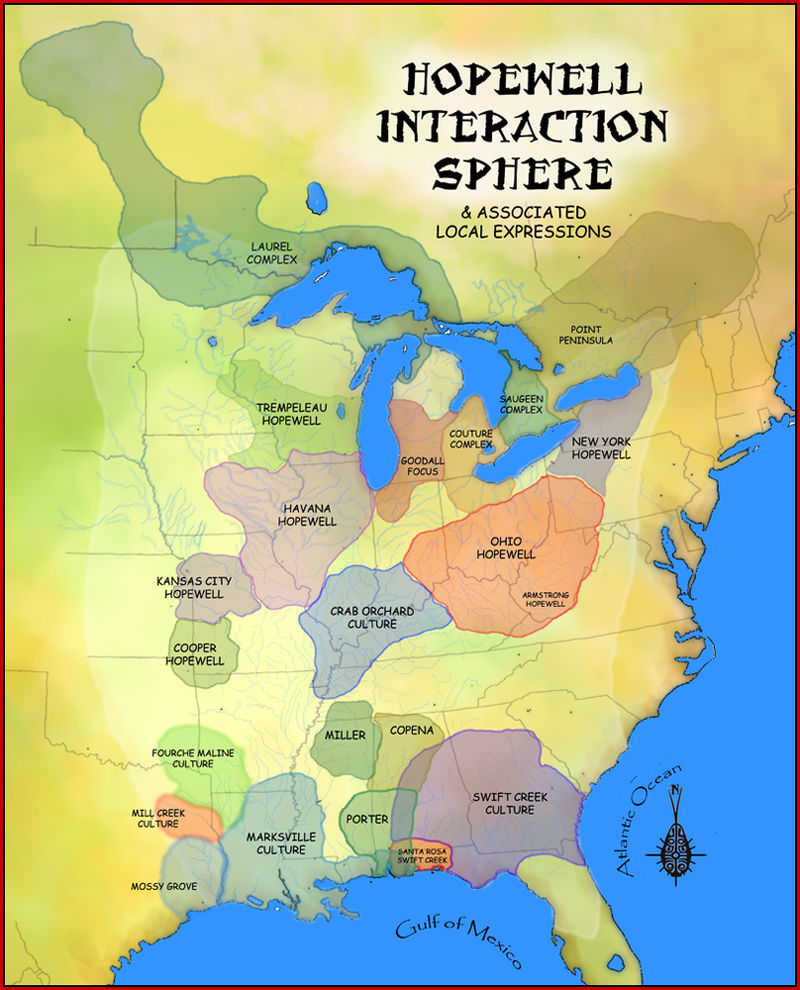

This map of the Hopewell interaction sphere in Eastern North America between around 100 BC and 500 AD by Wikimedia contributor Heironymous Rowe.