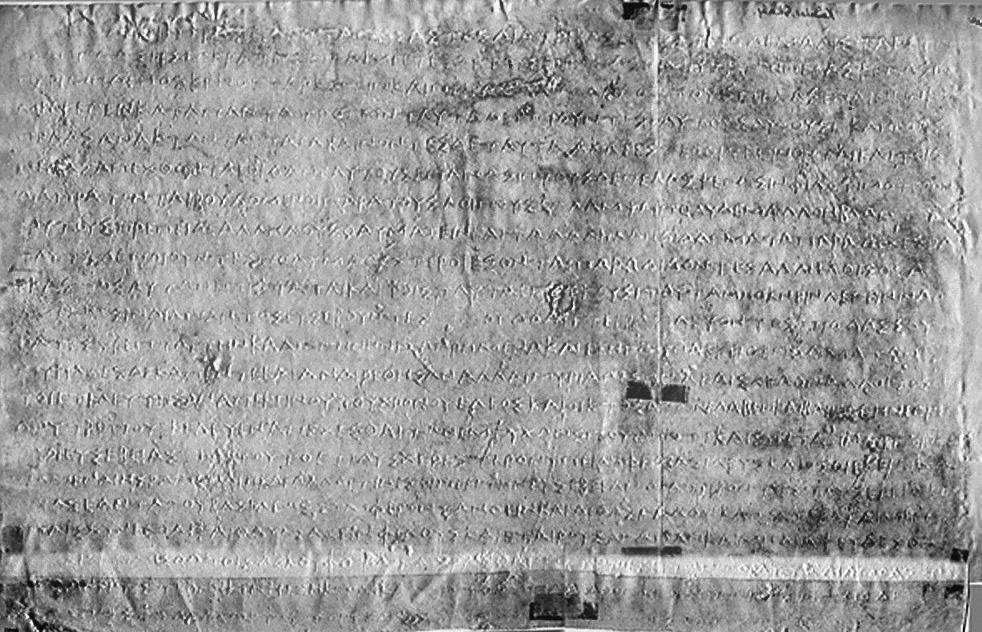

The following is what is titled by historians Major Rock Edict XIII of Ashoka, which was issued in 256 BC and inscribed in large stone inscriptions along with others in several places throughout the ancient Maurya Empire of India (traditionally 322 to 185 BC) under the reign of its third king Ashoka (ruled 268 to 232 BC), the first to convert to Buddhism. The edict is inscribed at multiple places in several languages (including the foreign languages Greek and Aramaic) but the version I quote here is from the inscription at Kalsi in the modern Indian state of Uttarakhand near Tibet. It is originally written in Prakrit, the vernacular dialectic continuum of Indo-Aryan languages in this period related to but distinct from standard Sanskrit and Pali, and the Brahmi script. This version is translated to English by Ven. S. Dhammika. The inscription refers to the deeds of Ashoka (under the name “Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi”) and his dedication to the Dhamma (Prakrit and Pali rendering of Sanskrit “Dharma,” the teachings of the Buddha), referring along the way to various peoples of the world.

Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, conquered the Kalingas eight years after his coronation. One hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand were killed and many more died (from other causes). After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods came to feel a strong inclination towards the Dhamma, a love for the Dhamma and for instruction in Dhamma. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas.

Indeed, Beloved-of-the-Gods is deeply pained by the killing, dying and deportation that take place when an unconquered country is conquered. But Beloved-of-the-Gods is pained even more by this — that Brahmans, ascetics, and householders of different religions who live in those countries, and who are respectful to superiors, to mother and father, to elders, and who behave properly and have strong loyalty towards friends, acquaintances, companions, relatives, servants and employees — that they are injured, killed or separated from their loved ones. Even those who are not affected (by all this) suffer when they see friends, acquaintances, companions and relatives affected. These misfortunes befall all (as a result of war), and this pains Beloved-of-the-gods.

There is no country, except among the Greeks, where these two groups, Brahmans and ascetics, are not found, and there is no country where people are not devoted to one or another religion. Therefore the killing, death or deportation of a hundredth, or even a thousandth part of those who died during the conquest of Kalinga now pains Beloved-of-the-Gods. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods thinks that even those who do wrong should be forgiven where forgiveness is possible.

Even the forest people, who live in Beloved-of-the-Gods’ domain, are entreated and reasoned with to act properly. They are told that despite his remorse Beloved-of-the-Gods has the power to punish them if necessary, so that they should be ashamed of their wrong and not be killed. Truly, Beloved-of-the-Gods desires non-injury, restraint and impartiality to all beings, even where wrong has been done.

Now it is conquest by Dhamma that Beloved-of-the-Gods considers to be the best conquest. And it (conquest by Dhamma) has been won here, on the borders, even six hundred yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni. Here in the king’s domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods’ instructions in Dhamma. Even where Beloved-of-the-Gods’ envoys have not been, these people too, having heard of the practice of Dhamma and the ordinances and instructions in Dhamma given by Beloved-of-the-Gods, are following it and will continue to do so. This conquest has been won everywhere, and it gives great joy — the joy which only conquest by Dhamma can give. But even this joy is of little consequence. Beloved-of-the-Gods considers the great fruit to be experienced in the next world to be more important.

I have had this Dhamma edict written so that my sons and great-grandsons may not consider making new conquests, or that if military conquests are made, that they be done with forbearance and light punishment, or better still, that they consider making conquest by Dhamma only, for that bears fruit in this world and the next. May all their intense devotion be given to this which has a result in this world and the next.

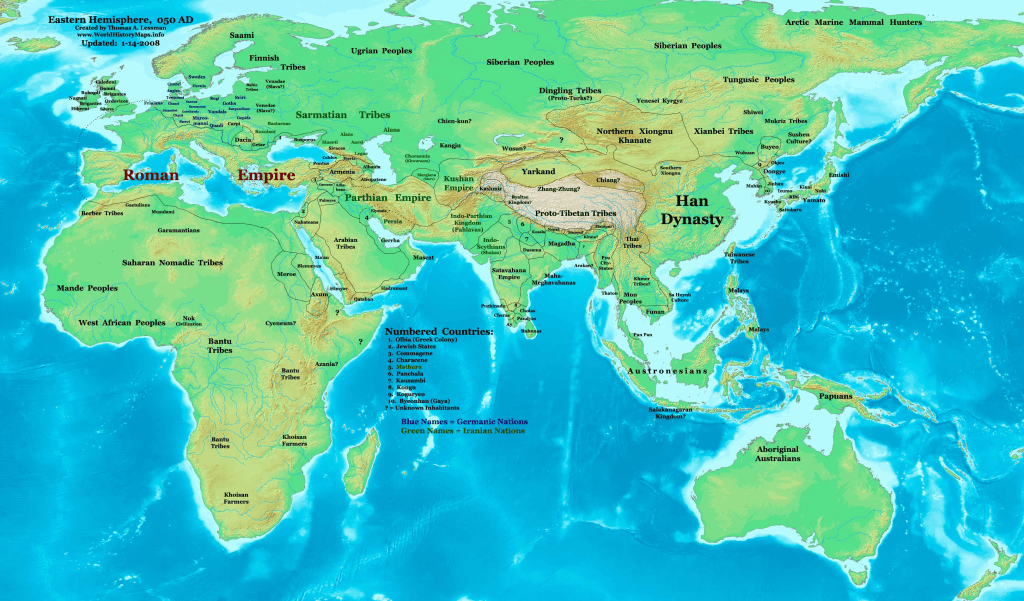

An Indian king embracing a new ideology and spreading it far and wide, all while referring to Greeks among the peoples both in his kingdom and abroad? The classical world (which this article will define simply as the world between about 800 BC and 500 AD) was a time of extensive interchange among the cultures of Eurasia and North Africa when the more regional civilizations of earlier periods increasingly came into economic, cultural, and military contact with one another. Empires reached new unprecedented scales and shared ideologies began to be expressed over even larger stretches of the planet. The story I will express here is one way to tell the events of Eurasia of the five centuries or so before the time of Jesus, focusing on two large international cultural movements that weaved together large areas of the world while also weaving together with each other: Buddhism and Hellenism. In doing so, we will explore internationalism in the classical world.

The Cradle of Buddhism

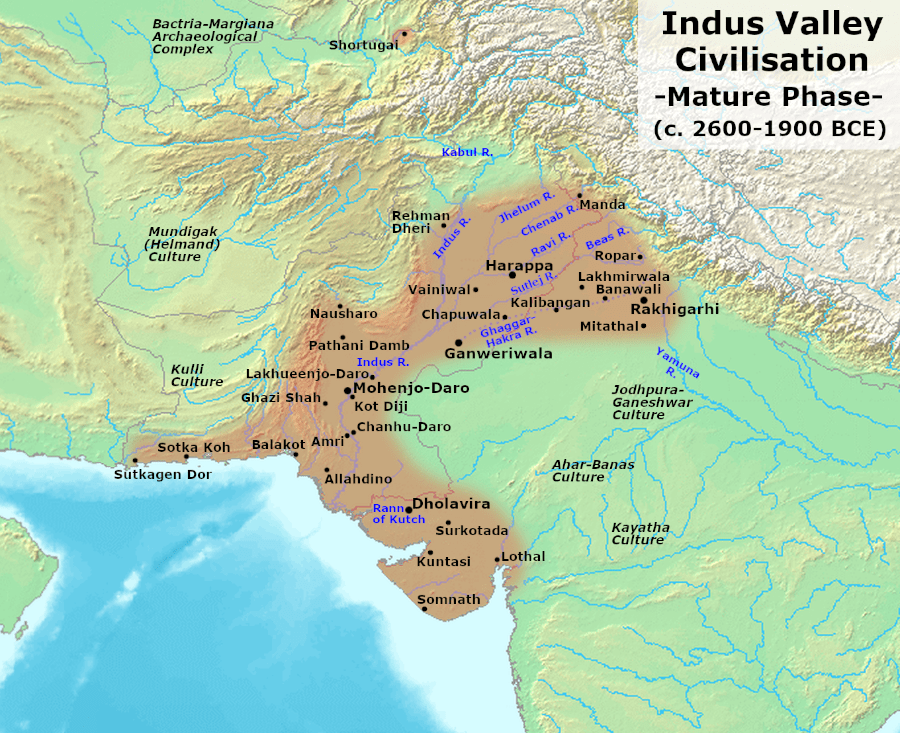

A map of the Indus Valley civilization at its height by Wikimedia contributor Avantiputra7.

In exploring the story we are going to tell, we should start with ancient India. The Indian Subcontinent has been home to complex urban civilizations since around 3300 BC when the Indus Valley civilization, also known as the Harappan civilization, began to develop in the northwest corner of the region. This civilization itself participated in long-range interactions, trading carnelian mined in what is now Pakistan with the world of the ancient Near East via the Persian Gulf. The script that the Harappans used has never been deciphered but the civilization does come into our known historical records by way of interactions with the Akkadian Empire (2334-2154 BC) and Third Dynasty of Ur (2112-2004 BC) of Mesopotamia, where it is referred to in Akkadian as Meluhha, a distant source of maritime trade and tribute. Harappan seals have been found as far as modern Syria, showing that here in the Middle Bronze Age, trade routes were already extensive. But the Indus Valley civilization was, as all civilizations are, a temporary fixture in its part of the world, declining after 1900 BC and its urban centers all abandoned after 1300 BC. Early archaeologists imagined they were destroyed by Aryan invaders but modern researchers suggest these developments had more to do with climatic changes affecting arable land in the alluvial floodplains of the Indus Valley and its tributaries. Since the linguistic, religious, and political nature of this civilization is not particularly well-understood, debates in both archaeology and the generally less-than-scientific nationalistic discourse of Pakistan and India continue, but for our purposes it was the millennium after the Harappans that was truly important for the context Buddhism emerged from.

Before I continue, a brief note. Prior to the conquest of the Indian Subcontinent by the British East India Company in the 1700s and 1800s AD, the subcontinent had never actually been completely politically unified. Even those empires which came close, the Maurya (traditionally 322-185 BC) and Mughal (1526-1857 AD) empires, both centered in the Indo-Gangetic Plain in the north, never subdued the very southern extremity of modern India. The Indian Subcontinent is a region about half the size of Europe with comparable cultural diversity. As such, almost any period-specific description of one “Indian culture” is doing some heavily misleading oversimplification. The further you dig into the topic of ancient India, the more this problem becomes apparent and just within preliminary research for this article, I realized that a lot of the things I thought about the topic were simplifications. As such, the approach I take here will try to accommodate more of the nuance but keep in mind that it too is glossing over some internal complexities. As always, I encourage further reading into the topic for anyone who is curious about it, even if you think you already have a general grasp of it from school or similar.

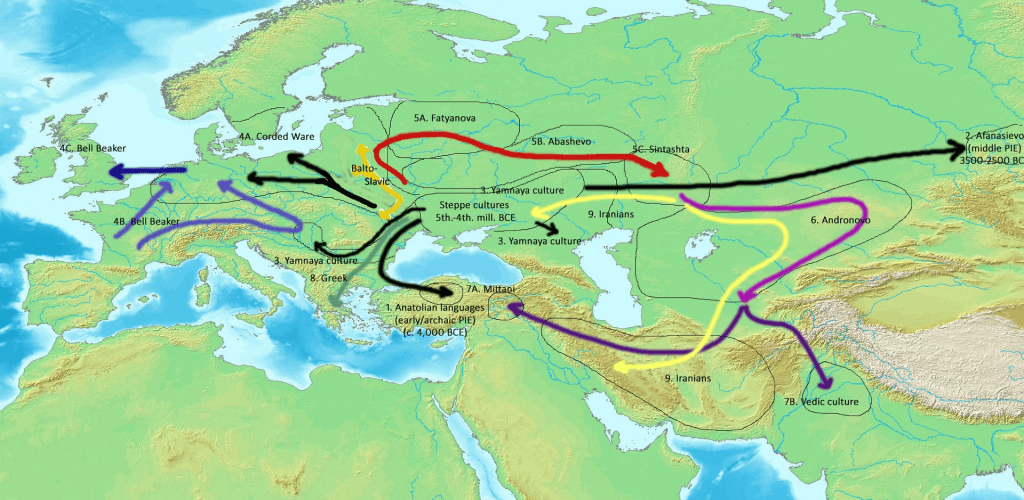

A map by Wikimedia contributor Joshua Jonathan displaying the Indo-European expansion between around 4000 and 1000 BC. The Indo-Aryan peoples were part of the eastern branch of this linguistic expansion, closely related to the Iranian peoples.

In the wake of the Indus Valley civilization, the Indian Subcontinent lacked significant urbanism but did continue to practice widespread agriculture. One language family that was particularly prominent on the subcontinent was the Dravidian languages, which today includes the likes of Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, and Kannada. In the northeast of India, an extension of the Austroasiatic (a language family mostly found in Southeast Asia which today includes the likes of Vietnamese and Khmer) languages known as the Munda languages were established from an early date, possibly as early as 2000 BC. But the most famous linguistic development of ancient India was the coming of Indo-European languages, specifically the Indo-Aryan branch, by 1500 BC. The Indo-European languages originated on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe around modern Ukraine more than 6,000 years ago. It used to be imagined fancifully that the Indo-European languages were spread in a conquest by which Indo-European-speaking peoples came to dominate or eliminate earlier peoples. This is not backed up by the archaeological record. Instead, these expansions largely occurred due to migrations of people who then mixed with local people groups, propagating certain elements of culture to them. For many readers, the term “Aryan” may raise alarm bells because of how it was appropriated by Europeans in the 1800s who promoted a racist pseudohistory that involved a superior white race expanding throughout the ancient world and bringing civilization, an idea explicitly endorsed at the state level by Nazi Germany in the next century. But in real history, the Indo-Aryans were simply an eastern branch of Indo-European speakers, present largely in what is now Iran and the Indian Subcontinent. After 1000 BC, speakers of these languages became prominent across the Indo-Gangetic Plain of the northern part of the subcontinent.

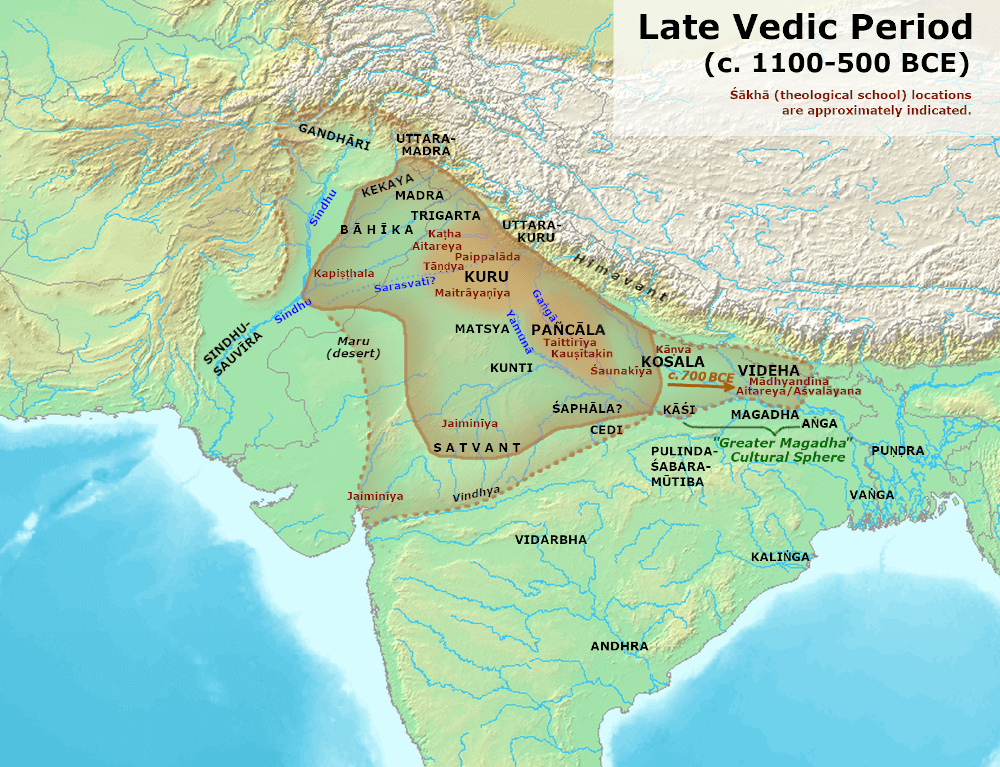

A map of states and groups in the Vedic period of northern India by Wikimedia contributor Avantiputra7.

Indian history as we can read it by local written traditions begins with the Vedic period, generally considered to have lasted from around 1500 to 500 BC. Strictly speaking, no known textual manuscripts have been found from this period but textual scholars of the Vedas, which comprise the oldest extant scriptures of what would become Hinduism, agree they were standardized from oral tradition over the course of this period. The language of the Vedas is Vedic Sanskrit, an Indo-Aryan language which is ancestral to many modern North Indian languages such as Hindi (the “Vedic” descriptor is a periodization which gives way to Classical Sanskrit in the middle of the first millennium BC, sort of like the transition between Classical and Late Latin that enjoyers of European linguistic history may be familiar with). Over the course of the Vedic period, the Indo-Gangetic Plain accumulated a number of centralized states with varying systems of government from kingdoms to republics. Sanskrit became a religious and prestige language of widespread importance, but an array of Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, and other languages were spoken throughout the region, all impacting each other as well. If you’ve learned about the Vedic period before, it likely centered on the formation of India’s caste system. The Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas which is considered to have been composed somewhere between 1500 and 1000 BC, refers to a caste system being in place in the Purusha Sutka. It tells how the primordial being Purusha divided his body into different portions which became four primary social castes or varnas: the brahmins (priestly caste), the kshatriyas (warrior and government caste), the vaishyas (tradespeople), and the shudras (laborers). However, in researching this, I was surprised to learn that the role of caste in the Vedic period is actually heavily debated and passages like the Purusha Sutka may be late inserts which became more useful for elites in the time of empires when Indian states were more centralized and eventually transitioned towards feudalism in late antiquity. As Ashoka referenced in the passage I opened this article with, there was certainly a caste system by the time extant inscriptions are written in the classical period, but before that is spottier. Historians used to refer to the religion of the Vedic period as “Brahmanism” and imagined it as making for a strict caste-separated society overseen by very powerful brahmins who held sway across much of India. This is what I learned in school and likely what your local school curricula assume. But more recent paradigms instead emphasize the constellation of local variations of religion that existed beside and overlapping with each other with caste structures that were likely present in some form but not as rigid and uniform as in later Indian history.

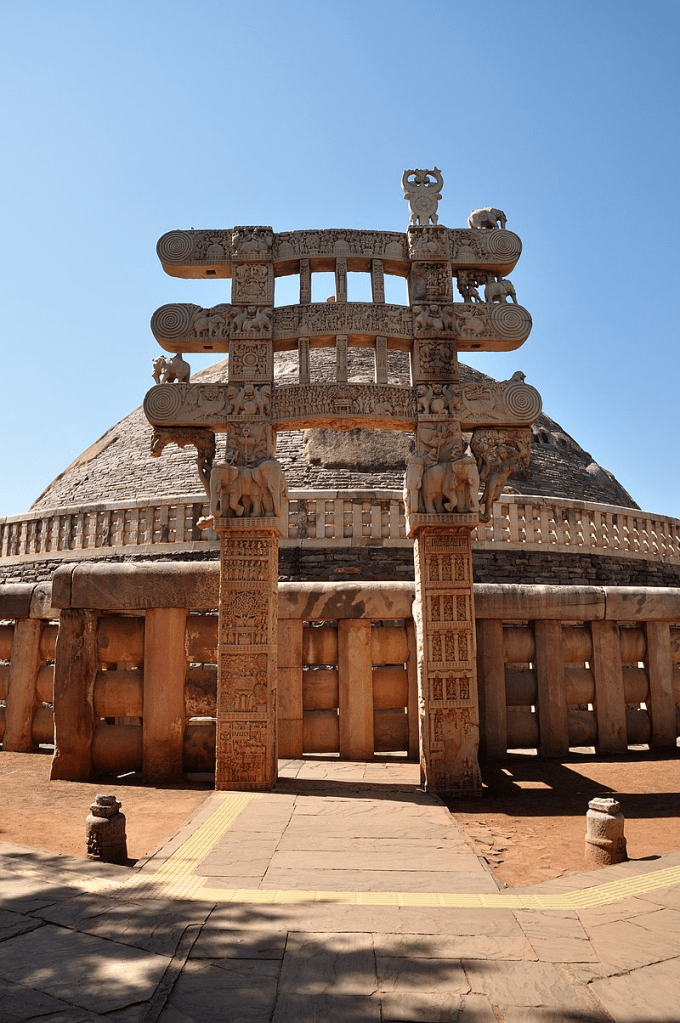

The Great Stupa at Sanchi, located in what is now the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, is one of the oldest examples of Buddhist architecture in the world, with construction having begun in the reign of Ashoka (268-232 BC). The decorative arch out front was constructed around two centuries later and shows several scenes from the traditional narrative of the life of the Buddha, though the Buddha himself is absent from the scenes of everything going on around him, represented for instance in one case by just a path where he is presumably walking. Scholars believe that early Buddhism may have been aniconic, opting not to display sacred figures directly (like modern Islam for example). Nevertheless, this provides an early example of a depiction of the traditional narrative of the Buddha’s life. Image by Wikimedia contributor Biswarup Ganguly.

Historians do not consider the traditional narrative of the life of the Buddha to be particularly historical and the details of his life, if he existed as an individual which most sources seem to find reasonable to assume, are obscure. Stories from his life appear in fragmented form in written sources and art from the 200s BC onwards, but it is not until the early 100s AD before a full biographical narrative on his life that we still have today was composed. This biography, the Buddhacharita, attributed to the Buddhist philosopher and playwright Ashvaghosha from Saketa (modern Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, India), dates to the early 100s AD and was composed in Classical Sanskrit. It is not known in its complete form in Sanskrit today but Chinese and Tibetan translations made a few centuries later complete the missing portions of the text. In this text and with details added by later biographies, the story of the Buddha became something like what follows.

Prior to his enlightenment, the one who would become the Buddha was named Siddhartha Gautama and some traditions date his birth to 563 BC and his death to 483 BC though there is not consensus on this even within Buddhist tradition and given dates can shift by about a century. Whatever the case, when he was to be born as a prince to royal parents of the Shakya clan in what is now northeastern India, various signs pointed to the child being exceptional in nature. Siddhartha’s father wanted to raise him as a great ruler and so kept him in the royal palace where his every whim was attended to. Sheltered in absolute luxury from the woes of the world, he was largely unaware of them until he ventured outside and saw what Buddhists call the Four Passing Sights: an old man, a sick man, a dead man, and a sramana or wandering holy man. These sights caused Siddhartha to wonder about the cause for dukkha (generally translated as “dissatisfaction” or “suffering”) and how it could be escaped. Taking inspiration from the sramana, he became a wandering ascetic, leaving the palace behind and foregoing material possessions, supposedly eating as little as a grain of rice a day. He nearly starved to death and decided that neither luxury nor extreme self-deprivation were productive in defeating dukkha, leading him to the Middle Way, the happy medium between the two. Taking up a meditation position under the Bodhi Tree (associated today with the site of Mahabodhi Temple in the Indian state of Bihar, where a tree supposedly descended from the original several generations down the line is still tended), he remained through a night of deep thought, during which he was harassed by the forces of the demon Mara, desperate to stop his enlightenment. Siddhartha emerged as the Buddha, the Enlightened One, understanding that dukkha comes from desire and that the way to eliminate the latter was to follow the Noble Eightfold Path. Enlightenment would lead to nirvana, liberation from samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth, and the Buddha made it his mission to lead others to the same victory. He started a religious community known as the sangha, which came to accept both men and women, and preached and performed miracles for the rest of his life. When he died, he left samsara but his legacy was carried on by a large group of disciples who preserved and propagated his teachings.

Since confidently compiling an objective secular biography of the historical Buddha is outside the scope of what can be done with extant sources, inquiries into the historical Buddha and the origins of Buddhism instead focus on reconstructing the world he would have lived in and asking what role the Buddhist movement would have played in that society. Historically, European historians understood early Buddhism to be a reaction against the strictures of Brahmanism which broke caste boundaries and questioned social orders. As the understanding of the religious landscape of ancient India has developed, this interpretation has become more difficult to uphold. When historians use the term “Brahmanism,” they imply the privileged religious position of the brahmin caste, but clues in the written geography of Classical Sanskrit texts seem to challenge the idea that this was universal across North India. The term “Aryavarta,” “Land of the Aryans,” is used as late as around 150 BC by the Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali to refer to the region that was part of the landscape of this social-religious institution, but this term does not seem to extend to places east of the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers (though the term gets expanded to more of North India in later centuries). The state that the historical Buddha would have lived in therefore, the Shakya Republic, a peripheral political entity located on what is now the Indian-Nepalese border, was outside this geographical distinction and in fact was not subject to the famous caste system. The state was a ganasangha, a term applied to aristocratic clan-based republics, and despite its dissimilarities with the “core” culture of Vedic India, it was in range to interact with them. All this to say that historical research no longer affirms the idea that Buddhism originated as a reaction against a sort of proto-Hinduism but rather that on the contrary Buddhism and Hinduism emerged from the local religious variation that took different forms in different parts of North India.

A map of the empire ruled by the Nanda Dynasty of Magadha at its height by Wikimedia contributor Avantiputra7.

The end of the Vedic period and opening of the classical world was a time of great political and religious experimentation in North India. A traditionally older contemporary of the Buddha, Mahavira, is even considered by Jains to be the twenty-fourth tirthankara, or supreme teacher of dharma, perhaps representing the historical beginnings of Jainism in the Kingdom of Magadha, not far from the Shakya Republic where Siddhartha came from. Magadha was one of a number of major centralized states in the northern part of the subcontinent which are referred to as the mahajanapadas in ancient Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain texts. In the later Vedic and early Classical period, these mahajanapadas were competing entities like any other region of the ancient world in which an array of small states played out complex geopolitics with one another. By the nature of our sources, it is difficult to know the exact political histories of any given one of these states but we are able to know that many of them were kingdoms, others small republics and tribal confederacies, and some even nascent empires that conquered or vassalized nearby states to expand their reach. In the 500s BC, Magadha began a phase of expansion in the area around its capital Pataliputra (modern day Patna in the Indian state of Bihar), building a centralized kingdom that was soon a regional power. Pataliputra became a thriving urban center which brought commerce from all across India while the fertile farmlands of the Ganges Valley produced ample wheat and famous garlic. In 345 BC, the Nanda Dynasty came to power, rapidly spreading the political influence of Magadha until it consumed almost all of the other mahajanapadas and nearly became North India’s first unifying empire. Imperial Indian history had begun and through the veins of empire Buddhism and Jainism, both lucky to have emerged near the imperial core, propagated. And then to the yet-unconquered west of the Nanda realm, in the Indus Valley, a new army entered the subcontinent in 327 BC, led by one of the most accomplished conquerors in the history of the world, addressing his men in Greek.

The Cradle of Hellenism

And now we turn our attention to the backstory of our other protagonists. Ancient Greek history has a lot of the same complexities of ancient Indian history. The region spent most of its history politically and culturally disunified and just about any generalization too broad will invariably not capture the realities of part of the Greek world at any particular time. Nevertheless, before we can discuss Greek influence, we need to do some exploration of how the Greeks saw themselves in aggregate. In this article, I will be using the problematic and imprecise term “Hellenism” to describe pan-Greek culture as well as the influence it had on other cultures. I am not referring to the art movement of recent centuries or the current neopagan religious movement, neither of which are really relevant to this article, even if they do take inspiration from ancient Greece. Our story, as it did with India, starts in the Bronze Age.

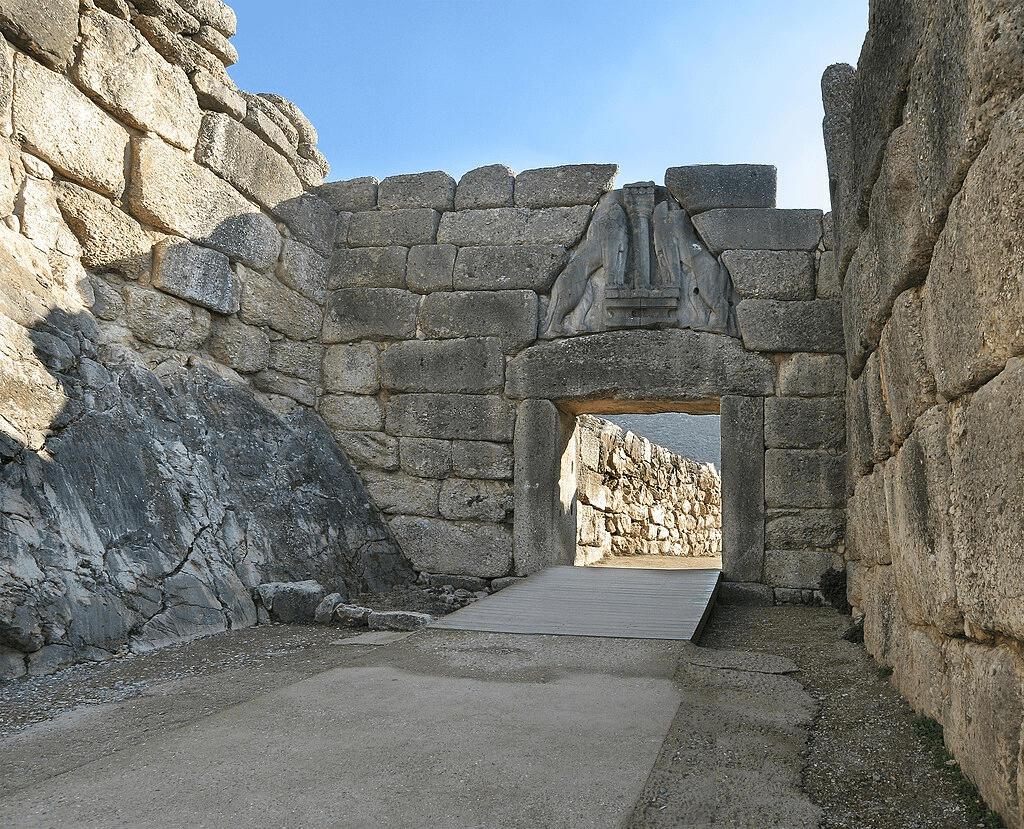

The Lion Gate at the citadel of Mycenae, erected in the Late Bronze Age around 1250 BC. Photo by Wikimedia contributor Andreas Trepte.

The first proto-civilizational developments in the Aegean world belong to the Cycladic culture, centered in the Cyclades Islands of the central Aegean Sea (that is, the likes of Naxos, Delos, Santorini, etc.) where Neolithic settlements cultivating olives and Near Eastern cereal grains like wheat and barley go back to around 5000 BC. Cycladic culture continued into the Bronze Age when it had an impact on the emerging Minoan culture of Crete which built some of the first large-scale “palatial” (though the actual palace status of structures like that at Knossos is somewhat controversial) complexes with surrounding urban centers in the Aegean world, starting after around 1925 BC. (You may have heard of the Minoan civilization being presented as having colonies including sites like the famous Cycladic archaeological site of Akrotiri on Santorini and that it was the first civilization of Europe. This is a combination of dated views and a disconnect between academic and popular sources. It is common for pop-history to gloss the Cycladic culture as part of the Minoan culture, which is actually primarily geographically limited to Crete. The directional arrow of development largely points to the Cyclades influencing the emergence of civilization on Crete more than the other way around.) The Minoans developed several different scripts including Linear A, Cretan hieroglyphs, and the Phaistos script but none of these has been deciphered by modern scholars and the nature of what languages may have been used on Bronze Age Crete is unknown. With this comes the problem of trying to reconstruct ideology for these cultures through simply art and material culture. Somewhat less opaque are the Mycenaeans, the Minoans’ younger contemporaries on the Greek mainland. Sometime around 1600 BC, the volcanic island of Thera (Santorini) erupted catastrophically and brought about a decline in the island centers, while Mycenaean power and influence grew. By 1400 BC, the Mycenaean complex would push into Crete itself, bringing with it a new writing system known as Linear B, which has been largely deciphered by modern scholars. While the textual record is not extensive, this is enough to tell us that the Mycenaeans used an early form of Greek, signaling that Indo-European languages had arrived in the Aegean world. Recognizable Greek gods appear, though sometimes in different roles from their later more familiar versions. Later Greeks would claim the Mycenaeans as well as this was the age of mythological heroes and many of the great poleis (city-states) of the Greek world were founded in this period. The Minoans and Mycenaeans, like the Harappans, were engaged in international interaction very early, including in the influence of their fine art, as shown from examples such as the Minoan frescoes at Tell el-Dab’a in Egypt, created locally there by presumably Minoan expats in the reign of pharaohs either Hatshepsut or Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC). By the 1100s BC, the various Mycenaean city-states were dominant in the Aegean world but over the course of that century, the major palace centers fell and many cities were destroyed as part of the general event across the Eastern Mediterranean that archaeologists have termed the Late Bronze Age collapse. The details of this event are still debated but in the Aegean world it was particularly dramatic as writing fell out of use altogether and the Greek Dark Ages began.

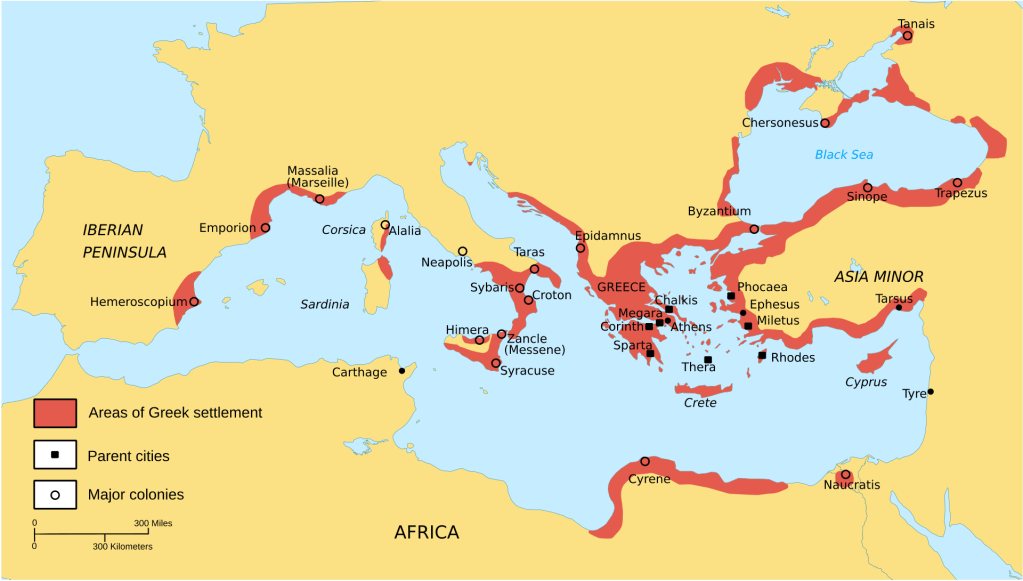

A map of the extent of Greek colonization in the Archaic period between 800 and 500 BC by Wikimedia contributor Dipa1965.

The Greek Dark Ages are called what they are because of an absence of written sources, though in reality archaeology continues to inform us of certain developments in the period. Around the 700s BC, the written word opens again in the region, including ancient Greece’s two most famous poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, which both tell stories set in the Mycenaean period related to characters that participated in the Trojan War, a mythologized conflict between the Greeks and the city of Troy (an actual identified archaeological site) in what is now modern Turkey near the Bosporus. The authors and redactors (traditionally they are attributed to the probably fictionalized Homer), especially in the Iliad, frequently refer to the Greeks collectively as “the long-haired Achaeans,” demonstrating some sort of understanding of a Panhellenic identity, even as the Greeks were divided into many polities in both the stories themselves and the time of Homer. The term “Panhellenes” from which we get “Panhellenic” comes up in only a couple usages in ancient Greek works but today the latter is used to refer to those cultural elements and sites which brought the whole Greek world together, even in its frequently bloody disunity. Among the two most famous Panhellenic sites were the sanctuaries of Zeus at Olympia and of Apollo at Delphi. Olympia played host to the Olympic Games, traditionally founded in 776 BC, which many poleis sent athletes to compete at in honor of Zeus, king of the gods. The Temple of Apollo at Delphi played host to the light god’s oracles, priestesses who would tell, in a trance-like state, prophecies for those who would come to see them. Ultimately the chief political identity of a Greek would be his polis (robust understandings of citizenship existed but this was almost always limited to men) but even from an early time, there was a general understanding of a Greek world that spoke on the same language continuum (Ancient Greek was highly dialectically diverse) and worshiped many of the same gods (which also varied significantly). Throughout this period, the Archaic period in classical-studies terminology stretching from around 800 to 500 BC, Greeks spread out and colonized much of the area around the Mediterranean and Black seas, turning Greek culture into an international prestige culture in the Mediterranean world.

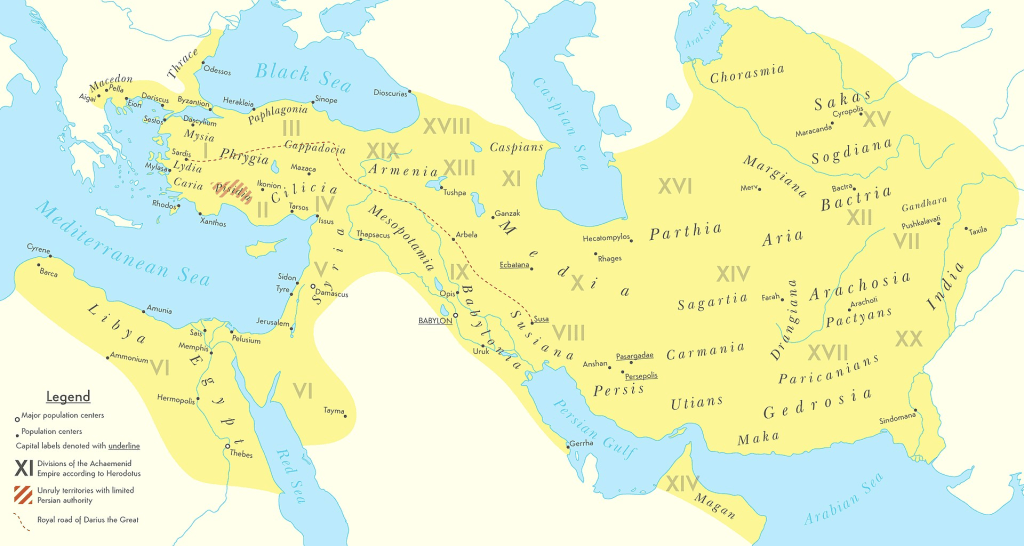

The Achaemenid Persian Empire at its greatest extent under the reign of Darius I the Great (522 to 486 BC) by Wikimedia contributor Cattette.

In the middle of the 500s BC, however, a new empire, the largest the world had yet seen, would conquer to fill the entire space between Greece and India: the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Before the ascent of Persia, the dominant state in what is now Iran was, according to Herodotus, the Empire of the Medes (which is known largely from external sources and somewhat poorly understood, probably existing as a more regional entity than Herodotus portrays it as), while to its southwest the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the last great ancient Mesopotamian state, dominated the entire Fertile Crescent including the Levant. A third great power in the Near East was Lydia, centered in what is now Turkey, which itself had grown in recent centuries to absorb many of the Greek states on the Anatolian coast. The Persians were an Aryan (sometimes called Indo-Iranian to detach from the baggage that term has picked up) people subjected to the Medes who lived on the southern coast of what is now Iran. The Achaemenid Dynasty ruled one of the Persian tribes, the Pasargadae, which in 559 BC, following Herodotus’s timeline, came to be led by Cyrus II, whom history would come to remember as Cyrus the Great. In 552 BC, Cyrus confederated the Persian tribes in a revolution to throw off the Median yoke, marching on the imperial capital of Ecbatana two years later, Medes even joining him if sources are to be believed in throwing off their unpopular ruler Astyages. 550 BC marks the beginning of the first Persian Empire. Cyrus was not done, however, and he invaded and conquered Lydia in 546 BC and Babylon in 539 BC, sculpting an empire that surpassed anything previously by a vast magnitude. After Cyrus’s death in 530 BC in battle against the Scythian tribe of the Massagetae in Central Asia, his successor Cambyses II took Egypt in 525 BC, which for our protagonists the Greeks further solidified the presence of a lone Persian superpower looming over the Eastern Mediterranean.

Starting in 499 BC, Greek communities under Persian rule in an area of Asia Minor (Anatolia) known as Ionia rose up against their rulers. Athens, one of the major city-states in mainland Greece and an emerging democracy, saw an opportunity to knock down Persian hegemony in the region while also spreading its own influence and government system, so it supported the rebellion, which dragged out until the Persians defeated its last holdouts on the island of Miletus in 493 BC. The King of Kings of Persia at the time was Darius I, who ruled from 522 to 486 BC and is remembered as Darius the Great for his significant reforms to the structure of the empire. Darius was angry at Athens for this and decided to invade Greece, which occurred in 490 BC with a landing party of Persian forces landing on the plain of Marathon, only to be met by Athenian resistance that pushed the troops back to the sea. Persia’s second invasion would not be so short. Marching across the Hellespont on a pontoon bridge and walking down through Greece in anticipation of being reinforced by a powerful navy, Persian forces made the Greeks face them on two fronts in 480 BC, now under the reign of Xerxes I. At Thermopylae, the famous last stand of 300 Spartans and their several thousand allies ended with the Persians pushing forward towards Athens while at sea the Athenian destruction of the Persian fleet at Salamis meant the Persian forces would not be reinforced. The next year at Plataea, a combined force of multiple powerful Greek city-states, including Athens and Sparta, finally defeated the Persian invaders and effectively ended the wars.

This bust of Herodotus from the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a Roman copy from the 100s AD emulating a Greek original from the 300s BC.

In the story of the development of a Greek cultural identity, the Greco-Persian Wars loom extremely large. The Greek world, never having been politically unified before, had to practice intensive coalition warfare against an overwhelmingly more powerful threat, something that Greek historians would narrativize as they defined what Greek culture meant. Herodotus was by far the biggest historiographical influence on this process, himself a fascinating case in the fluidity of culture. Living from around 484 to 425 BC, he hailed from Halicarnassus, a Greek city in Persian-controlled Asia Minor, and toured the Greek and Persian worlds, collecting stories which would become part of his Histories, completed sometime around 430 BC. The focus of the work, which became the formative text for the genre of history in the classical Mediterranean, is on the Greco-Persian Wars, which Herodotus portrays as a conflict between freedom and subjugation. The idea of freedom here varies in manifestation between the different groups of the Greek world. For instance, it may mean to a democratic Athenian the right to participate in civic matters while in a less democratic state like Sparta, it may not. After all, like the mahajanapadas of India, the Greek poleis were incredibly diverse in systems of government. Whatever the case, all while highlighting the differences between different poleis, Herodotus generally implies that there are underlying characteristics of Greek culture such as relative egalitarianism (as opposed to Persian authoritarianism) and rationalism (as opposed to eastern superstitions). If you just raised your eyebrow with knowledge of the extensive Greek practice of slavery or participation in a polytheistic religion that wasn’t too unlike those of the ancient Near East, you can’t be blamed. As is the case with national storytelling, tones can be self-congratulatory and be harder on stereotyped exoticisms than society at home. Amidst all of this, we see emerging, despite political disunity, an understood Greek international culture, which would in the coming centuries grow to be world-defining.

The century and a half between the Greco-Persian Wars and Alexander the Great was a time of great change in the Greek world. Confusingly, scholars of ancient Greece refer to this as the “Classical Period” of Greece, which is much more limited in temporal scope than the classical period as used more broadly. Following the Greco-Persian Wars, Athens emerged as the most significant hegemon of the Aegean, creating a defensive alliance called the Delian League in 478 BC in case of future Persian aggression. It became quickly clear though that this league was in practice more a tool of Athenian imperial dominion over other poleis, the city sometimes even attacking its “allies” that failed to pay the defense budget, which Athens spent how it wished. The Athenian dialect, Attic Greek, became widespread in the Mediterranean and as a language of educated learning, which flourished in the city itself. Athenian coins, drachmae, circulated as an emerging international currency throughout the Mediterranean world, even outside Athenian political influence, such as in the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The second most prominent Greek hegemon though was Sparta, which formed its own Peloponnesian League in response to the rise of Athens. The Greek world became split between these two centers of power which became violent in the Peloponnesian War of 431 to 404 BC. After decades of fighting, Sparta triumphed over Athens, installing tyrants in place of its democracy, before itself being beaten by a counter-coalition led by the polis of Thebes. The result of this was an effective power vacuum in the Greek world, waiting to be filled by a new upstart power, which would come in the form of Macedon.

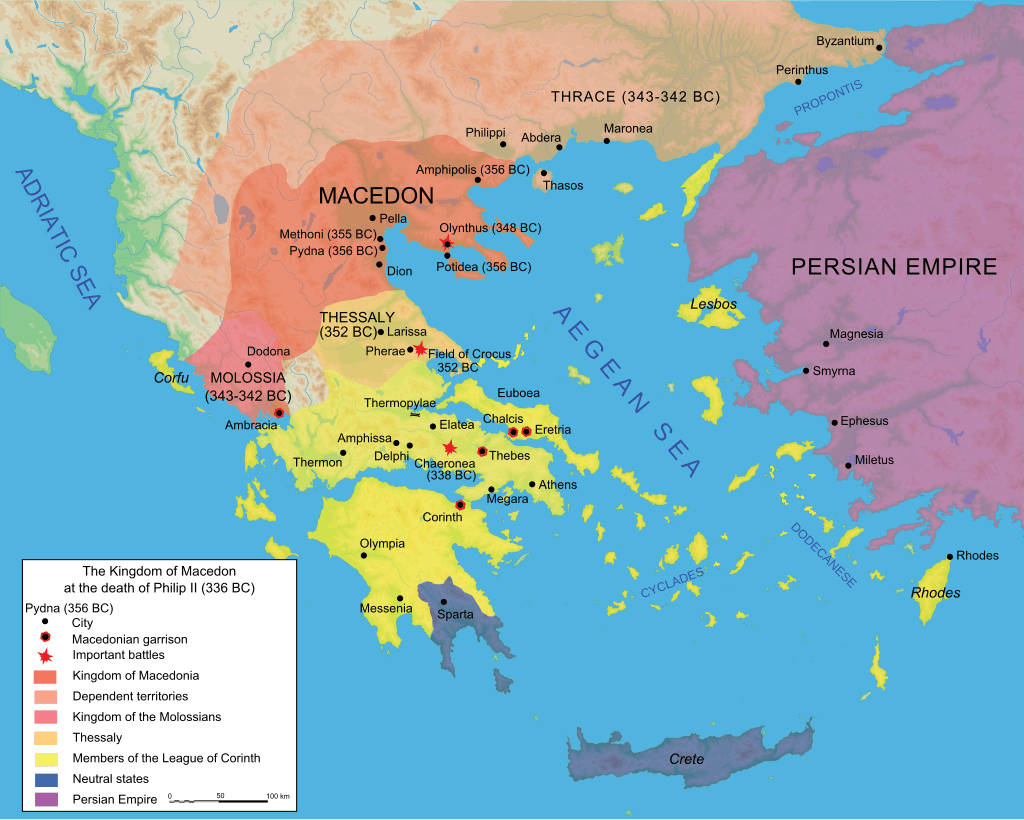

A map of Macedon and its hegemony in 336 BC at the transition between the reigns of Philip II and Alexander the Great. Aside from the kingdom’s external dominance over Thrace, the League of Corinth was also under Philip’s hegemony. Map by Wikimedia contributor Marsyas.

Macedon was a kingdom centered in what is today the very north of Greece and in ancient times it sort of occupied the bounds of what it meant to be Greek. The native dialect was Macedonian, a barely attested language closely related to Greek within the Hellenic branch of the Indo-European tree, but over the course of the century before the Peloponnesian War, the prestige language of Attic Greek had increasingly taken hold there. From 359 to 336 BC, Macedon was under the rule of Philip II who sought to reform the state and play more heavily in the politics of Greece. The central focus of these reforms was the army, which Philip structured around an updated version of the Greek hoplite (a type of foot soldier who fought in a dense formation called a phalanx). Hoplites were replaced with phalangites carrying sarissas, 6-meter-long spears, which would bristle forward to create a wall of death for anyone in the path of the phalanx. To either flank of the phalanx would ride hetairoi or companion cavalry, which would not only cover for the phalanx’s major weakness of being hard to turn but also act as flanking attackers against enemy armies. The secondary focus of reforms was in establishing a patronage system through which elites and soldiers would be granted boons for serving the king, centralizing authority and ensuring loyalty. In a series of campaigns, Philip subjugated Thrace (east of Macedon towards the Bosporus) and invaded Greece, taking cities including Athens which he pushed into a league known as the League of Corinth, effectively an extension of his kingdom’s power. By 336 BC, he was master of most of the peninsula and had begun plans to invade Persian Asia Minor but then in a theater was suddenly assassinated by one of his own bodyguards for reasons that the historical record leaves up to debate. Succeeding him was his young son Alexander III.

Roman mosaic depiction of Alexander the Great from Pompeii.

Alexander the Great, who was born in 356 BC and ruled Macedon from 336 to 323 BC, is a competitor for the role of the most impactful political leader in the history of the world. In his short life, he would remake the world, pushing the bounds of what was known to Greeks before, driving cultural collisions that would overturn the geopolitical and cultural arena of Eurasia, and bringing down the most powerful state that had ever existed up to that point, the Achaemenid Persian Empire. In naming the greatest conqueror that ever lived, some might go for Julius Caesar, Genghis Khan, or Napoleon Bonaparte, all on respectable differences in preference. But unlike Alexander, all of these other men lost battles along the way.

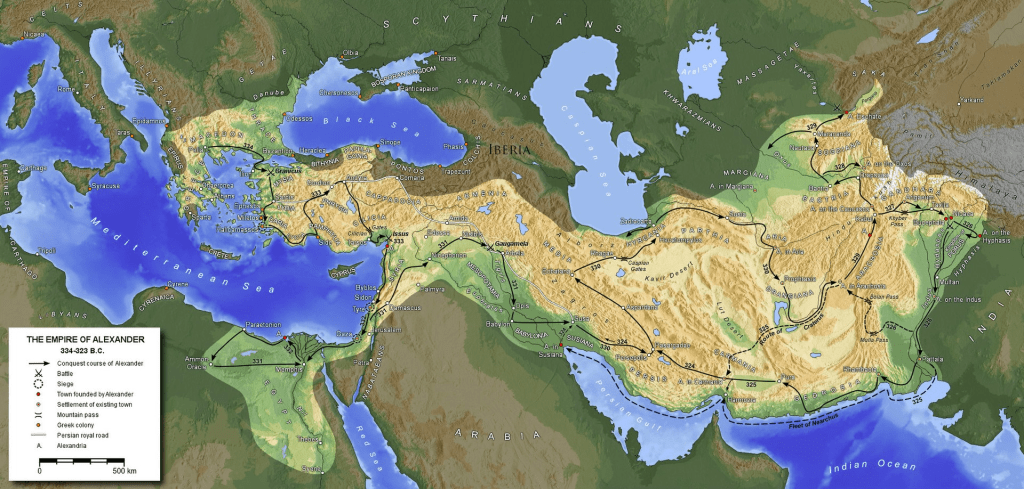

A map of the route of Alexander the Great’s conquest path, complete with the years he moved along each segment of it from Wikimedia.

Alexander began his reign furiously taking care of business. A purge of the court ensued in vengeance for the death of his father and the king was met with subjects in Greece and the Balkans preparing to rise up and break out of Macedonian hegemony in Philip’s absence. He asserted dominance over the League of Corinth and took care of rebellions promptly, soon indisputably the ruler of Greece, and he quelled resistance in Thrace by the end of 335 BC. The next year, Alexander wasted no time in carrying out his father’s ambitions, crossing the Hellespont into Asia Minor and thus commencing an invasion of the Persian Empire itself, where the local Greeks met him as a liberator. Darius III, who had recently come to power also in 336 BC, was slow to respond to Alexander’s entry, probably due to imperial instability resulting from rebellious satraps (the governors of Persian imperial provinces, called satrapies), and may have seen the Macedonian incursion as a small problem that could be dealt with later. He first battled Persian forces at the Battle of the Granicus near the Hellespont in modern northwestern Turkey in 334 BC where the field army of the local satraps was crushed, opening the way for Alexander to take control of the Anatolian countryside. In the southeast of modern Turkey, he finally met Darius III himself at the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, scoring a decisive victory in which the main Persian force was slaughtered along with most of its commanders while the king of kings was forced to flee, opening up the path for a sweep into new lands never before ruled by Greeks.

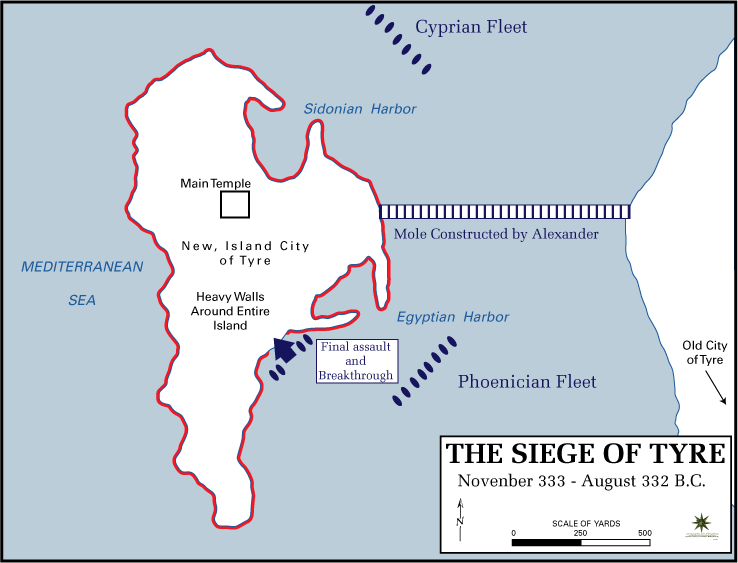

A map of the Siege of Tyre by Frank Martini of the United States Military Academy Department of History.

Alexander continued southward into Phoenicia in the northern Levant. The city of Tyre in modern Lebanon resisted, using its position as an island city off the coast to try to hold out against the Macedonian king’s land-based army for most of 332 BC, but after a long and dramatic siege, Alexander’s solution of constructing a large causeway by which his army could march out to the island paid off. A brutal example was made in the destruction of Tyre and other cities throughout the Persian-held Levant would capitulate easily afterwards. To this day, Alexander’s victory is preserved in the shape of the landscape where sediment has accumulated around where the causeway was so that Tyre is at the end of an oddly shaped peninsula rather than being an island. Conquering southward further through the Levant, Alexander came to Egypt by the end of that year, which had multiple times over the last two centuries rebelled against Persian rule. Presenting as a liberator from the Persians, Alexander took on the title of pharaoh of Egypt and declared himself the son of the ram-headed sun god Amun, whom the Greeks associated with Zeus. (It was fairly common in ancient Greece to interpret foreign deities as expressions of the Olympian ones.) The city of Alexandria on the Nile Delta, one of many cities he would build and name after himself, would become the most important urban center in the region for centuries to come. Increasingly, Alexander presented as not just a Greek ruler but also as a universal monarch who practiced the local traditions of those he now ruled, all while bringing in colonies of ambitious Greeks to new lands who gridded cities and built theaters and colonnaded temples in the Hellenic style. A new age of cultural fusion was beginning.

When the Macedonian pharaoh emerged from Egypt in 331 BC, the Achaemenid Persian Empire remained at large, now in a contracted state, but Alexander would not do with just half. He would be king of kings. He continued towards Mesopotamia, modern Iraq, closer to the heart of Persian territory, where four millennia before the world’s first truly great cities had been built. Expecting that Darius anticipated that he would move on Babylon, the great metropolitan jewel of the region, Alexander instead went about seeking the Persian force across the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. His scouts found it in the north in modern Iraqi Kurdistan where the two kings met on the field yet again for the Battle of Gaugamela. The battle was one-sided yet again and the Persian force collapsed, Darius being forced to flee back towards Iran, what remains of his army were left dispersing back into the lands of the rapidly disintegrating empire. Babylon, Susa, and other cities throughout the region surrendered without resistance. At the Battle of the Persian Gate in 330 BC in the Zagros Mountains of what is now western Iran, it was the Persians’ turn to make a heroic last stand against Greek invaders, but it did not stop the tide and soon the Macedonians came to the Persian capital of Persepolis, which was thoroughly looted and destroyed. Poor Darius fled and Alexander pursued him, only to find his body along the way after he was murdered by Bessus, an ambitious satrap of Bactria (roughly modern Afghanistan) trying to take advantage of the chaos who promptly declared himself king of kings, though Alexander would make quick work of him, arranging a funeral for Darius to honor his old foe. Alexander carried out a campaign through Bactria where he swept up much of the peripheral old Persian territory and made battle with some Scythians on the borders. The Macedonian king took on the title of king of kings and married one of Darius’s daughters. The Near East was now a place of Greek rule. But the Greek conception of the world map had already been stretched by this adventure and it was clear that the world extended even further and there was more for the taking. Diplomacy began with states across the Indus River and Alexander’s armies began to march, catching our Greek narrative of history up with our Indian one. From here, 327 BC, and onwards, we can treat these as part of one world system.

An Arena of Empires and Ideas

Commemorative Macedonian coin from around 322 BC depicting Alexander the Great defeating King Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes, shared to Wikimedia by user PHGCOM.

When Alexander the Great arrived in India, the Nanda Dynasty of Magadha reigned over the eastern and central portions of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, its ascendancy recent, and the connections it drove would allow for the spread of philosophies from near its heartland–Buddhism and Jainism–across North India. It was the small remaining independent states to its west that Alexander encountered. Notable among these was Taxila, a city near modern Islamabad, Pakistan ruled over by a man named Ambhi (though Greek historians such as Arrian often called him Taxiles, seemingly deriving it confusedly from the name of his city). Ambhi was in conflict with two other Indian polities at the time and saw loyalty to the new powerful foreign king as a way to secure his state. A Macedonian garrison was stationed in the region, sparking conflict with Porus, king of the Paurava tribe, Taxila’s most prominent enemy. The Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC was the last truly great battle of Alexander’s career, fought on the marshland across the intensely flowing Hydaspes (modern Jhelum) River in what is now the Punjab region of Pakistan. Alexander and his local allies forded the river to battle the forces of Porus, which came complete with war elephants, something that terrified Alexander’s forces. (War elephants were at this point completely unknown in the Mediterranean world and this conquest was how the concept got there; Hannibal’s famous crossing of the Alps was in 218 BC, barely over a century later.) Nevertheless, the battle went in Alexander’s favor, solidifying his control of the Punjab, though increasingly his troops were exhausted, as some of them had traveled across the world for 12 entire years. Hearing rumors of an even grander army of elephants further east and with supply lines stretched thinner and thinner, Alexander’s troops mutinied en masse, refusing to go further. It was not military defeat that spelled the end of one of history’s most impressive spells of conquest but rather the weight of extreme success.

It was also during this time that the intellectual traditions of Greece and India first encountered one another. Alexander, a pupil of Aristotle, seems to have taken interest in the local philosophers, and indeed Greek records do refer to them as philosophers, acknowledging value in their tradition and wisdom, though sorting out the individual schools of thought be they Brahmanical, Buddhist, Jain, or otherwise is not always possible from the Greek texts that do not distinguish them much, though as I mentioned before these also existed within a diverse cultural continuum without necessarily the strict demarcations they have today, so perhaps this is not very important. Alexander is one of the best-recorded figures of classical antiquity, as he was recorded by figures such as Callisthenes who traveled with him (though unfortunately his work is lost) and these sources were compiled and commented on by Greek, Roman, and Persian historians in the next few centuries. The Anabasis of Alexander by Arrian of Nicomedia, written in Greek under the Roman Empire probably during the reign of the emperor Hadrian (117 to 138 AD), is one of the premier sources for learning about the conquest. I particularly like this episode in the first chapter of his seventh book, where Alexander is contemplating what to conquer next before having an encounter with a group of Indian philosophers, translated here by E. J. Chinnock.

When Alexander arrived at Pasargadae and Persepolis, he was seized with an ardent desire to sail down the Euphrates and Tigres to the Persian Sea, and to see the mouths of those rivers as he had already seen those of the Indus as well as the sea into which it flows. Some authors also have stated that he was meditating a voyage round the larger portion of Arabia, the country of the Ethiopians, Libya (i.e. Africa), and Numidia beyond Mount Atlas to Gadeira (i.e. Cadiz), inward into our sea (i.e. the Mediterranean); thinking that after he had subdued both Libya and Carchedon (i.e. Carthage). he might with justice be called king of all Asia. For he said that the kings of the Persians and Medes called themselves Great Kings without any right, since they did not rule the larger part of Asia. Some say he was meditating a voyage thence into the Euxine Sea, to Scythia and the Lake Maeotis (i.e. the Sea of Azov); while others assert that he intended to go to Sicily and the Iapygian Cape, for the fame of the Romans spreading far and wide was now exciting his jealousy. For my own part I cannot conjecture with any certainty what were his plans; and I do not care to guess. But this I think I can confidently affirm, that he meditated nothing small or mean; and that he would never have remained satisfied with any of the acquisitions he had made, even if he had added Europe to Asia, or the islands of the Britons to Europe; but would still have gone on seeking for unknown lands beyond those mentioned. I verily believe that if he had found no one else to strive with, he would have striven with himself. And on this account I commend some of the Indian philosophers, who are said to have been caught by Alexander as they were walking in the open meadow where they were accustomed to spend their time. At the sight of him and his army they did nothing else but stamp with their feet on the earth, upon which they were stepping. When he asked them by means of interpreters what was the meaning of their action, they replied as follows: “O king Alexander, every man possesses as much of the earth as this upon which we have stepped; but thou being only a man like the rest of us, except in being meddlesome and arrogant, art come over so great a part of the earth from thy own land, giving trouble both to thyself and others. And yet thou also wilt soon die, and possess only as much of the earth as is sufficient for thy body to be buried in.”

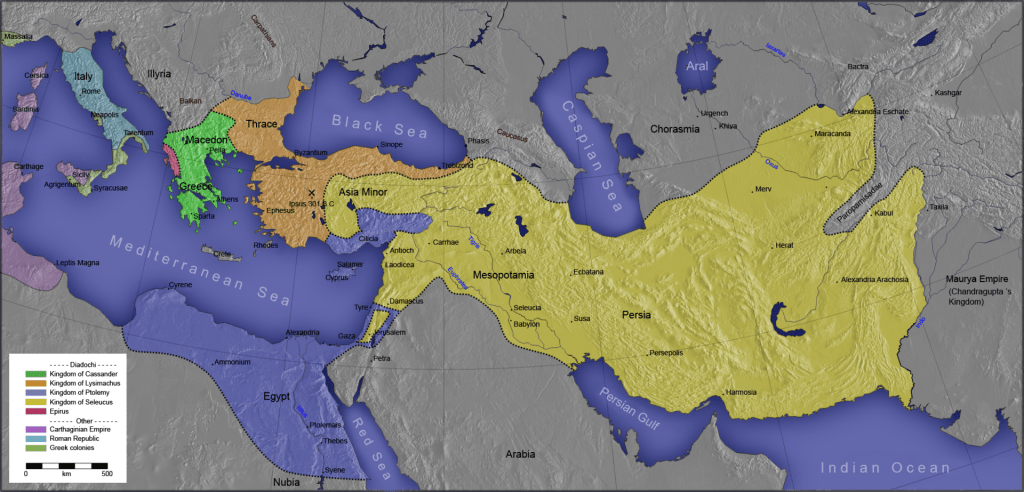

Alexander’s vanity was on full display when he marched his army back on a torturous return through the deserts of Iran, possibly intentionally punishing his troops for robbing him of further glories. Alexander’s health however was not particularly great in this time and the difficulty of the passage may have had further ill effects on it. In Persia, he would go about the business of arranging marriages between himself and his elites with the Persian elites to further solidify control, especially as his empire was somewhat unsolidified, thanks to his habit of briefly passing through places to conquer whatever he could get to next. In 323 BC, having returned west to Babylon, Alexander suddenly had a fever, possibly from malaria which is endemic in the swamps of southern Mesopotamia and possibly from something else, and he soon succumbed and died, just shy of turning 33 years old. He had constructed a new world in which Greco-Macedonian administrators were placed in control of the entire Near East from Egypt to Bactria. They had constructed new cities and melded the Greek way of doing things with local traditions, creating what historians have come to label as a period of Hellenization, the Hellenistic period (generally 323 to 30 BC). But the more immediate concerns on June 11, 323 BC were political, because in the hereditary monarchy at hand Alexander, up to that point ruler over the largest portion of the world ever commanded by a human being, had no heir. A regent was put in place by the name of Perdiccas (who would wind up murdered by his officers three years later) and one of Alexander’s several queens Roxane of Bactria was pregnant with a child, who would be born as Alexander IV and nominally reign from 322 to 309 BC before being the subject of child regicide because he was an inconvenience to the powers that be. The powers that be were Alexander’s generals, specifically Cassander, Lysimachus, Ptolemy, and Seleucus. The most powerful empire on Earth was about to implode and fragment just as it had been born.

The kingdoms of the Diadochi or successors of Alexander the Great as they were in 301 BC, as well as some other Mediterranean powers, by Wikimedia contributor Luigi Chiesa. Light green is Macedon under Cassander, orange is the short-lived Kingdom of Lysimachus, dark blue is Ptolemaic Egypt, yellow is the Seleucid Empire, and red is the small Kingdom of Epirus, which under its king Pyrrhus would engage in a brief period of expansion in Italy. The purple and light blue represent the domains of the Carthaginian and Roman republics respectively, which were approaching the start of the Punic Wars in vying for power in the Western Mediterranean, while the dark green represents the many independent Greek colonies that still existed out west, despite Macedonian dominance in Greece.

The powerful generals established their own spheres of influence and controlled parts of the empire, increasingly fighting with one another. The Wars of the Diadochi (successors) of 322 to 281 BC are too long and complex to devote much space to here but for the sake of establishing some of the geographical arena, we should go over them. Lysimachus carved out a kingdom in Asia Minor and Thrace which he ruled from 306 to 281 BC before dying in battle and having it lapped up by the kingdoms of Cassander and Seleucus. Cassander was not himself one of the generals of Alexander but rather the son of his general Antipater. He oversaw things in Macedon and Greece until after the death of little Alexander IV when he took the throne of Macedon himself in 305 BC, reigning until 297 BC and solidifying Macedonian rule over the Greek heartland even in this chaos, which would last until the Romans conquered the region in the mid-100s BC. Seleucus Nicator I (ruled 305 to 281 BC) took hold of the most significant chunk of the empire, what became known as the Seleucid Empire, which stretched from Syria and Anatolia all the way to Bactria and the Indus, encompassing the old lands of Babylon and Persia along the way. This gigantic unwieldy empire would spend most of the next two centuries losing territory in a long protracted decline and will feature again significantly in our story of Greco-Indian interaction. The most successful post-Alexandrian dynasty would be the truly Alexandrian one, ruling out of the conqueror’s so-named city on the Nile Delta (and possessing Alexander’s body, which they specifically stole away from plans to bury in Macedon). Ptolemy I Soter, who ruled Egypt from 305 to 282 BC, declared himself pharaoh and took on the traditional roles of Egyptian rulership, starting a dynasty that would last for the next three centuries, establishing the Great Library of Alexandria and ending with Cleopatra VII (yes, that one) in 30 BC.

This photo from the Archaeological Survey of India of 1926-1927 displays the unearthed wooden palisade wall of ancient Pataliputra, which was the capital of the Maurya Empire. These fortifications were witnessed firsthand and recorded by the Greek (or Hellenized local) ambassador Megasthenes, who operated in the city during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya.

As the Macedonian Empire fractured, another empire to the east was being born. Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire and one of the most famous rulers in Indian history, is simultaneously a figure on which many narratives have been written and a figure about which little is concretely known. So to tell his story in a way that fits the informational standards I try to apply here, I have to tell you about the sources we have for this dramatic transitional phase of Indian history. Broadly, we can divide the historical tradition on Chandragupta into Greek and Indian sources, which actually cross over little in what they record beyond placing Chandragupta (“Sandrocottus” to the Greeks) as the founder of an empire and dynasty and leading armies. Greek sources represent the earliest extant accounts of him. Sources such as Arrian have Seleucus meet in battle with Chandragupta in the Indus Valley sometime between 305 and 303 BC (it is unclear from these sources if Chandragupta had already become ruler of Magadha at this point, though most popular narratives imagine so; the usual chronology of the establishment of the Maurya state is largely rooted in tradition rather than objective information) and the outcome of the battle is unclear but it seems to have ended in a treaty and an intensification of diplomatic relations between the two kings that would continue throughout the coming history of their empires. It is via the Romanized Greek writer Plutarch (who lived from around 46 to 119 AD) that we get the famous story of Chandragupta gifting 500 elephants to Seleucus in exchange for land cessions. The most important Greek source on the early Maurya Empire though is Megasthenes, a writer and diplomat in the service of Seleucus who traveled to the Maurya court (presumably in Pataliputra, modern Patna) and recorded extensively on India in his four-part work Indica which is lost to us but heavily referenced and commented on by later Greco-Roman writers to the extent that we have a general idea as to its contents. Megasthenes recorded fortifications that have also been identified by archaeologists in the area around Patna, helping to date them to the reign of Chandragupta or slightly earlier in the Nanda period.

This sanctuary around a cave in Chandragiri in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh dedicates the site where according to Digambara Jain tradition, Chandragupta Maurya and Bhadrabahu died through ritual starvation or sallekhana. Scholars do not believe this event actually happened. This image is by Wikimedia contributor Amol.thikane.

Indian sources on Chandragupta are largely related to the relationship of the Maurya Empire to early Buddhist and Jain history, are hagiographical in nature, and are often very late. However, unlike the Greek sources, they do provide more of a life story. The most influential of these has been the Parishishtaparvan, an epic poem about the early figures of Jainism written in the 1100s AD by the medieval Jain philosopher Hemachandra. This text associates Chandragupta with a wise Jain teacher named Chanakya (who is a chief minister to Chandragupta in many stories; it is also to him that the famous ancient Sanskrit political treatise the Arthashastra is traditionally credited, though it was probably actually written by multiple authors over several centuries during and after the Maurya period) who recognizes the boy’s talent and intelligence from an early age and decides to try to make him king. The two manage to hire mercenary troops and establish a political presence on the western periphery of the Nanda Empire. Chandragupta attempts to attack the imperial capital to overthrow the king and meets failure before then switching up his strategy by first conquering various peripheries and then successfully taking the capital. Regardless of the historicity of this campaign progression, the intention of the text is religious and moral and therefore it can be seen as teaching a lesson about doing tasks that help one get to a final goal before charging directly at that final goal (Hemachandra wrote for the purpose of explaining aspects of the Jain faith to his patron King Kumarapala of the Chaulukya Dynasty of Gujarat who ruled from 1143 to 1172 AD and was a convert to Jainism). Having ascended to rule an empire, he ruled justly and adopted Chanakya’s faith. The idea that Chandragupta went through this religious transition is actually written on at length in Jain tradition. In the Digambara Jain tradition (only in sources more than a thousand years after the time of Chandragupta), it is said that the monk Bhadrabahu predicted an impending famine that would plague the Maurya Empire in karmic justice for the sins of violence that the king had to participate in to build his empire and so a reformed Chandragupta abdicated the throne and carried out the extreme atoning discipline of sallekhana, ritual death by voluntary starvation. Chandragupta’s supposed conversion is an innovation of the medieval period and not found in non-Jain sources so while it constitutes one of the most famous aspects of his legacy, it is not considered historical by scholars, but it does say something about how great Chandragupta was perceived as that he would be claimed by a major Indian faith that he was around for the early history of. Much earlier Buddhist texts refer to the king such as the Milindapanha (which details the conversion of Greco-Bactrian king Menander I to Buddhism; more on him later), which was written between 100 BC and 200 AD mention the great dynastic founder and he often features in chronologies counting the years between the life of the Buddha and the conversion of Chandragupta’s grandson Ashoka (whom the primary source I opened this article with comes from). It’s these chronologies that the often-stated dates of 322 to 297 BC, give or take a few years, come for his reign.

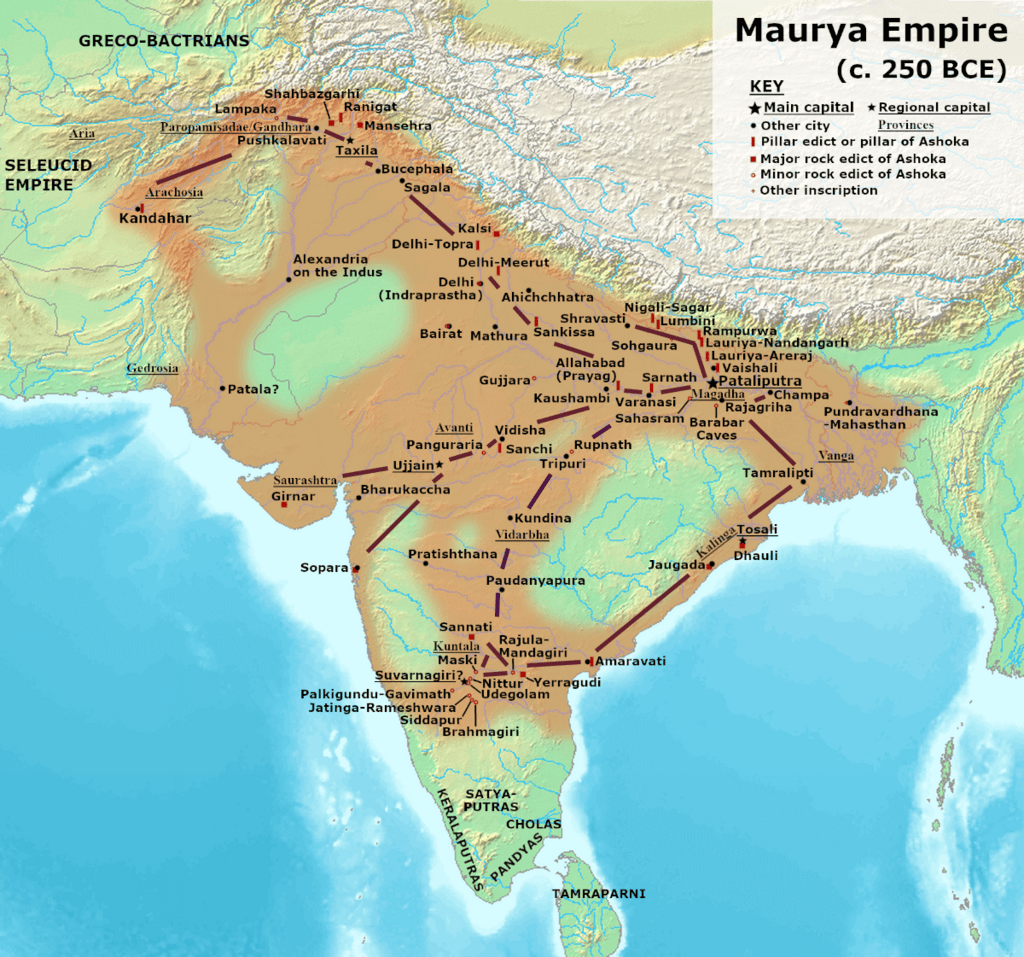

A map of the Maurya Empire at the height of its power under the reign of Ashoka Maurya around 250 BC, conceptualized as a system of settlement connections between different power centers. This image includes the conquests that happened after the reign of Chandragupta such as the Kalinga War. Because the empire operated under a system of vassalage in which multiple layers of authority determined the extent of political power, we can imagine a map of the empire being something like a network of points with porous areas in between. This map is by Wikimedia contributor Joshua Jonathan.

Whatever the exact details of his life, after 300 BC the entirety of North India was under the hegemony of a single state for the first time: the Maurya Dynasty of Magadha, which centered on Pataliputra and oversaw what has come to be remembered as something of a golden age in the history of the subcontinent. The traditional reign of Chandragupta is placed at 322 to 297 BC (keep in mind that this may not be accurate) and after him tradition places the reign of his son Bindusara at 297 to 273 BC. If little is known about Chandragupta, even less is known about Bindusara. The reign of Bindusara’s son Ashoka then, traditionally placed as ruling from 268 to 232 BC, represents a dramatic turnaround due to the explosion of inscriptions as well as literary output. It is during his reign that the oldest extant examples of physical texts we have in the Indian Subcontinent (excluding the far older and by this time long forgotten Indus Valley script) come from. (This doesn’t mean writing was not happening in the centuries before this, but it does mean that Indian states in the Vedic period were not raising the same sorts of monumental inscriptions and probably that much writing was on perishable materials that did not preserve well in the humid climate.) Ashoka, like Alexander, is one of those rulers who forever impacted a vast chunk of the world. He is likely the second single most important figure in our story.

Rock depiction of Ashoka Maurya in his chariot from the Buddhist stupa at Sanchi carved in the first century of either BC or AD. Photo by Anandajoti Bhikkhu.

If you’re familiar with Ashoka Maurya, it’s likely in the context of his conversion to Buddhism. We know of his conversion from later sources but also crucially from the man himself. In the rock inscription I opened this article with (and in many others of his inscriptions), Ashoka credited his conversion to remorse following the violent conquest of Kalinga (completed in 261 BC), a smaller kingdom located primarily in what is now the Indian state of Odisha. Seeing the incredible amount of violence he unleashed, the king was overcome with guilt and sought to devote himself to ahimsa or nonviolence, converting to the Buddhist Dharma. Or so he narrates. It is important to remember the propagandistic aspect of these inscriptions and that they communicate not a pragmatic relationship of ideology and policy but rather the relationship of ideology and policy that the Maurya state would have wanted its subjects to understand, combined of course with the way the powerful monarch at the top saw himself to an extent. Either sensitively or damningly depending on how you judge Ashoka’s sincerity, the association between the Kalinga War and his conversion is not made on the engravings in the actual Kalinga region (perhaps it was important for the conquered people to remember that a powerful empire was lording over them). Whatever the case, the conversion sent ripples through every aspect of Indian society. Buddhism was promoted and stupas and other temples were constructed. Religious tolerance is preached in the rock inscriptions, though political expediency may have put limits on that at times, as suggested by Ashoka’s oppressive action against the “forest-dwellers” or at least threats and boasts of as much. Some friction with the Brahmanical religious elites can be detected through Ashoka’s presence in later Hindu sources. In the Puranas for instance (composed between the 200s and 900s AD), the Buddha and Mahavira are both sometimes called by the word “mayamoha,” simultaneously labeling them as deceivers and deceived, effectively the spreaders of heresy, signaling that as time went on and Buddhism became more prominent, it became something of a problem to the religious authorities that be. The Mahabharata (compiled between the 200s BC and 300s AD) includes a brief remark about a king called Ashoka who is created in the same manner that many of the villains hostile to the heroes of the epic were. Ashoka has been greatly reclaimed by Indian history as a wise and mighty king, easily the most powerful ancient Indian ruler, prior to the emergence of the early modern Mughal Empire, but it seems sources closer to his place in time were more divided on him, as is often the case with leaders who take their realms in new directions.

A Greek translation of Ashoka’s Rock Edicts 13 and 14, photographed in Kandahar, Afghanistan in 1963 by Schumberger.

Nevertheless, despite this nuance, it’s clear that Ashoka had at least a strong sense of attention to human well-being. His edicts suggest widespread legal reforms such as giving those condemned to death a chance to appeal and there is a strong concept of moral rulership and state morality. Despite religious toleration being a stated policy, the state was not secular in the modern sense however and Ashoka was not neutral in sectarian politics. He refers to himself as “Beloved-of-the-Gods” (very much an appeal to divine-right kingship) and presents himself as a disciple of Buddhism who is shaping his mode of rule in practice of his new religion, attempting to create a society of compassion and devotion to his concepts of righteousness and justice. Part of this is promoting his new ideology. Aside from patronage of stupas in the Maurya realm, Ashoka also sent missionaries abroad to his various neighbors. Within Major Rock Edict XIII he mentions sending missions to the various Greek states (the Greeks are called Yonas in Indian texts, derived from Ionia, the same Greek region of Anatolia that revolted against the Achaemenid Empire to start the Greco-Persian Wars), name-dropping a number of Hellenistic kings who were his contemporaries, giving us some grasp of how far these ventures extended. Included is Antiochus II of the Seleucid Empire, Ptolemy II of Egypt, Antigonus II of Macedon, Magas of Cyrenaica (that is the eastern coastal region of modern Libya, long home to Greek colonies), and Alexander II of Epirus (the western coast of modern Greece and southern Albania). Traditions in the Buddhist world claim connections to Ashoka as well. Sri Lankan chronicles associate the coming of Buddhism to their island with Ashoka’s son Mahinda and the chronology of the religion’s arrival in the region seems about correct. South India and Myanmar appear to have also received Buddhist influences in this time. Among Ashoka’s subjects who came to practice the religion were many in Gandhara, a region that is now today mostly in northern Pakistan. This region is interesting among regions of the Maurya Empire because it retained a significant Indo-Greek population descended from those who had settled in the region in the time of Alexander the Great. As the Maurya Empire had been established and pushed west, they had become one of its many peoples, many even being part of the court and with political influence. After all, their language was the lingua franca and means of connection with the entire known world to the west of the empire. Koine Greek, a form of simplified Attic Greek that became widespread in the Hellenistic world, was simply the most widespread language on Earth in the classical world, used for interactions from the mouth of the Mediterranean to the Ganges Valley.

Besides Ashoka’s own translation of his edicts into Greek, we unfortunately have no Greek texts referring specifically to the missionary activities he propagated, but we do know of extensive Greek references to Indian thinkers and spiritual practitioners. Of particular note were the gymnosophists, “naked teachers,” a blanket term applied to the ascetic wise men of the Indian Subcontinent. As I’ve mentioned before, the Greek commentators generally do not differentiate between different schools of Indian thought so the gymnosophist category is likely describing more than one of them. Considering the propagation of Buddhism into the Hellenistic world, we can assume that often described gymnosophists may be Buddhists, but this is probably not true for all of them. In the Greek world, sophists were teachers of wisdom. A familiar example may be Socrates as he appears in Plato’s dialogues (Socrates was active in the late 400s BC and Plato in the early 300s BC, both in Athens), wandering public spaces as a respected (and reviled) wise man who challenges conventions in order to teach and learn about living life the best way. By placing Indian ascetics in the category of sophists, the Greeks were recognizing them as teachers one might go to for wisdom in a similar way, though not necessarily in the structured teaching sense of like the Platonic Academy. Naked sophistry does indeed have a long history in India. Within Jainism for instance, the Digambara school has a long and continuing tradition of nude asceticism. The nakedness of gymnosophists probably includes both those who were actually fully naked and those who wore light garments like loincloths. These were often wanderers, like the sannyasins of modern India, who practiced renunciation of the things of this world in order to make spiritual progress. Analogous mindsets and practices have long been common in Buddhism, including in the traditional narrative of the life of the Buddha himself. The gymnosophists even impacted philosophy back in Greece itself. Pyrrho of Elis, who traveled with Alexander the Great, is said to have stayed and learned among them before going back to Greece, where he would become an influential philosopher himself, remembered as the father of skepticism.

The approximate territorial extent of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom around 170 BC under the reign of Eucratides the Great in an uncredited map from Wikimedia.

For the first half a century after the division of Alexander’s empire, the mighty Seleucid Empire dominated the Near East, from the Levant to Iran. While only one of several successor states, it had emerged from the Wars of the Diadochi as effectively the largest empire on Earth. As rulers of the old Persian heartlands, the Seleucid Dynasty followed the practical approach of maintaining the Achaemenid systems of maintaining imperial governance, investing a lot of power in regional governors known as satraps, who could administer to their specific regions’ needs. Thus, as the Seleucids Hellenized the Near East with amphitheaters, gymnasiums, language, and art, they ruled like kings of kings of Persia. Unfortunately for them, they were not as good at maintaining this system as the Achaemenid Dynasty had been and it would slowly erode over the next couple centuries. In around 256 BC, while Ashoka was ruling in India, the satrapy of Bactria, centered on modern Afghanistan, successfully broke away from the Seleucid dominion and began its time as an independent kingdom that historians largely call Greco-Bactria. While Afghanistan may not seem like it today in the age of sea travel, the center of Asia has for thousands of years been one of the most desirable places to rule if overland trade is your thing. To the west, Greco-Bactria had access to the interconnected Hellenistic world while to the southeast through the Khyber Pass, it had access to the vast wealth of Maurya India. A third lucrative connection was in the process of forming to the east, as within decades after the formation of Greco-Bactria, the state of Qin would begin to conquer all the other Chinese polities, leading to the ascendancy of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a united China, in 221 BC. Greco-Bactria stumbled into ruling the Silk Road right as the Silk Road was being born. In the 100s BC, the Maurya Empire began to totter, ending sometime around 185 BC as the last of its emperors, Brihadathra, was assassinated by his general Pushyamitra Shunga, who would establish a successor state called the Shunga Kingdom in the Gangetic Plain while the rest of the former Maurya realm Balkanized into rule by local officials. This left a power vacuum in northwest India that the rising Greco-Bactrian kingdom could exploit, as rulers like Demetrius I brought back the Greek foothold on part of the Indian Subcontinent. (Another important development relative to themes of our story is that with the fall of the Maurya Empire, state support for Buddhism in North India dried up. It was, after all, still a minority religion. The Shunga rulers and other Maurya successor states generally supported the Brahmanical caste’s religious authority, which often by this point saw Buddhism as heterodox, with long-lasting effects towards Hinduism’s particular dominance in the region today. Buddhism continued to blossom in many neighboring regions, however, such as South India and Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and the Indo-Greek regions.)

Portrait of Menander I of Greco-Bactria from a coin. Image from the Classical Numismatic Group.

Unfortunately, compared to the more famous Diadochi kingdoms, Greco-Bactria and other Indo-Greek regions are not as well recorded by extant records. This means that our list of rulers and their exact chronologies are incomplete and imprecise. However, the Greek record is compounded by Indian and later even Chinese sources that provide fascinating new perspectives on the period. Much of the chronological reconstruction of the Indo-Greek regions relies on the propagation of coinage. The use of round standardized metal coins began in Iron Age Lydia before being adopted by both the classical Greek city-states and the Achaemenid Persians who conquered the Lydian Kingdom. In the Hellenistic period, Alexander and his successors propagated the model of coin on which a king’s visage and name were stamped, that all commerce might take place in the name of the king, the practice being a powerful propaganda mode of allowing a wide breadth of society to see the king in some way in the days before mass media and emphasize his importance. Because coins tended to be restamped by the state with new rulers when possible, stashes of coins are often useful for dating archaeological materials in relation, but the reverse is also true where radiometric or other dates matched with coin collections can be used to try to date the reigns of the associated kings. One of the most noted kings of Greco-Bactria, both in coin finds and in the scant mentions in Greek records, is Menander I, who is believed to have reigned in the middle of the 100s BC. Strabo, a Greek geographer in the Roman Empire in the first century AD, composed his great work Geographica on the various regions of the known world, and included a brief reference to this king while talking about the Indo-Greeks, which suggests some magnificent achievements. The following is from the translation by Duane W. Roller.

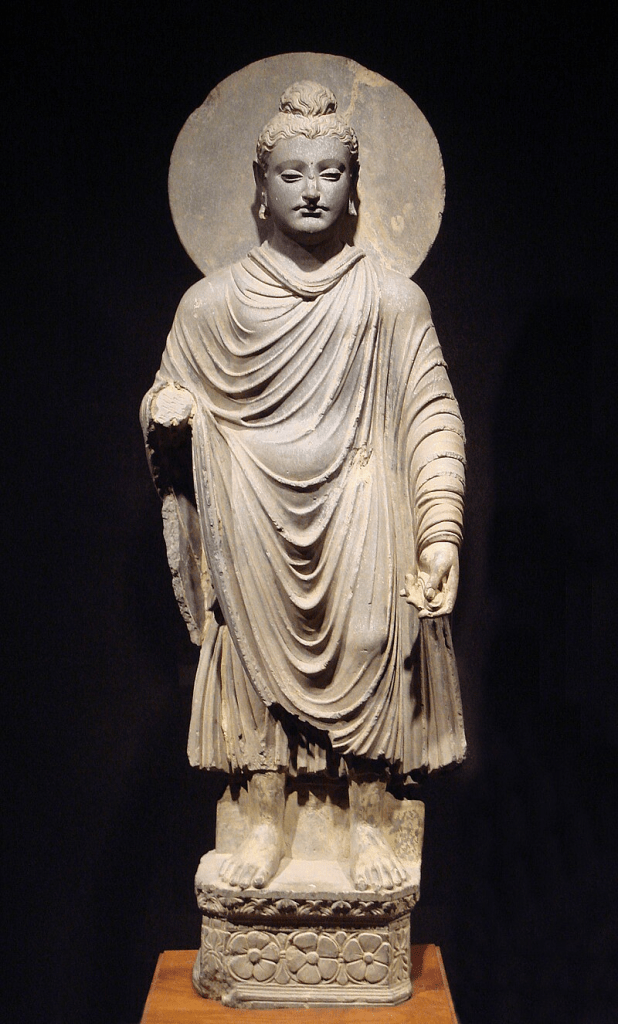

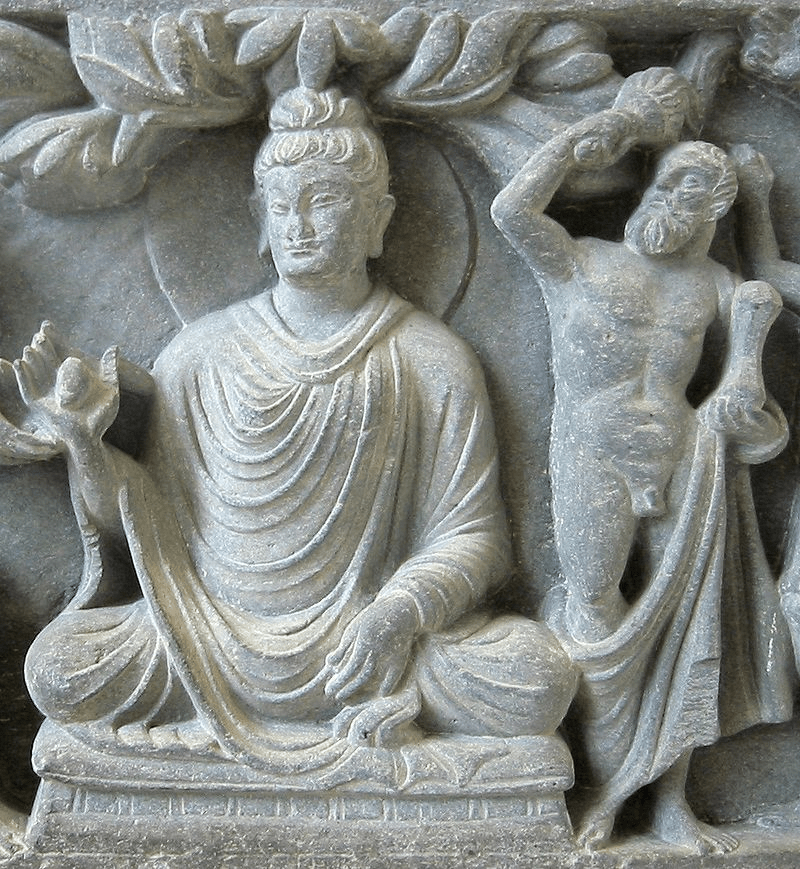

The Hellenes who revolted became so powerful because of the quality of the territory they became the masters of both Ariane and the Indians (as Apollodoros of Artemita says), subduing more peoples than Alexander, especially under Menandros, if he did cross the Hypanisis toward the east and went as far as Isamos. Some he [subdued himself] and others [had been subdued] by Demetrios the son of Euthydemus, king of the Baktrians.