The following is a quotation from the Arab historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari (1301-1349) in his great work on the administrative history of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517). He wrote it in either 1337 or 1338 concerning an event that had occurred in the Mamluk capital of Cairo (where he was living at the time of writing) earlier in 1324-1325 (before he had arrived).

From the beginning of my coming to stay in Egypt I heard talk of the arrival of this sultan Musa on his Pilgrimage and found the Cairenes eager to recount what they had seen of the Africans’ prodigal spending. I asked the emir Abu… and he told me of the opulence, manly virtues, and piety of his sultan. “When I went out to meet him {he said} that is, on behalf of the mighty sultan al-Malik al-Nasir, he did me the extreme honor and treated me with the greatest courtesy. He addressed me, however, only through an interpreter despite his perfect ability to speak in the Arabic tongue. Then he forwarded to the royal treasury many loads of unworked native gold and other valuables. I tried to persuade him to go up to the Citadel to meet the sultan, but he refused persistently saying: “I came for the Pilgrimage and nothing else. I do not wish to mix anything else with my Pilgrimage.” He had begun to use this argument but I realized that the audience was repugnant to him because he would be obliged to kiss the ground and the sultan’s hand. I continued to cajole him and he continued to make excuses but the sultan’s protocol demanded that I should bring him into the royal presence, so I kept on at him till he agreed.

When we came in the sultan’s presence we said to him: “Kiss the ground!” but he refused outright saying: ‘How may this be?’ Then an intelligent man who was with him whispered to him something we could not understand and he said: ‘I make obeisance to God who created me!’ then he prostrated himself and went forward to the sultan. The sultan half-rose to greet him and sat him by his side. They conversed together for a long time, then sultan Musa went out. The sultan sent to him several complete suits of honor for himself, his courtiers, and all those who had come with him, and saddled and bridled horses for himself and his chief courtiers…

This man [Mansa Musa] flooded Cairo with his benefactions. He left no court emir nor holder of a royal office without the gift of a load of gold. The Cairenes made incalculable profits out of him and his suite in buying and selling and giving and taking. They exchanged gold until they depressed its value in Egypt and caused its price to fall.”…

Gold was at a high price in Egypt until they came in that year. The mithqal did not go below 25 dirhams and was generally above, but from that time its value fell and it cheapened in price and has remained cheap till now. The mithqal does not exceed 22 dirhams or less. This has been the state of affairs for about twelve years until this day by reason of the large amount of gold which they brought into Egypt and spent there…

Mali From Outside and In

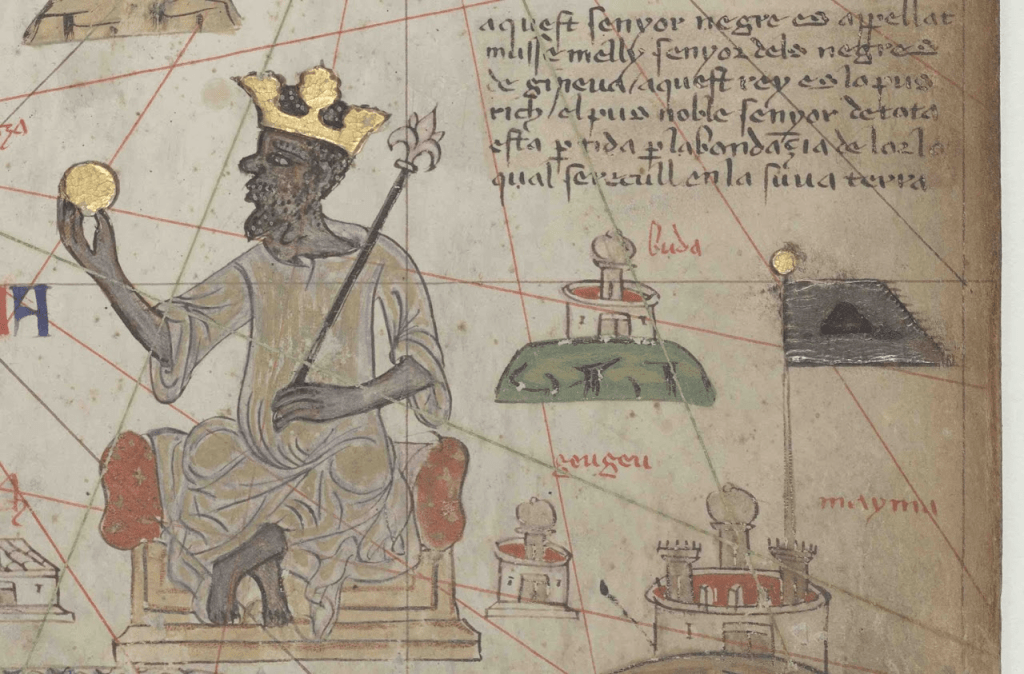

Mansa Musa as depicted on the 1375 Catalan Atlas by Jewish Aragonese cartographer Cresques Abraham. The label says, “This black Lord is called Musse Melly and is the sovereign of the land of the negroes of Gineva [Ghana]. This king is the richest and noblest of all these lands due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands.”

If you’re an avid reader of medieval history, even if you’re not particularly familiar with al-Umari or the other Arab historians, the above scene is probably one you’ve encountered some recounting of. In 1324, Mansa Musa, emperor of the extensive West African polity of Mali, a pious Muslim and the richest person who ever lived, set out on a hajj to Mecca with the most opulent baggage train imaginable, dispensing so much gold that it severely inflated the gold market of the otherwise affluent Mamluk Sultanate. That version by al-Umari is the best primary source on the matter and most narrations of the occasion use the details from it. But it would be unfair to suggest that Musa’s legendary status stems wholly from this one account as his dramatic journey caught eyes across the Mediterranean world. In 1375, Cresques Abraham’s great world map the Catalan Atlas, produced in the Spanish Kingdom of Aragon, shows the great mansa inspecting a gold nugget near the Niger River and, in 1377, Ibn Khaldun’s famous history gives the West African ruler a mention as well, as the wealth of his sub-Saharan empire certainly hung heavy over the great historian’s focal area of Morocco.

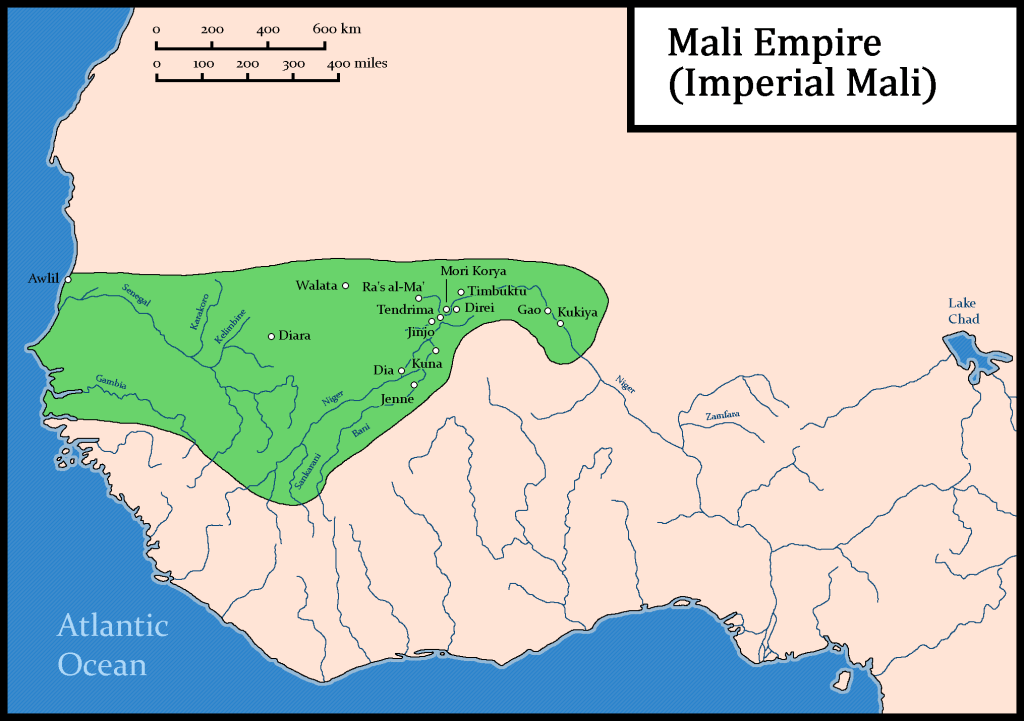

A map of the Mali Empire at its maximum territorial extent from Wikimedia contributor HetmanTheResearcher.

For those unfamiliar, the Mali Empire was a state that existed from about 1235 to 1672, reaching the height of its power in the 1300s. Its core area of urbanism was along the Niger River in West Africa and it extended to the west into the Senegambia region, all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. At its height, it was the largest state in sub-Saharan Africa. The capital of the empire was Niani, a no-longer existent (and not located by modern archaeologists) settlement on the Sankarani River, a tributary of the Niger which starts in the modern country of Guinea and runs into the southwestern part of the modern country of Mali.

Having been at its height merely 700 years ago, the Mali Empire is, unlike some of the other topics on this site, well within the confines of the historical period, described in a number of oral and written sources. The nature of these sources is important to understand. As mentioned above, a lot of these are the sources of the Arab world and to a lesser extent Christian Europe. As an Islamic kingdom for most of its history, Mali was involved in the Classical Arabic literary tradition and part of the Islamic world at large, even if separated from its core by the Sahara Desert. Aside from Moroccan historians such as Ibn Khaldun and Mamluk historians such as al-Umari, the Arab world was home to those who had visited the empire itself, most famously the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta who visited Mali in around 1352. While outside historians were certainly informed by regular Arab visits to the empire, Ibn Battuta’s account is the single significant written eyewitness account we have left today. As a society that participated in Islamic learning, the internal written documents of the Mali Empire were in Classical Arabic but they largely focused on Islam and were restricted to an urban scholarly elite who were Islamic and religiously educated. As such, they rarely give much insight to the indigenous traditions of the empire. Significant oral literature existed in the Malinke language (the language of the ruling ethnic group of the empire) and was preserved by specialized bards called griots who would memorize these sources and the relevant songs and dances that often accompanied them. The tradition of the griots continues to this day and includes legacies of the world of the Mali Empire, including everything from indigenous rituals to the royal histories of the kings or mansas. In general, there is often a general accord between Arab and indigenous sources, with different foci and points of view of course, but sometimes they diverge and when that happens reconstructing histories needs to weigh the problems of both outsider perspectives and oral traditions. There is of course also the ever-present source of archaeology, which does not rely on literary sources and provides different types of information. All of these sources inform the story we will tell today as we dive into what the economy of the Mali Empire was like. But before we can do that, a general history is warranted.

An Empire of the Sahel

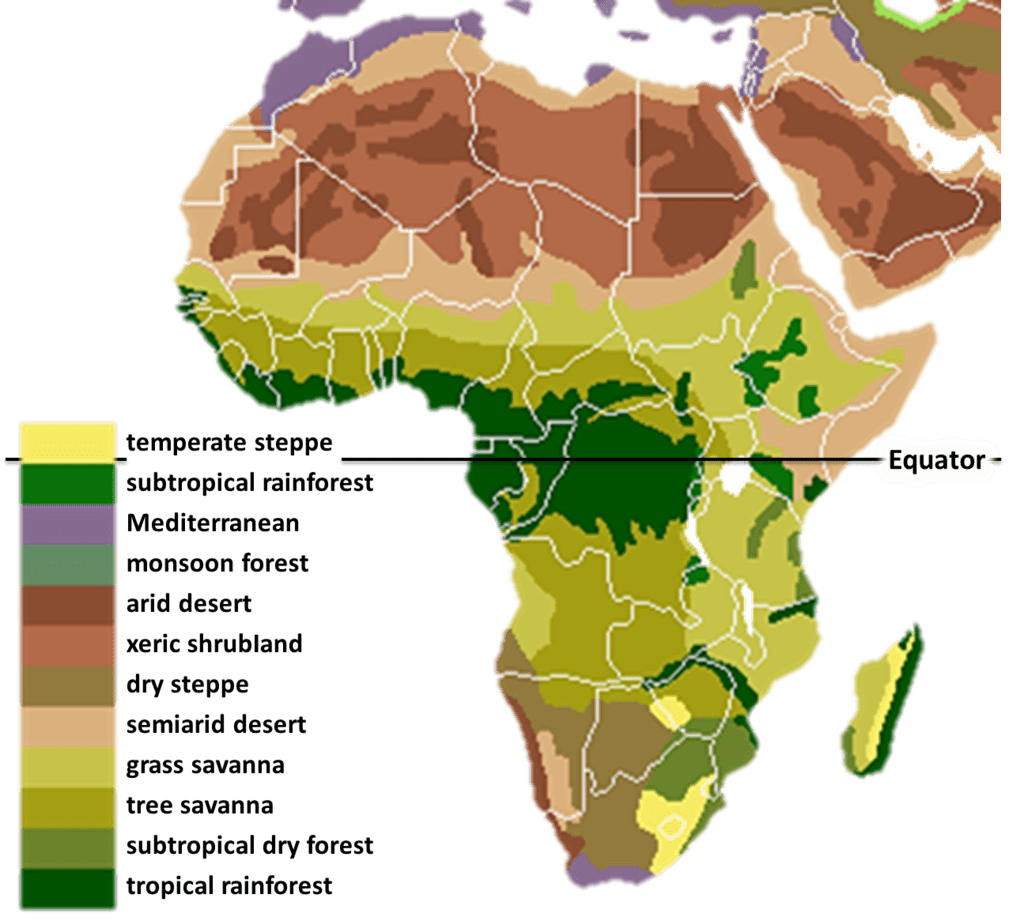

This map by Wikimedia contributor Ville Koistenin shows the vegetation biomes of Africa. The Sahara Desert can clearly be seen in the north with the Sahel and the forested savannah just to the south of it forming a band across the continent between the Sahara and the Central African tropical rainforests. This transitional environment formed the ecological setting for the southern participants in the trans-Saharan trade.

The history of the Mali Empire is deeply tied with the history of the trans-Saharan trade, the name historians give to the phenomenon of the complex of trade routes that crisscrossed the Sahara in the classical, medieval, and early modern worlds. Many histories and treatments of geography, especially popular ones, have traditionally portrayed the Sahara as an impenetrable barrier between the Mediterranean world and the Sahel (the ecological strip of hot-temperate semi-arid land between the Sahara to the north and the African savannah to the south) but now academia pretty universally acknowledges this as false. In premodern times, after all, it was the Mediterranean strip and the Sahel that both were home to Africa’s most prominent urbanized civilizations and crossing between these regions stretches back effectively into prehistory.

The ruins of Garama, one of the central settlements of the Garamantes in modern Libya, by Wikimedia contributor Franzfoto.

Putting aside the eastern part of the continent where Egyptian contact with Nubia for instance is very well-documented and intense from a very early date, the western part of the continent saw the emergence and intensification of trans-Saharan trade starting around the 500s BC and coinciding with the formation of the kingdom of the Garamantes, a state centered in the Fezzan region of southwestern modern Libya, fully ensconced in the Sahara. Classical sources demonstrate that this kingdom guarded trade routes through the Sahara and interacted with Carthaginians, Greeks, and Romans to the north. Using impressive underground irrigation networks known as foggaras, the Garamantes turned the desert into a thriving center of civilization. In book six of Virgil’s Aeneid, published in 19 BC in the reign of Augustus, the Garamantes are boasted about as having been brought under the domain of almighty Rome but wars with them later in Augustus’s reign and in the reign of his successor Tiberius show that this rulership was never complete and even a fantasy. The Garamantes were not nomads but rather had settled communities around the Saharan oases with no more than ten days of travel between entrepôts. This inhospitable desert may not have seemed like the ideal place for a thriving civilization but in fact location was key. The Garamantes were the central connectors between the Mediterranean, the Maghreb, the Nile, Lake Chad, and the Niger River. Their communities relied on desert trade to survive but they also serviced the movement of high-value goods such as rhinoceros ivory from the Lake Chad area to the Mediterranean. Ebony beads and cowrie shells likewise appear to have been trade goods, the latter being especially fascinating because of the history of cowrie shells across African trade as a quasi-currency to facilitate exchange for thousands of years. Human cargo was exchanged as well and the Sahara played host to a long-distance slave trade. The approximately 550 foggara networks in the Garamantian world were the lifeblood of this incredible civilization and as their reign faded in late antiquity, these impressive works of organized infrastructure fell into ruins but the trade networks they pioneered endured long after them. The civilizations to the south of this region would make the trans-Saharan trade a central part of their existence.

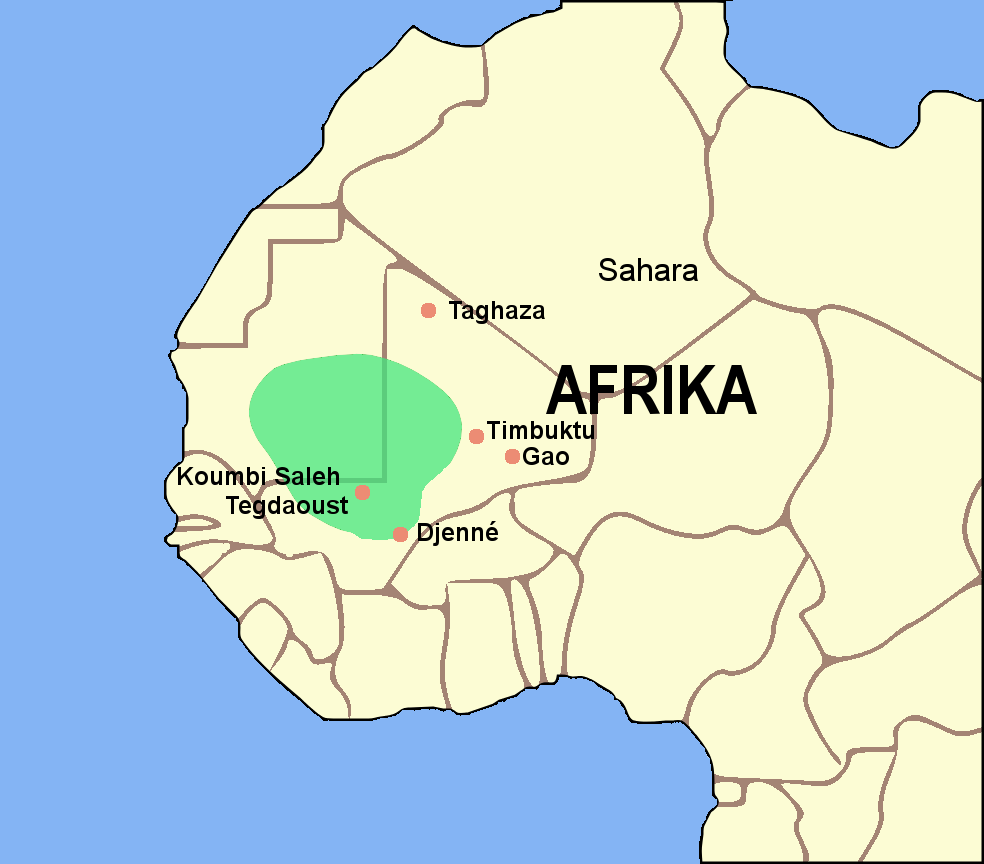

Map showing the approximate extent of the Ghana Empire on West Africa with modern borders by Wikimedia contributor Luxo. Keep in mind that territorial reconstructions of Ghana are approximated from limited sources and that the frontiers of the empire may have been nebulous anyway.

South of the Sahara in the Sahel, an independent Neolithic Agricultural Revolution had occurred as early as around 3000 BC but it was not until late antiquity that an empire in this region caught the eye of the written historical record up north. This was the great imperial predecessor to Mali: Ghana. Confusingly for modern readers perhaps, this classical and medieval empire had no territorial overlap with the modern republic that is named after it, instead being centered in what is now Mali and Mauritania. Around 300 AD, the camel was coming into widespread use in West Africa, allowing for an intensification of trade relations between the region and the Mediterranean, via the Saharan routes. The exact origin of the Ghana Empire and its timing are poorly recorded in the historical record, relying on what references exist in later Arab sources and indigenous oral traditions, but it seems to have been around 300 AD. It is said that the king of the small city-state of Wagadou was named Kaya Magar Cissé and that he and his sons waged a series of conquests over nearby kingdoms, creating the state history would remember as Ghana. In the south of the empire, three distinct regions emerged where there were significant sources of gold for mining and trading. The gold pouring out of Ghana on the trans-Saharan trade gave the Ghanaian kings the title of “the lords of the gold” and all gold discovered entered into royal property. In the 600s AD, the Roman coast of North Africa gave way to an Islamic coast of North Africa as the Umayyad Caliphate rapidly expanded west, bringing the Ghanaians a new primary trans-Saharan trading partner. As in earlier centuries, the trans-Saharan trade continued to include a slave trade (though it was not at the population-devastating scale it would become from the 1500s onwards) but in the medieval world gold was king. The Ghanaians built their capital at Koumbi Saleh in what is now southeastern Mauritania. This city had a population of between 15,000 and 20,000 which was small compared to the great cities of the medieval world but thriving by the standards of the rugged Sahel and Arab visitors were impressed by its architecture and wealth. From this political center, gifts of luxurious wealth were given to nearby smaller states to exert influence over them. An almost certainly exaggerated Arab source claims that Ghana had an army of 200,000 men, which at the very least shows that the military power of this West African state was significant enough to wow visitors from the Islamic world.

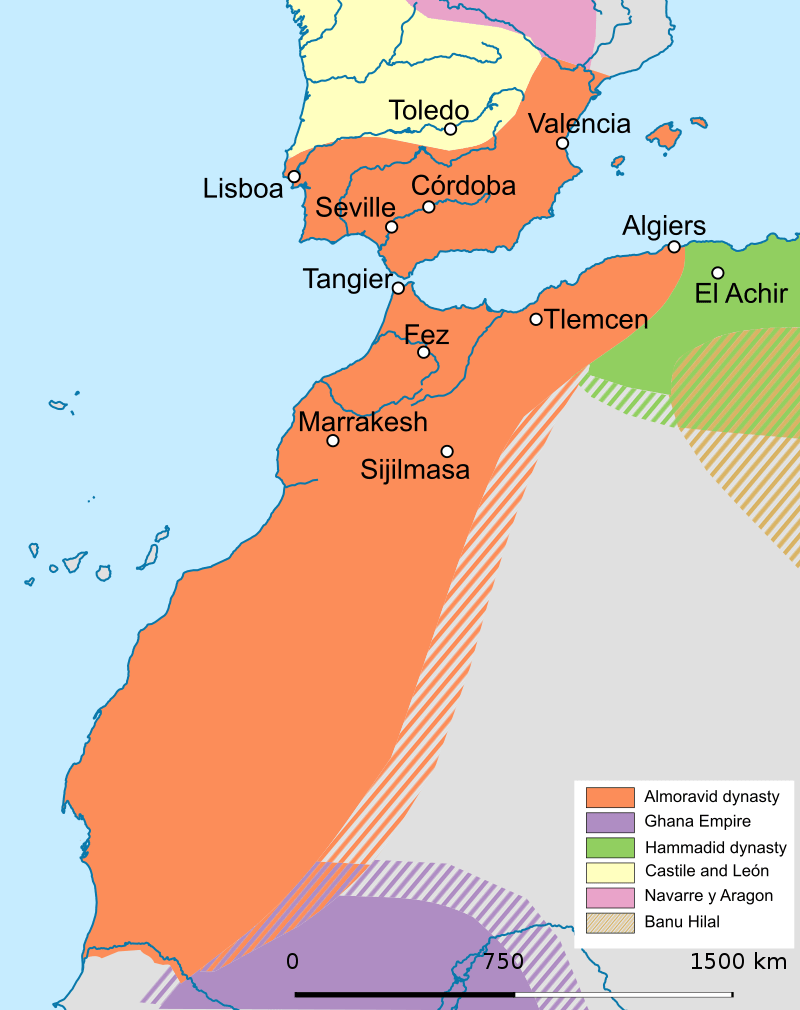

A map showing the Almoravid dynasty at its maximum extent in the 1000s with Ghana bordering in the south. Map by Wikimedia contributor Flaspec.

In the 1000s AD, an expansionist Amazighi Moroccan state known as the Almoravid dynasty captured territory down the west coast of the Sahara such that it became a trans-Saharan empire itself, threatening Ghana. Some conflict between the two occurred but the details are unclear, however the Almoravids did not succeed in taking over or destabilizing Ghana. In the next century, the Almoravid state destabilized and collapsed but the Islamic presence in the Sahel was not going to go away. Islamic court officials often proved to be learned and well-studied experts who were good at their jobs and Ghanaian kings employed more and more of them. Soon the rulers themselves converted. Foreign conquerors could not bring Islam to West Africa but political interests, trade connections, and the genuine intellectual attractiveness of the religion could. Like Mali afterwards, Ghana was never a homogeneously Islamic state and Islam was a practice of the elites in the urban spaces while most people still practiced indigenous West African religions. By 1200, as Ghana emerged as a participant in the Islamic world, it was more open to foreign influences and its trade position had become the southwestern extremity of a great network of mercantile connections that extended across Afro-Eurasia, including the Silk Road. The late medieval world truly was an age of globalization in the Old World. But Ghana’s ascendancy was to end rather quickly. A wave of dry conditions and political in-fighting destabilized the empire in the early 1200s and the formerly multi-ethnic hegemon splintered into a miscellany of different states.

The Mali Empire was born from this wake, but not immediately. The founding of the Mali Empire is the subject of a very culturally important historical-mythological tradition preserved in the form of a great oral epic memorized and passed down by the griots. In recent centuries, this narrative was copied down and translated by French ethnographers but the history it relates to was commented upon by medieval Arab sources as well much closer in time to the events described. We therefore can conclude that its protagonist, Sundiata Keita, was likely a historical figure even if aspects of the Epic of Sundiata are certainly fantastical. Following the fall of Ghana in the early 1200s, one of the prominent kingdoms that formed in its wake was Sosso, which according to the epic, under the reign of king and sorcerer Soumaoro Kanté, conquered many lands including those of the Malinke people. Sundiata, a crippled-at-birth Malinke boy who had overcome his difficulties and learned to walk in childhood and even become a respected warrior, vowed to liberate his people from their tyrannical oppressor. Leading a coalition, he overthrew the Kingdom of Sosso and became the first mansa of a new empire, Mali, around 1235. His dynasty, the Keita dynasty, would be the ruling family of the Malian state throughout its history. It’s unclear if Sundiata’s empire-building achievements were actually achieved in his reign or if he was attributed the achievements of several different actual rulers together.

Here I will be following the royal history more or less as related by Moroccan historian Ibn Khaldun writing in the later 1300s but keep in mind that different sources sometimes give slightly different Malian royal histories, especially with lesser-known mansas. It is somewhat unclear when conversion to Islam happened as Ibn Khaldun for instance claimed the Malinke leaders were already Muslim before Sundiata but the Epic of Sundiata portrays the titular mansa in the role of a West African polytheist. Islamic names appear in historical records as the very sons of Sundiata: Wali, Wati, and Khalifa, who each ruled in succession after him. In fact, the Keita dynasty would go on to claim lineage from Bilal, the Ethiopian who became a companion of the Prophet Muhammad and the first muezzin or giver of the call to prayer, clearly an attempt to establish Islamic legitimately via an African lineage, even though the relevant ancestor was from across the continent. As noted with the religious diversity of the late Ghana Empire, Sundiata being a Muslim or a practitioner of traditional West African religion are both plausible premises. It is also possible that syncretism blurred these boundaries and framing an either/or dichotomy like this is missing the point.

Sundiata’s third ruling son Khalifa was deposed and the man who replaced him was Abu Bakr who was then himself deposed by a freed slave named Sakura. Sakura went on the hajj and was killed on his return, restoring the throne to the Keita dynasty with a mansa named Qu whose son then succeeded him under the name of Muhammad. According to the account of al-Umari, which I opened this article with a quote from, Mansa Musa’s predecessor, which would have been Muhammad Ibn Qu according to the list of rulers given to us by Ibn Khaldun, sailed off in an expedition into the Atlantic and disappeared. This ended the lineage of rulers directly descended from Sundiata but the Keita dynasty was preserved through the ascension of a cousin, Mansa Musa. A quick note on the Atlantic expedition here: it often appears online that this expedition was undertaken by a mansa named Abu Bakr II (no such ruler of Mali existed) and claims sometimes indicate that the Malian fleet landed on the coast of Brazil and even colonized it, something which is supported by neither the historical or archaeological record. If Muhammad Ibn Qu really did sail off into the Atlantic, he seems to have died at sea. This is one of many areas of premodern history where popularly distributed fun facts on the internet are simply inaccurate.

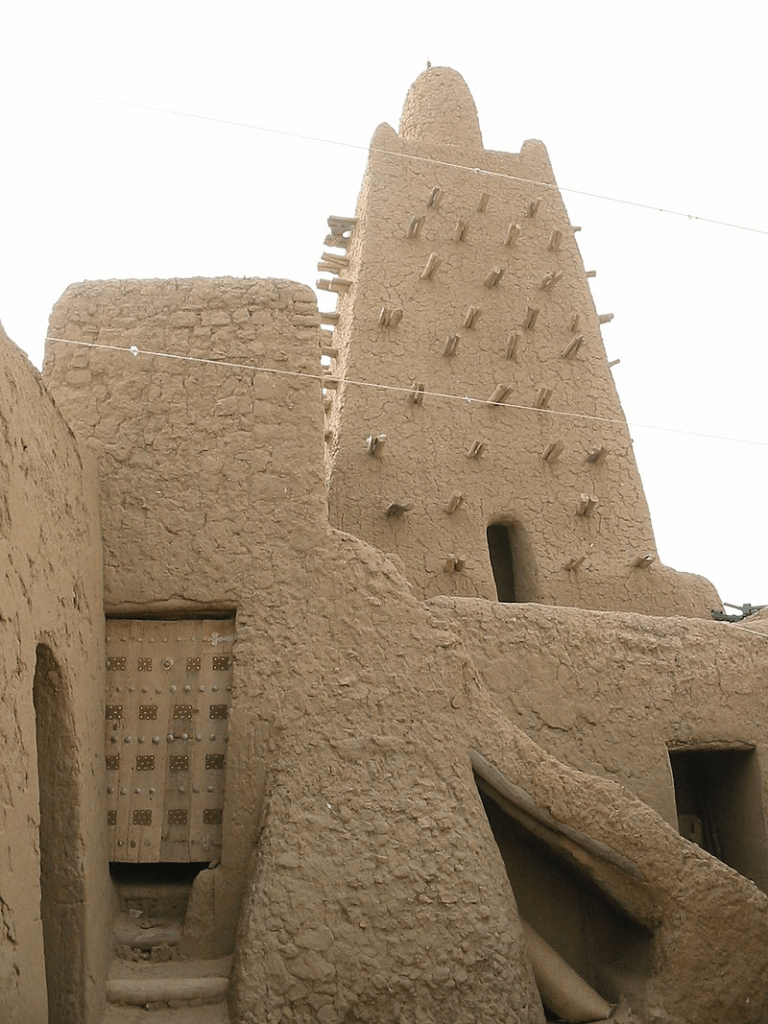

The Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu, Mali, built in the reign of Mansa Musa as part of his new Islamic center in the city. Photo by Wikimedia contributor KaTeznik.

Around 1312, Mansa Musa Keita I ascended the throne of Mali and began the reign that would be what is generally regarded as the empire’s height, though it’s possible the empire’s size and wealth actually peaked somewhat later and Musa’s reign is just the best-recorded because of the impression his famous hajj left on the outside world. Musa’s hajj was nothing short of extraordinary but it was far from his only lasting impact. With the impression it left on much of the rest of the Islamic world came an increasing entanglement with that world, which was certainly part of the intention. Musa was a patron of Islamic learning and constructed a number of significant monuments that still stand today, especially in the city of Timbuktu where he established several such structures, including what is commonly called a university (actually a collection of madrassas or schools of Islamic learning) and most famously the Djinguereber Mosque, designed by an Andalusian (that is, from al-Andalus, the name for the then-Islamic-ruled regions of modern Spain and Portugal) architect Musa had recruited named Abu Ishaq al-Sahili. Timbuktu was never the capital of the Mali Empire but it did become an international center of it as an arena of trade and internationalism, emerging as both a major way-station on the trans-Saharan trade and as a regional center of pilgrimage. Many specialists from the wider Islamic world arrived in Mali but likewise many Malians studied abroad in Morocco and other places. Aesthetically, Mali’s architecture took on influences from the wider Islamic world, such as the new royal palace, also designed by al-Sahili, adorned with a dome. It is here at the height of the empire that we will stop to explore its various economic facets.

Industry and Export

In setting out to write articles on this site, most of the time choices in topics are determined by what I know something about but wish to know about better, giving me an excuse to research. I wanted to explore the medieval Malian economy and how it achieved its impressive scale and exuberance. In looking into this, I realized early on that I was not sure how medieval national economies were measured and, frustratingly, while I can find much literature on medieval Malian industrial and trade practice as I’ll cover below, holistic treatments of the economy in terms of scale are not particularly prevalent. Nevertheless, I think some exploration of how medieval economies are reconstructed is useful to understanding why we know what we know. A well-studied contemporary civilization to the late medieval Mali Empire is England where studies have reconstructed GDP and collected significant historical records on pricing data. GDP or gross domestic product is the most common way of measuring the “size” of an economy in the modern day and it represents the total monetary value of all final goods produced in a state, generally per year. The concept of GDP is theoretically just as applicable to premodern states as to modern ones, but comes with the difficulty that the data for approximating it is highly incomplete. The most significant industry was agriculture and so agricultural output is one of the most notable modulating factors of medieval GDP, which of course tends to scale with population. That said, the mechanics of GDP mean that high-value goods contribute more highly per unit to the size of the national economy. On top of that, a further caveat is that the relationship between the price of goods and actual money is debated regarding the medieval world. In the modern world, more money in circulation tends to mean an inflation in prices but in the medieval world, these forces could be more decoupled for several reasons. Firstly, not all transactions took place using a traditionally defined currency and barter occurred all the time. Secondly, individual economic actors did not have the same access to widespread pricing and industry data and so could be far more varied and disconnected from each other. Recorded pricing data from England seems to suggest that medieval goods prices fluctuated frequently and locally. Population estimates on the Mali Empire are difficult to ascertain but it is safe to say that it was larger and more populated at its height than most states in, for example, Europe at the time. Most of its population did not work in the luxury industries but in agriculture, however, industries like gold boosted the size of an already massive economy significantly, Mali’s gold in particular accounting for about a third of global supply at the time. The Mali Empire was most certainly one of the largest national economies in the world at its height.

Let’s start our exploration with the most defining industry of the last 12,000 years of human history: agriculture. West African agriculture was not dependent on one staple crop but from a whole slew of raised plants and animals. In this region, the domestication of animals, specifically cattle which were independently domesticated in sub-Saharan Africa separately from in Asia, actually predated plant-farming and in the time of the Mali Empire, and indeed today, pastoralism remained a widespread lifeway. In the same capacity as the cereal grains of the Near East, two crops dominated the West African grain economy: pearl millet (Cenchrus americanus which despite the name is not native to the American continents) and African rice (Oryza glaberrima), both domesticated from wild plants in the region and cultivated for millennia before the Mali Empire. Numerous other animals and plants were raised in less important capacities and wild hunting and gathering happened as well. Sedentary society encouraged the development of processed food products such as boiled foods, sauces, and communal food and beer as continue to characterize West African food today. Another interesting usage of plants is intentional forest management for various reasons such as environmental resources as well as more direct things like wood and even the cultivation of the banana which is actually native to maritime Southeast Asia but spread to Africa via the Indian Ocean trade and reached the region by around 500 BC, thriving especially in the rainforest environments to the south. Overall, as with most pre-industrial civilizations, the majority of the population was involved in agriculture to some extent, especially as, despite the existence of major cities that are often emphasized as the centers of the history of the empire, the majority of the Malian world was deeply rural.

The Mali Empire, like most powerful medieval states, widely practiced a form of slavery and, as the titan of the trans-Saharan trade in its time, an international slave trade passed through its markets. Discussing slavery in the Mali Empire is made somewhat difficult because of the limitations of our sources combined with a seeming internal diversity. As both a multiethnic and multireligious empire, attitudes to slavery and the rights of the enslaved could vary a significant amount, as could answers to the question of how differentiated slaves were from other members of low laboring classes. In general, we should understand Malian slavery as being impacted by indigenous practice predating the empire, Islamic attitudes to slavery, and the external expectations of trading partners that the empire exported to. Unlike the chattel slavery familiar to American readers, pre-colonial West African and Islamic forms of slavery were not restricted to certain ethnic groups and slaves could often, if freed, achieve considerable social mobility (remember that even the briefly ruling early mansa Sakura had been a freed slave). Islamic attitudes to slavery were largely developed out of older Roman practice with people able to enter into slavery from capture, to repay debts, or even voluntarily. Within the medieval Arab world, dhimmi (those tolerated non-Muslims, generally Jews and Christians, under Islamic rule) were not taken as slaves if they lived peaceably and within the confines of the social restrictions and obligations placed on them and Islamic law forbid the forceful enslavement of another Muslim. As such, Islamic states generally imported their slaves from Dar al-Harb, the non-Islamic world. Africa became a significant frontier for this, both down the eastern coast of the continent and by the trans-Saharan trade. For those slaves not intended for export and used within the Mali Empire, they were able to have rights to their own property ownership and money, though resources and products produced by them tended to go completely to their owners. Slavery was therefore not so much in the sense of unpaid labor but of lack of legal agency of the enslaved in choosing to do work. Hypothetically a slave could be put into a very prestigious role and be compelled to do it while owning a lot of property and at times this appears to have happened in the upper echelons of society. Naturally though, this was not the experience of most people subject to the cruel practice of human ownership. Certain industries ran heavily on slave labor. While agriculture was widely practiced by the traditional free population as well, in certain places slaves carried out specialized labor. For example, at oasis settlements that formed key way-stations in the Saharan crossing, agriculture required to produce food was difficult and required using very limited resources in a way that required intensive maintenance. As these were already hubs for the slave trade, slaves remained there under the yoke of nomadic tribal masters growing food plants such as date palms and cereal grains and raising camels. The Amazighi and other peoples who largely managed these desert outposts often signaled social differences through their traditional wearing of the turban with varying styles between enslaved and free.

A photograph from modern Timbuktu, Mali, showing salt slabs at market. This traditional means of carrying and trading salt goes back to the Ghana and Mali empires. Photo by Robin Taylor on Flickr: salt from Timbuktu | Robin Taylor | Flickr

Slavery was also tied up with that other great source of mineral wealth of the Mali Empire: salt. Unlike today’s world in which salt is cheaply produced in industrial quantities and considered one of the most basic of seasonings, in the medieval world salt was a luxury resource, requiring an intensive geographically restricted process of extraction and refining, followed by what could often be a very long-distance trade. In the days before the colonial spice trade, it was also at times one of the accessible food flavorings and, considering the lack of refrigeration, could be necessary for keeping food for an extended period of time. To the south of the Mali Empire on the savannah, salt was an essentially inaccessible commodity in the landscape and it required importation. The south was also where the Malians mined their gold. Where salt was found littering the ground like rocks was in certain parts of the Sahara to the north of the empire. As such, the core of the empire sat between its two greatest sources of geological wealth and was able to use one to dominate the trade of the other. Salt was carried south to sustain the gold-mining workforce while the gold produced from these mines would pay the desert traders that sustained lucrative commerce on behalf of the empire. In the Ghana and Mali empires, the royal treasury would keep not only a stock of gold but also of salt and in rural parts of the empire it often functioned as a sort of currency by weight. Unlike the gold mines, however, the royal estate had a hard time keeping a monopoly on the salt mines. Both royal and privately owned mines employed enslaved labor forces in extraction and the goods were moved in large blocks to market. The Malian royal capital of Niani, located in the south, did not have a competitive position on the Saharan salt deposits and so more northern-oriented centers like Timbuktu had elites that played their own important roles in the salt economy. Regardless, the Niger River was the great internal artery of trade east-to-west in the empire and goods in one part of the empire could propagate to another easily along it, especially as all the major urban centers were clustered around it, the price of salt doubling according to Arab travelers as it moved southwest across the empire.

Amazingly the symbiotic relationship between gold and salt merchants in West Africa was such that they could apparently conduct trade with a party in absentia. The system of “silent trade” involved one bringing goods and leaving them where the other could assess a proposed trade even if they both could not be there at the same time. In the 900s AD, an anonymous Arab writer recorded an eyewitness account of this happening in what was then the Ghana Empire. “Sudan” here refers not to the modern country but to sub-Saharan Africa generally and is what it is called in medieval Arabic texts.

Great people of the Sudan lived in Ghana. They had traced a boundary which no one who sets out to them ever crosses. When the merchants reach this boundary, they place their wares and cloth on the ground and then depart, and so the people of the Sudan come bearing gold which they leave beside the merchandise and then depart. The owners of the merchandise then return, and if they were satisfied with what they had found, they take it. If not, they go away again, and the people of the Sudan return and add to the price until the bargain is concluded.

Camel caravans moving salt and other goods could be colossal, numbering at times in the thousands and each camel might carry two salt blocks weighing about 90 kilograms each. Other goods that moved on this trade included gold, leather, skins, and ivory, all of which moved north to the desert merchants and the kingdoms that lie beyond them. And yet another was spices, as demonstrated in an early-1200s text Le Roman de la Rose, lines 1389-1394, by French poet Guillaume de Lorris, translated to English by Carol Symes. Here various spices are described in an idyllic garden.

In that orchard, many a spice:

Studded cloves and liquorice,

Grain of paradise, newly come,

Zedoary, anise, cinnamon;

And many a spice delectable

Good for eating after table.

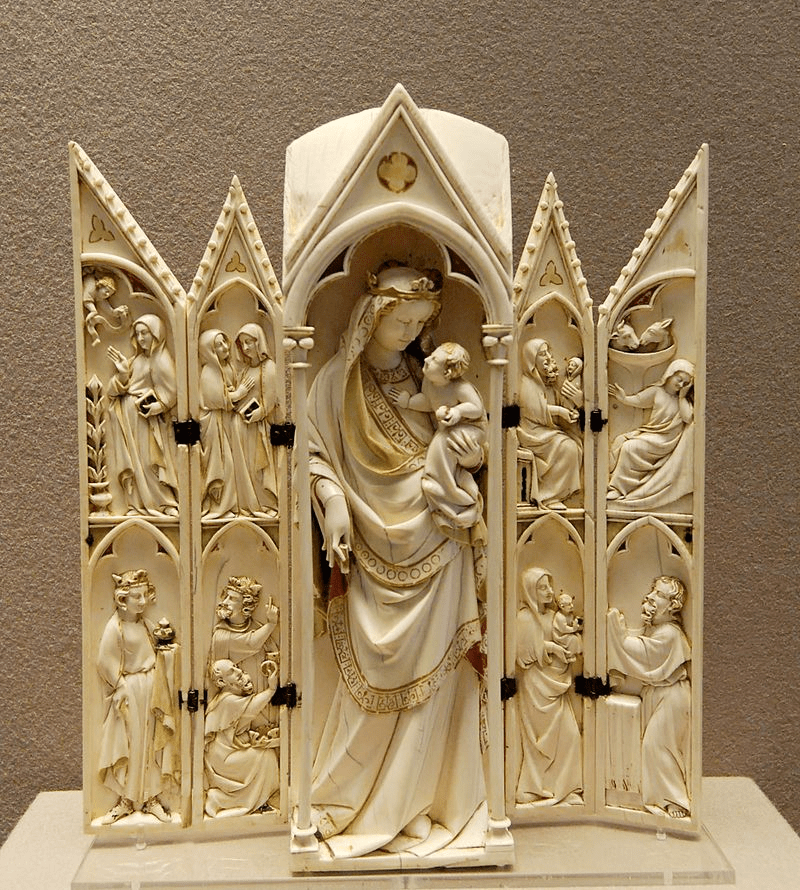

The “grain of paradise” here is Aframomum melegueta, the melegueta pepper, a relative of ginger native to West Africa that starting in the 1200s became a favorite food seasoning in the French and Burgundian courts. Not only was the Islamic world taking in the wealth of West Africa but the late-medieval explosion of the trans-Saharan trade brought its luxury goods as well to Europe, where they could be found in abundance in prestige objects. Of particular note was elephant ivory which became a prized carving material for especially religious objects and displays of wealth for nobility. These carvings exhibit the late-medieval Gothic artistic style in lovely miniature.

Carved around 1350, this ivory tabernacle from France centers the Virgin Mary with scenes from the Nativity of Jesus. Photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen on Wikimedia.

The Mali Empire’s incredible wealth made it a juggernaut in the interconnected world of late-medieval Afro-Eurasia and its influence within Africa, the Islamic world, and Europe was incredible, Mansa Musa’s hajj being merely the most dramatic tip of the iceberg. But states and empires are temporary things and, with Mali’s decline, West Africa would change forever in ways that would make the trans-Saharan trade dry up like the desert itself.

Guns and Ships

Around 1337, Mansa Musa Keita I died, leaving behind a vast empire that had attained new territories, established its place as a foremost center of scholarship, and attained legendary recognition as the richest land in the world all during his reign. These things did not go away upon his death but the weaknesses under the surface came to light. Mali had never had a clear succession system and much of the rest of the empire’s history would be plagued by the familiar problem of dynastic conflict. For the rest of the 1300s, however, the Mali Empire remained indisputably the greatest power in West Africa. That said, Arab traders began looking for new trading partners to break down the Malian monopoly. One of these was the Kanem Empire, centered around Lake Chad to the east. The regional West African elites under the Mali Empire who had built up their own local influences on the peripheries of the state also became potential partners increasingly distinct from the royal center.

In 1415, Portuguese forces under one Prince Henry the Navigator captured the Moroccan outpost of Ceuta and began a new age in the history of continent as Portugal began to regularly ply the coasts down West Africa. Until his death in 1460, Henry would be a leading force in encouraging his small country to expand its presence in West Africa with the hope of claiming some of the lucrative wealth of the trans-Saharan trade for itself. Instead of making desert crossings though, the Portuguese would come by ship. The Atlantic trade was already a thing but developments in new European shipbuilding would make it a genuinely deadly competitor to the inland trade practices that had defined the region. It is in this period as well that eyewitness Portuguese sources begin to appear in the history of the Mali Empire, the earliest being from 1455 when a Venetian slave trader hired by the Portuguese, Alvise Cadamosto, sailed up the Gambia River and into the empire. Other expeditions by other navigators would continue at some frequency, largely seeking a particular resource that the Portuguese had increasingly taken interest in a certain trade good they had encountered in their new Moroccan holdings: African slaves. As the Portuguese arrived, local elites in the Senegambia region began to recognize the potential of this maritime market and that they might compete with their previously wealthier inland counterparts who had participated in the trans-Saharan trade. The Atlantic slave trade, which would balloon into one of the most horrific processes of human suffering in the history of the world, was beginning.

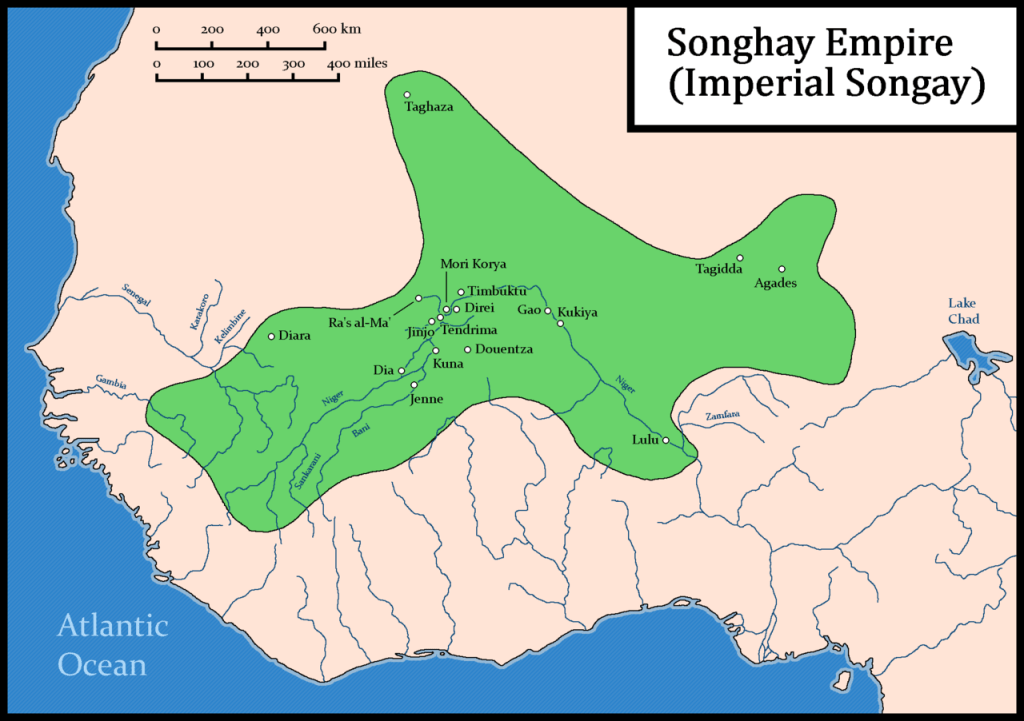

A map of the Songhai Empire at the height of its power around 1500 by Wikimedia contributor HetmanTheResearcher.

Meanwhile, inland rivals were beginning to pick at the Mali Empire. From the north, raiders of the Tuareg people invaded the region in 1433, establishing frequent presence from the 1460s onwards and at the same time the Mossi people south of the Niger river invaded northward into the empire. The wealth of Mali was becoming bait for external invaders while political stability made the empire vulnerable. But the greatest political threat would be the rise of a new empire alarmingly close to Mali’s core. The Songhai were a Nilo-Saharan-speaking people group that had been located on the Niger River since at least the 800s AD when they controlled a small kingdom there contemporaneous with and neighboring the Ghana Empire. With the explosive territorial rise of Mali, the Songhai had been subjugated and took on an important role facilitating river transport within the empire’s trade and were thus capable of resisting the state powerfully at times. Over the chaos of the 1400s, the Songhai power base became something more like an independent state centered on their capital of Gao in modern Mali as imperial control waned. Like many of the people groups in the region, the Songhai traditionally practiced raiding as a form of warfare but that would change. Coming to power in 1464, Sunni Ali of Songhai set his mind on military reforms and territorial expansion, adopting armored cavalry of the sort that was used in the Arab world and building the first military fleet in the West African region, deployed on the Niger to control and project power down the river. Simple as these innovations seem, they created a new regional power in the middle of a declining empire and over the next few years, Songhai hegemony expanded until, in 1468, Mali itself was a rump state paying tribute to new Songhai overlords to the northeast. Sunni Ali would rule until 1492, waging conquest after conquest victoriously and without defeat until Songhai emerged as perhaps the largest indigenous empire in West African history.

While it is easy to write off the Songhai Empire as the relatively short-lived successor to the more famous Mali Empire, it is important to realize that its success relied on innovation in a changing world. Like previous empires in the region, the rulers were Islamic, as clear from their names, but some like Sunni Ali appealed directly to indigenous folk religion, such as being considered a powerful sorcerer in the local magical traditions. Defeated armies would be integrated into the imperial forces and resistance would sometimes be met with incredible violence but local rulers who were willing to pay tribute could continue to have a place. The mansas of Mali thus, amazingly, continued to rule once their empire had been replaced, now just as regional authorities under the Songhai juggernaut. Conquering up the Saharan trade routes, Songhai took a direct hold on the major centers of the trans-Saharan trade in a way the Mali Empire had not entirely done. Timbuktu hit its late-medieval height at around 100,000 people, the center of multiple crisscrossing trade routes and still home to its center of Islamic scholarship that Mansa Musa had founded. The capital of Gao was a similar size. Cities boomed as the Songhai rulers invested in more advanced irrigation systems on the Niger and took a more direct interest in urban planning. But the reality was that the trans-Saharan trade was declining and external factors were about to spell the end of West Africa’s incredible medieval prosperity. Under the reign of Askia Muhammad I, a former-commander-turned-usurper who ruled from 1494 to 1528 and was far more traditionally and puritanically Islamic than his predecessors, the army was fully professionalized and the empire pushed to its territorial extent, largely driving southeast. One region of the former Mali Empire remained elusive to the Songhai however: the Senegambia region on the Atlantic coast, which was increasingly becoming under the sphere of Portugal, a power that barely had a foothold in West Africa but which was certainly the only capable military threat there facing Songhai, or so the Songhai rulers thought. Portugal was siphoning off the gold trade from the Saharan caravans and transporting far more efficiently by ship than by camel. Askia’s conquests towards the south where gold was mined may have been a response to this troubling issue.

After Askia’s death, the power of Songhai declined as claimants struggled to agree on who would replace the great usurper king. For decades it gradually shrunk and in 1586 was effectively divided in two between fighting brothers. The crack of external gunpowder would spell the end of the great empires of the Sahel amidst this opportunity. Ahmad al-Mansur was a member of the Saadi dynasty and sultan of Morocco from 1578 to 1603. The direct neighbor of Spain and Portugal, both of which now wielded global empires, he saw a world in which his North African state would need to compete in this new age of rising European powers and claim territorial power for itself. His personal writings show ambitions both at reconquests in Iberia and colonies in the Americas, but in history as it played out, his imperial successes were in West Africa. In a campaign that lasted from 1590 to 1591, 4,000 Moroccan soldiers armed with muskets crossed the Sahara and faced the army of Songhai, arrayed with 30,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. Fighting with spears and bows, however, the Songhai forces were cut down in a bloodbath as the Mediterranean age of gunpowder bore down on their medieval armies. For the first time since the Almoravids six centuries before, a Moroccan state attempted to conquer West Africa and this time it succeeded. Local rulers became direct subjects to the Arab state, including the still present mansas of Mali, who would continue into the 1600s under the Moroccan thumb.

This was all almost beside the point though. In the early 1600s, the coasts of West Africa were dotted with outposts by the Portuguese and Dutch and the explosion of the maritime trade had moved the center of economic gravity away from the Niger River and towards the Atlantic coast to the west and south. Gold, ivory, and other goods sought out of the region were increasingly exported by new upstart kingdoms that grew rich off these new hubs and had no particular need for crossing the Sahara. And unfortunately the rulers of these states learned quickly that what the Europeans wanted more than anything were captured members of other African peoples who could be sold off into slavery. The demand was so great that entire societies were uprooted and exported, generally to warm regions of the Americas, where a new form of racialized slavery that treated humans like beasts of burden with no rights whatsoever was becoming the dominant mode of economic activity in the production of cash crops. The age of great empires in West Africa was over, as was the age of the spectacular wealth of Mansa Musa and those like him, who dominated an inland desert trade system that allowed the region to become a key and respected part of the larger world. In its place was the maritime trade and the Atlantic crossing and all the horrific legacies associated with such.

Further Academic Reading

- Alexander, J. “Islam, archaeology and slavery in Africa.” World Archaeology 33, 1, 2001: 44-60. Islam, archaeology and slavery in Africa (psu.edu)

- “Al-Umari’s Account of Mansa Musa’s Visit to Cairo,” in World History Commons, Al-Umari’s Account of Mansa Musa’s Visit to Cairo | World History Commons [accessed June 29, 2024]

- Baker, David. “The Ghana Empire: West Africa’s First Major State.” Big History Project 950L, 2015. https://www.oerproject.com/-/media/BHP/PDF/Unit7/U71The_Ghana_Empire_2015_950L.pdf

- Cartwright, Mark. “Mali Empire.” World History Encyclopedia, 2019. Mali Empire – World History Encyclopedia

- Cartwright, Mark. “The Salt Trade of Ancient West Africa.” World History Encyclopedia, 2019. The Salt Trade of Ancient West Africa – World History Encyclopedia

- Cartwright, Mark. “Songhai Empire.” World History Encyclopedia, 2019. Songhai Empire – World History Encyclopedia

- Casson, M. and Casson, C. “Modelling the medieval economy: Money, prices and income in England, 1253-1520.” Money Prices and Wages: Essays in honour of Professor Nicholas Mayhew. Studies in the History of Finance, 2015: 51-73. https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/49603/3/Medieval%20Modelling5.pdf

- Guérin, Sarah M. “Exchange of Sacrifices: West Africa in the Medieval World of Goods.” The Medieval Globe, 3, 2, 2017: 97-123. Exchange of Sacrifices: West Africa in the Medieval World of Goods (jhu.edu)

- Haour, Anne and Moffett, Abigail. “Global Connections and Connected Communities in the African Past: Stories from Cowrie Shells.” African Archaeology Review 40, 2023: 545-553. Global Connections and Connected Communities in the African Past: Stories from Cowrie Shells (springer.com)

- Ly-Tall, M. “The decline of the Mali empire.” General History of Africa IV, 1984: 172-186. https://repository.out.ac.tz/406/1/Vol_4._Africa_from_theTwelfth_to_the_Sixteenth_Century_edior_D.T.N1ANE(FILEminimizer).pdf#page=196

- MacEachern, Scott. “Two Thousand Years of West African History.” African archaeology: A critical introduction, 2005: 441-466. https://www.academia.edu/download/63478392/African-Archaeology20200530-23306-a5zi43.pdf#page=457

- Mattingly, David. “The Garamantes of Fazzan: An Early Libyan State with Trans-Saharan Connections.” Money, trade and trade routes in pre-Islamic North Africa, 2011: 49-60. https://www.academia.edu/download/86099463/Money_Trade_and_Trade_Routes_online.pdf#page=53

- Niane, D. T. SUNDIATA: an epic of old Mali. Translated by G. D. Pickett, Pearson Education Limited, 2006. Sundiata.pdf (scarsdaleschools.k12.ny.us)

- Oulhadji, Mohamed. “The West African Medieval Empire of Mali (13th-15th centuries).” 2018, Ahmed Draïa University, Adrar, master’s thesis. The West African Medieval Empire of Mali (13th-15th Centuries).pdf (univ-adrar.edu.dz)

- “The Cresques Project.” The Cresques Project – Panel III

Living in the Longue Durée is part of the History Nerds Network, a group of friends who together make history content online. Check out our Discord server here if you’d like to chat with us: https://discord.gg/dzdrzUpKeG You can also follow for post updates on the Facebook page ( https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61559902349797 ) or on Instagram at @livinginthelongueduree .

Consider supporting my time and money investment into research on Patreon if you want to allow articles like this to maintain their quality and regularity: Living in the Longue Durée | A thoughtful and eclectic history blog. | Patreon

Leave a comment