You and your clan have been walking for days through the warm chapparal of the Konya Basin, the occasional hunting of small game and a collection of edible plants keeping you sustained. You’re a bit hungry though and your thoughts swirl around processed wild grains. Your traveling companions remark that it has been a while since you visited the village and they are interested in catching up with the others who spend time there more permanently, using the local trade language that some of your group are more familiar with than you. Hunted game will be exchanged for plants and ritual specialists will be sought out to manage your more spiritual concerns.

The sound of human voices over a nearby hill signals you are close and then it comes into view: a small settlement surrounding several strange circular structures with great carved stone pillars. This site is not unique in the region but it does have a very different state of being from the more mobile lifeways you participate in most of the time. Nomads and sedentary people there find common aims through productive exchange, a sort of specialization. The fact it’s the center of the local economy is evidenced by the scale of construction: a large number of people worked together to erect the monuments.

This is how it’s been for generations but time will tell that you are at the start of one of the fastest transitions in human history.

The Blink of the Geological Eye

Our genus Homo is considered to have split off from Australopithecus around 2.8 million years ago. For the vast majority of this time, our ancestors lived off of wild resources and made comparatively simple stone tools. Hominids carved out a unique ecological niche for themselves but still had little impact on the planet overall. Around a million years ago, Homo erectus began to take command of fire. The ability to chemically break down food to maximize its nutritional potential (and kill pathogens), the ability to modify land on large scales through burning, and the ability to extend waking hours through a portable light source so as to make time for exercising social cohesion all greatly increased the power that members of genus Homo had over the surface of the world and its inhabitants. Based on a partial skull and jaw from the site of Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, we are able to date anatomically modern Homo sapiens to at least around 300,000 years ago. Essentially all humans were hunter-gatherers for 96% of the time our species alone has existed. And then, 4% of our species’s history ago, some of our cohort began to farm. The last 12,000 years represent the fastest period of rapid lifeways change in our ancestral story and while on initial contact with that number, it looks like a long time, it’s important to remember its percentage amidst the whole.

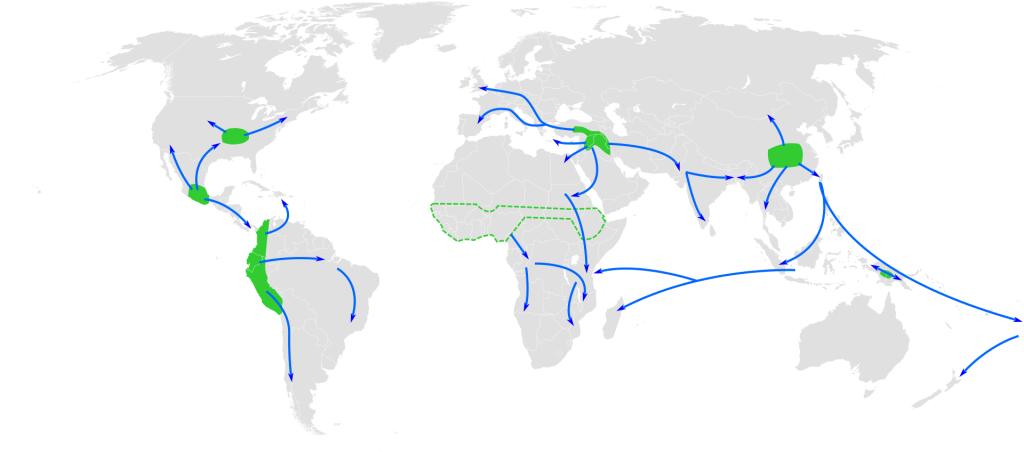

The way this story has traditionally been told is simple: humans began to farm. In several isolated regions of the world independently, within a few thousand years of each other, humans began a complicated relationship with plants and animals, using them in manners that inadvertently selected over time for features that benefitted the humans making use of them. The revolution in food production necessitated sedentism, people choosing to live in one place rather than moving, creating villages. Food surplus led to specialization as more of the population could focus on other tasks and the need for coordinated leadership demanded complex institutions. The end result of this was the city and civilization and history followed.

A map of the places where agriculture was independently invented, made by Wikimedia contributor Joe Roe. The seven regions where the development happened show there are at minimum seven different stories of how a Neolithic Agricultural Revolution can take place.

But newer developments in the study of the human story have come to nuance this way of looking at the world. Did agriculture really lead to sedentism or did people who lived increasingly sedentary lives simply tend to make the transition to agriculture? Is agriculturalism a prerequisite to the development of complex societies or will simple environmental surplus allow for it at times? Is domestication really intrinsically part of cultivation or might there be a deep past of cultivated plants that never show domesticated traits in the material record? Increasingly, the answers to every one of these insinuations seems to be yes, sometimes. It’s traditional to center the discussion on the Near East, where the transition appears to have happened earliest, and we will be doing this in our focal discussion today, but likewise it is something of a mistake to treat the Near East in isolation without comparative examples from elsewhere in the world when trying to divine a pattern. The recognition of this has been part of how the discussion has been reframed but another aspect comes from the excavation of a dramatic new site since 1995 in the Near East itself: Göbekli Tepe.

The Konya Basin at the End of the Ice Age

The landscape of the Konya Basin as taken by Wikimedia user Zhengan.

The Konya Basin is a region in what is now southeastern Turkey which sits raised at over a thousand meters of altitude and is characterized by a dry heat. Over the course of the Pleistocene Epoch (which geologists define from about 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago and which is popularly synonymized with the “Ice Age”), the area was often inundated with significant lakes, somewhat salty owing to the geology of the area and sometimes not, and it remained warm. Hominid presence in the region would have first been found with Homo erectus, later with Neanderthals, and even later with Homo sapiens. By the time our story begins, the opening of the Younger Dryas 12,900 years ago, sapiens had long become the victor and the master of the world’s continents. The Younger Dryas from 12,900 to 11,700 years ago was the last great glaciation of the Pleistocene, a return to colder global temperatures that had otherwise seemed to be thawing. The Near East was not a glaciated region of the world but climate change brought precipitation differences and over the course of the Younger Dryas, the Konya Basin fluctuated between wetter and dryer.

To the south in what is now Syria, archaeological evidence shows evidence of a changing human diet in the Younger Dryas. The site of Tell Abu Hureyra has gained a distinction in recent years as possibly bearing the oldest evidence of agriculture in the world from this time, between 13,100 and 12,000 years ago. This region became colder and dryer during the Younger Dryas and the Mediterranean forest that had previously covered much of the land struggled and became reduced, making rarer the large-seeded food plants that local people could gather from the wild. The result was a change in diet as evidenced by botanical remains at the site, which shows an increase in the prevalence of wild grains. There are two possible interpretations of this. One is the more common and arguably more exciting one, that local people had begun the cultivation of grains for consumption, starting the process that would lead down the line to domestication and the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution. The other is that this was something of a false start and that a stressed population was simply making use of new resources and collected grains were increasing due to their relative availability more so than that they were being cultivated. If the former is true, it means that the cultivation of grains in the Near East actually began centuries before Göbekli Tepe was built. If the latter is true, it still tells us interesting things about the adaptability of food economies at the end of the Pleistocene, not long before the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution took off.

Karahan Tepe, photographed by Mahmut Bozarslan.

Change was coming and not far to the north back in the Konya Basin, the archaeological record would soon produce the earliest excavated examples of villages, something that would become increasingly important. The period between about 12,000 years ago and 10,800 years ago (that’s around 10,000 to 8,800 BC) is considered by Near East archaeologists to be the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A, the first temporal-cultural subdivision of the Neolithic, characterized by the first hints at growing settlements and some cultivation of plants, all predating the existence of pottery, which would be a development from around 9,000 years ago (or 7,000 BC) onwards. Aside from our main topic of Göbekli Tepe, perhaps the most notable site in illustrating the transitional world of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A in the Konya Basin is Karahan Tepe. Dating from 13,000 to 11,000 years ago (11,000 to 9,000 BC), Karahan Tepe is characterized by a vast assemblage of material culture, including many small stone and flint tools. But most striking is the stone architecture: t-shaped pillars made of huge raised and shaped stones, erected in rows and each standing about 1.5 to 2 meters in height, generally situated in carved out pool-like depressions from the bedrock that may have represented some sort of floor. The stones were clearly hewn from local rock and one massive one considerably larger than any of those standing was even found in the place it was likely quarried, measuring 4.5 meters high if it had been stood up. Of interest are also zoomorphic carvings on pillars: including two snakes, various human shapes and parts, a bird, and a strange hybrid creature with features of a rabbit and a gazelle. Another is decorated with exquisite patterns. The stone pillars of Karahan Tepe, for whatever purpose they served, were also canvases of carved art. Here some 7,000 years before the generally acknowledged origin of civilization in Sumer, humans were experimenting with construction of stone and excelling at it. The site is not unique aside from being the earliest either: recent years have been lucrative in showing that the region is full of Pre-Pottery Neolithic A megalithic sites.

Many treatments of Göbekli Tepe with less than scientific standards of description display the site as an anomaly, a unique and sudden development that defies the gradualistic processes of cultural and technological innovation, hinting that it requires an outside source of wisdom, extraterrestrial or Atlantean, to explain its existence. But newer research such as at Karahan Tepe have rendered this view wholly unnecessary. The stone architecture of Göbekli Tepe was part of a trend of local development and a pattern in local culture. The people of the Konya Basin were innovating and yet also doing things they had already known how to do. To me, far more fascinating than Göbekli Tepe being a unique site is the fact that it was a large but typical site which reveals a small sample of a dynamic world. As we explore the site of Göbekli Tepe, let’s keep this in mind.

The Site Itself

Göbekli Tepe, in an image by Wikimedia contributor Teomancimit.

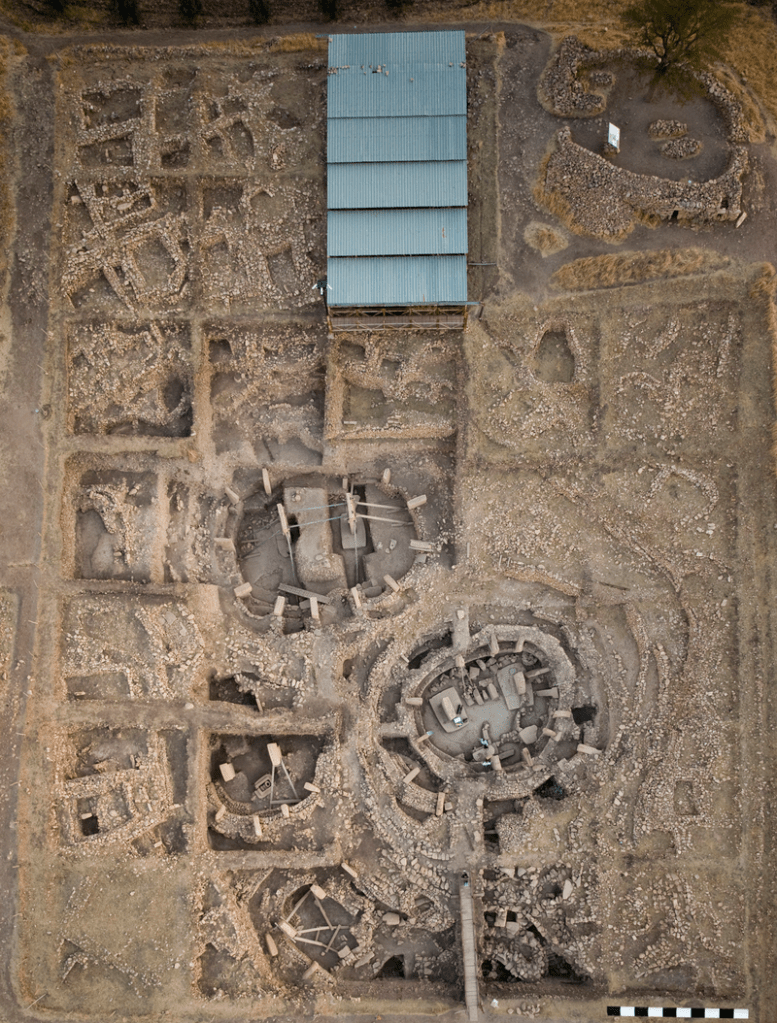

The site of Göbekli Tepe was first identified in 1963 as a tell site, a type of site common from the ancient Near East where human habitation over a long time has led to a build-up of sediment and a sort of hill over the site. The site was recognized as ancient but not properly explored or identified. Starting in 1995 however, research under German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt commenced and revealed several Neolithic structures which Schmidt considered to be temples. The “sanctuaries” of Göbekli Tepe consist of pits dug into the bedrock, like at Karahan Tepe, with t-shaped pillars organized circularly around the open space. Six of these exist in total, with some variation in size and state of preservation. Stone walls connect the outermost circle of pillars on the structures, creating a very defined interior space. Online, in both academic and popular treatments of the site, it has often been described with this “temple” moniker, often as “the world’s oldest temple.” I am wary of over-committing to that label here because the nature of any spiritual understanding of the site is, like in all discussions of prehistoric religion, incredibly difficult to assess beyond physical remains and if we do consider it a temple, we likely have to consider similar megalithic sites of the region’s Neolithic and, as mentioned earlier, Göbekli Tepe cannot continue to be considered the oldest of what it is. Some scholars have pointed out that there is a larger trend of identifying Neolithic constructed spaces with unclear purposes as temples along stereotypical lines from the perspective of our own cultural centrism. The careful study of human prehistory demands that we weigh carefully what we have evidence for and what we are assuming into our blind spots, the latter of which is different from strong knowledge.

The Göbekli Tepe excavation area from above with several of the pillared “sanctuaries” visible. Towards the top and left, other architectural remains can be seen, which have helped to inform the modern scholarly interpretation that the site was a village.

For most visitors and commentators on the site, the most defining feature is the megalithic stones so our exploration of the site should perhaps start with those. Each “sanctuary” generally has two major central pillars and a surrounding ring of them which are integrated with the walls of the pit. Considerably more so than at similar sites, the pillars at Göbekli Tepe are decorated with carvings, mostly of animals, especially predators who are often quite visibly anatomically male. Wild cats and foxes snarl and leap while boars and ducks abound as well. Interpretations vary wildly for this art. In the popular arena, the interpretation that the animals represent a zodiac is often stated as fact but this is essentially a baseless assumption, as they comprise no composite star map and there is not a strong reason to imagine any familiar zodiacal system to the one we are familiar with extends this far back into prehistory, especially as many close stars would be in slightly different positions in the night sky in accordance with stellar movements through the galactic neighborhood over a period of 11,700 years. Another interpretation which is more popular among scholars but similarly hard to test is that Göbekli Tepe was understood as a model of the sacred landscape and that the depicted animals scurried among the pillars in the flickering firelight just as their real-life counterparts scurried among the nearby hills of the Konya Basin.

An example of an animal depiction at the site, some sort of cat hunting a boar, shared on Wikimedia by user Dosseman.

An added facet to the discussion is that the t-shaped pillars seem to display some amount of anthropomorphism, their upper shape forming the appearance of arms, just as on the t-shaped bodies of humanoid figurines in later Near-Eastern art and in one of the enclosures they are decorated with belts and loincloths. There is a structural similarity here with a contemporary local art tradition exhibited in, for instance, the Urfa Man, a 1.8-meter-tall humanoid limestone statue found a mere 10 kilometers away and dating to around 9,000 BC or 11,000 years ago. The shape of Urfa Man’s body and shoulders have a lot in common with the Göbekli Tepe pillars although he has a complete set of arms that are grabbing his exposed genitals and he has a stone head.

Urfa Man, as photographed in the museum by Wikimedia contributor Cobija.

Klaus Schmidt, in keeping with common good archaeological practice, initially only excavated a small portion of the site so as to preserve some of it to be analyzed in a future where better methods of study are available. This has the side effect of meaning that a lot of mysteries about the site remain but it should be noted that continuing excavations have overturned some initial interpretations that have been oft-repeated. When I first learned about Göbekli Tepe while studying for my undergraduate degree in archaeology in the late 2010s, it was emphasized how the site did not have evidence of permanent habitation and so must have been built by non-permanent residents at this early phase in approaching true sedentism. This view has been overturned and Göbekli Tepe is in fact a village. Abutting the more monumental “sanctuaries,” there are the outlines of smaller buildings, some of which take an almost recognizably rectangular shape, which likely included residences. Here, 11,700 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene, there was a functioning town.

However, sedentists and agriculturalists are not necessarily the same thing. Much has been made of the fact that studies of food remains at Göbekli Tepe seem to show no evidence of domesticated plants or animals. And indeed, this continues to hold true. The assemblage of animal remains reflects the dietary diversity generally found among hunters, who tend to rely on the vast array of animals available and take of them opportunistically unlike pastoralists who raise a small set of animals they use intensively. By far the most prominent animal is the gazelle, which is joined also by various other ungulates including wild cattle, the Asiatic wild ass, wild boar, and red deer, with the Cape hare also being prominent. Birds show up less frequently than mammals but are also characterized by variety, but by far the most prominent is the crow. Migratory cranes also indicate seasonal hunting activity, since they would only be present at certain times of year. Tools associated with grinding grain such as slabs, mortars, and pestles as well as microscopic evidence of phytoliths are suggestive of wild grains being a significant part of the dietary makeup of local people as well, though a lack of storage facilities indicates that this was probably for immediate use rather than as a long-term economic focal point. The location of grinding tools relative to specific rectangular buildings has led to suggestions that these were economically specialized in grain-processing. Domestication definitionally brings about physical and genetic changes from wild ancestors and can be triangulated in time using both the material record and the molecular clock on existing genomes. The Göbekli Tepe botanical record seems to evidence a model in which increasingly sedentary people were harvesting wild grains nearby to them prior to carrying out domestication. It has been proposed as evidence that sedentism led to domestication rather than the other way around. This would make the inhabitants sedentary hunter-gatherers.

In the past, objections were made to the idea that hunter-gatherers could have significant social complexity, as regards both complex social complexities and inequalities as well as the capacity to build large-scale organized monuments, which is often treated as symptomatic of centralized authority. Within anthropology, the regional subfield that really destroyed this notion was that of North America, where for instance the complex, highly populous, and hierarchical societies of the Pacific Northwest coast practiced a largely hunter-gatherer-fisher economy until very recent history. By the time of European arrival, agriculture was widespread in Eastern North America, but even in non-agricultural societies such as among the Calusa of the southwestern part of Florida, monumental constructions such as burial mounds took place, indicating that only a few hundred years ago, hunter-gatherer-fishers were organizing large-scale monumental works in the Everglades. Another development that has occurred in the theory of hunter-gatherer studies is the recognition that not all cultural changes in these societies need to be explained by purely environmental factors, as older researchers were sometimes inclined to do, but rather in light of cultural autonomy and innovation. Cycling back to the Near East and taking this into consideration, we do not need to treat Göbekli Tepe’s apparent economic diversification and monumentality as precluding it being a hunter-gatherer site. The evidence points to it falling into this category of “complex hunter-gatherers” and perhaps in the long slow process of the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution, it is no surprise that this is one of the phases that occurred.

A final fascinating detail about Göbekli Tepe is that it was apparently intentionally buried quite rapidly (in archaeological timescales). Rather than being left to the elements, the various “sanctuaries” were filled in with soil and small stones, which has aided their preservation greatly. We obviously have no idea why this was done and the easy answer is a ritualistic practice of some sort. Some have suggested that the burials were not contemporaneous but rather the several “sanctuaries” represent a sequence of used structures that were retired before another was built, the periodic fillings creating the sort of dirt hill they are built into. Whatever the case, around 8,000 BC or 10,000 years ago, the site fell out of use and faded into the archaeological record to be found on the other end of the Holocene and be wondered about by our generation. In its abandonment, the Neolithic continued for millennia.

The Legacy of the Town

In the grand scheme of history, Göbekli Tepe was probably not very important. It existed as a part of a dynamic world that we find through disparate samples and it is the largest sample of this place and time that we have. But this fact makes it hugely important to us in seeing the trend it was a part of. It is one more strong data point to show that village life probably came before agriculture and not the other way around as sometimes assumed in the past. It also provides an example, albeit not a lone one, of monumentality being expressed as early as the end of the Pleistocene. As I’ve emphasized here, Göbekli Tepe can now be said to exist in a context and while our data points are still not much, we can start to build the world it existed in as an arena in time and space. And in the wake of this world followed a series of others.

Remains of the wall tower of Jericho from around 8,000 BC in the modern West Bank. This image is by Wikimedia contributor Salamandra123.

As I mentioned before, a contemporary site in modern Syria at Tell Abu Hureyra was potentially experimenting with grain cultivation at an early date. This site’s material is assigned to the Natufian culture, which flourished in the Levant between about 15,000 and 11,500 years ago (that’s 13,000 to 9,500 BC). In the wake of the Natufians, an increasingly localized array of material cultures began popping up with their own innovations on agricultural settlement. Perhaps the most famous of these is Jericho, located in what is today the West Bank adjacent to a modern Palestinian city of the same name. From around 10,000 BC (12,000 years ago) onward, Jericho was a Natufian hunter-gatherer site but after 9,500 BC (11,500 years ago), the site became an agricultural settlement and one of the most long-lived in history at that. As cereal grains proliferated as a domesticated food source throughout the world of the ancient Levant, the cohesion of farming settlements became more pronounced. Around 8,000 BC (10,000 years ago), Jericho became the oldest site we know of to erect a settlement wall, as well as a small tower. The wall was rather short and perhaps it was less to use against outside invaders and more to defend against the flash floods that remain problems in times of significant rains in much of the West Bank. With some short interruptions, Jericho would remain inhabited into the historic period, peaking in size in the Early Bronze Age around 2600 BC and later being one of many sites to be destroyed and abandoned in the Late Bronze Age collapse of around 1150 BC. It was likely the ruins of this phase of the settlement that were remembered when the earliest segments of the biblical Book of Joshua were written in the late 600s BC, by which time the site had been resettled as part of the Kingdom of Judah. The Jericho narrative in this book features city walls quite prominently, a Near-Eastern legacy that began in this area millennia before.

Çatalhöyük, an archaeological site in southern Turkey dating to between 7,100 and 5,700 BC, in a photo by Wikimedia contributor Murat Özsoy 1958.

Another site which when juxtaposed with the likes of Jericho emphasizes the variety of settlements in the Neolithic Near East is Çatalhöyük, located in the southern part of modern Turkey, 700 kilometers west of where Göbekli Tepe is. This site was a densely packed town inhabited between around 7,100 and 5,700 BC (or 9,100 to 7,700 years ago), which seems to have peaked with a few thousand inhabitants, feeding them off a thriving economy of domesticated grain and with animal pens built on the roofs of buildings. Actually the roofs comprise the public space of the town; no streets exist to separate the various buildings, which are relatively undifferentiated. Houses would have had an entry in the roof and probably helped to keep each other warm by being close together. Despite its size, gargantuan for the Neolithic, it lacks the differentiated building purposes of later cities with cultic activities seemingly happening in domestic spaces. Clearly the large-scale construction and management of a large population is indicative of a highly organized society but the palaces and monumental spaces we associate with political hierarchy are not readily apparent. The different ways these communities organized themselves, addressed problems, and managed their built environment is a reminder that the Neolithic was neither a progression or an event, but a very long and diverse process of experimentation as dynamic as any history afterwards, just perhaps a little less visible to us beyond what evidences we’ve found.

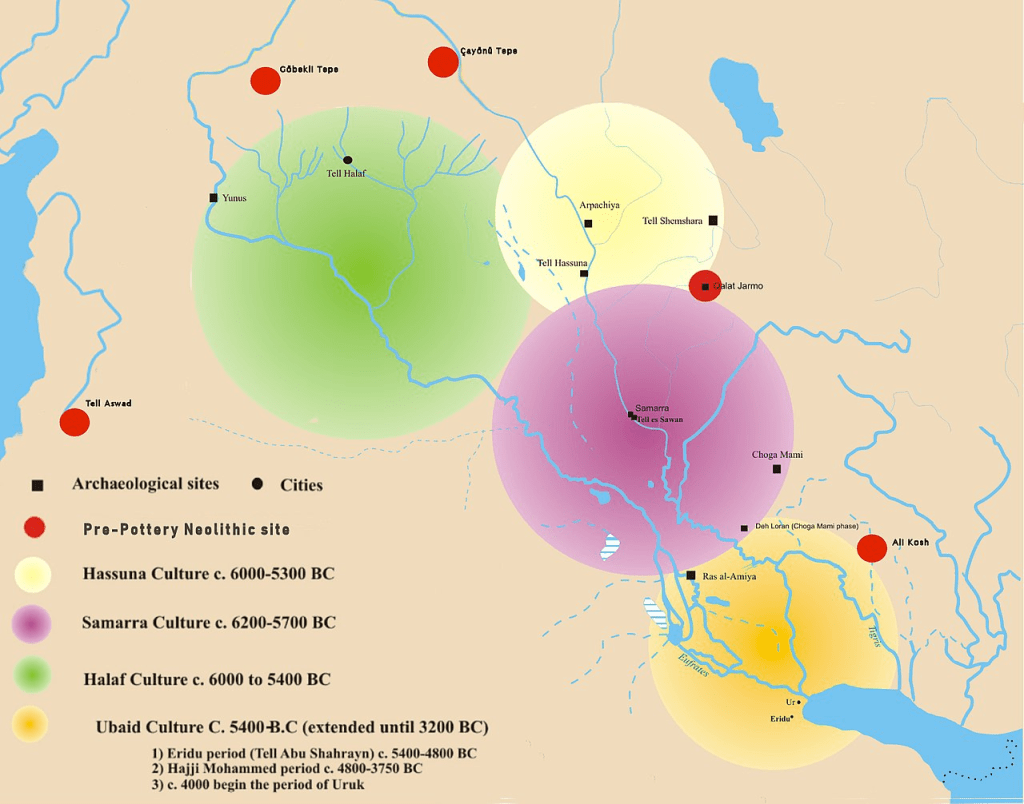

A map of some of the late Neolithic material cultures of Mesopotamia, by Wikimedia contributor Jolle.

Of course in retrospect, it is easy to see which geographical extension of the Near-Eastern Neolithic led, in a quite literal sense, to the history that followed. The geographical region of Mesopotamia starts in the east of modern Syria and runs southeast through the extent of modern Iraq to the Persian Gulf, defined by the alluvial plain around the Tigris River to the north and the Euphrates River to the south. This fertile wonderland very naturally became productive for farming economies and for the feeding of large populations and in the later part of the Neolithic, it was host to an array of agricultural cultures. Two of particular note are the Halaf culture of Upper Mesopotamia (around 6,100 to 5,100 BC) and the Ubaid culture, centered initially in Lower Mesopotamia but later heavily influencing the north as well (around 5,500 to 3700 BC). Settlements peppered the landscape and populations grew but perhaps the most dramatic development was the long-distance movements of goods between trading centers. Studies of obsidian in Halaf and Ubaid sites has found connections deep into Anatolia and the Caucasus while cultural influences spread the length of the Mesopotamian plain, Ubaid pottery types coming to define almost the whole region by the end of the Neolithic. The groundwork was laid and with the start of the Uruk period (around 4000-3100 BC), what is generally seen as civilization began as the Sumerians constructed vast cities with enormous central temples and ruling institutions, significant economic specialization, and the written word. The rest is, in the traditional limitations of the word, history.

In the last few decades of archaeology, few sites have been as impactful to how archaeologists have modeled our understanding of the human story as Göbekli Tepe. But to fully appreciate what the site means, we have to look at both what the site consists of and its context, both the emergent dynamic perspective we have of its contemporary region and its larger place in the story of the Neolithic transition. It is a story of local innovators, of branching and diverse experiences, and of sedentism perhaps leading to agriculture. Who knows what details will be added to this amazing story in a few more decades?

Further Academic Reading

- Banning, E. B. “So Fair a House: Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East.” Current Anthropology 52(5), 2011: 619-660. 661207 (uchicago.edu)

- Bar-Yosef, O. “The Walls of Jericho: An Alternative Interpretation.” Current Anthropology 27(2), 1986: 157-162. The Walls of Jericho: An Alternative Interpretation (harvard.edu)

- Bressy, C.; Poupeau, G.; and Yener, K.A. “Cultural interactions during the Ubaid and Halaf periods: Tell Kurdu (Amuq Valley, Turkey) obsidian sourcing.” Journal of Archaeological Science 32, 2005: 1560-1565. https://www.academia.edu/download/14470477/bressiobsidian.pdf

- Briar, Clinton. “Carving Space from Place: Possible Phenomenological Scenarios at Göbekli Tepe.” 2020. https://www.academia.edu/download/65978158/Clinton_Briar_Carving_Space_from_Place.pdf

- Çelik, Bahattin. “Karahan Tepe: a new cultural centre in the Urfa area in Turkey.” Documenta Praehistorica XXXVIII, 2011: 241-253. https://journals.uni-lj.si/DocumentaPraehistorica/article/download/38.19/1651

- College, Sue and Conolly, James. “Reassessing the evidence for the cultivation of wild crops during the Younger Dryas at Tell Abu Hureyra, Syria.” Environmental Archaeology 15(2), 2010: 124-138. https://www.academia.edu/download/38461006/2010_Colledge_Conolly_Reassessing_the_evidence_for_the_cultivation_of_wild_crops_during_the_Younger_Dryas.pdf

- Coombs, Alistair. “Hearing the Dead: Supernatural Presence in the World of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) in Reference to the Balikligöl Statue.” Paranthropology 7(1), 2016: 42-45. https://www.academia.edu/download/47220752/Paranthropology_Vol_7_No_1.pdf#page=42

- Dietrich, Laura et al. “Cereal processing at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey.” PLoS One 14(5), 2019. Cereal processing at Early Neolithic G#_#x00F6;bekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey (plos.org)

- Hodder, Ian and Cessford, Craig. “Daily Practice and Social Memory at Çatalhöyük.” American Antiquity 69(1), 2004: 17-40. https://www.academia.edu/download/30523912/practice-memory-catalhoyuk.pdf

- Hublin, Jean-Jacques et al. “New fossils from Jebel Irhoud (Morocco) and the Pan-African origin of Homo sapiens.” Nature, 546 (7657): 289-292. Submission_288356_1_art_file_2637492_j96j1b.pdf (kent.ac.uk)

- Kaplan, Matt. “Million-year-old ash hints at origins of cooking.” Nature 2012. Million-year-old ash hints at origins of cooking | Nature

- Kuzucuoğlu, Catherine et al. “Reconstruction of climatic changes during the Late Pleistocene, based on sediment records from the Konya Basin (Central Anatolia, Turkey).” Geological Journal 34, 1999: 175-198. 010020562.pdf (ird.fr)

- Sassaman, Kenneth E. “Complex Hunter-Gatherers in Evolution and History: A North American Perspective.” Journal of Archaeological Research 12(3), 2004: 227-280. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kenneth-Sassaman/publication/225916989_Complex_Hunter-Gatherers_in_Evolution_and_History_A_North_American_Perspective/links/5654440a08aeafc2aabbb0c0/Complex-Hunter-Gatherers-in-Evolution-and-History-A-North-American-Perspective.pdf?origin=journalDetail&_tp=eyJwYWdlIjoiam91cm5hbERldGFpbCJ9

- Schmidt, Klaus. “Göbekli Tepe.” The Neolithic in Turkey: New Excavations and New Research: The Euphrates Basin, 2, 2011: 41-83. https://www.academia.edu/download/61530312/A115NeolinTurkeyk20191216-81466-knsw77.pdf

Living in the Longue Durée is part of the History Nerds Network, a group of friends who together make history content online. Check out our Discord server here if you’d like to chat with us: https://discord.gg/dzdrzUpKeG You can also follow for post updates on the Facebook page ( https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61559902349797 ) or on Instagram at @livinginthelongueduree .

Consider supporting my time and money investment into research on Patreon if you want to allow articles like this to maintain their quality and regularity: Living in the Longue Durée | A thoughtful and eclectic history blog. | Patreon

Leave a reply to Nigeria wildlife Cancel reply