This place is a message… and part of a system of messages… pay attention to it!

Sending this message was important to us. We considered ourselves to be a powerful culture.

This place is not a place of honor… no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here… nothing valued is here.

What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us. This message is a warning about danger.

The danger is in a particular location… it increases towards a center… the center of the danger is here… of a particular size and shape, and below us.

The danger is still present, in your time, as it was in ours.

The danger is to the body, and it can kill.

The form of the danger is an emanation of energy.

The danger is unleashed only if you substantially disturb this place physically. This place is best shunned and left uninhabited.

–Sample message from the 1993 Sandia Report, proposed to be placed in New Mexico’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant and written in English, Spanish, French, Russian, Arabic, Mandarin, and Navajo.

Talking Across Time

When I went to high school, one of the activities that the school had us do was to write a letter to our future selves. Freshman Jacob wrote a letter to senior Jacob so that when the four years passed, he could open it and learn something about the time that had passed. It is fascinating to receive a letter from yourself and look at the subtle or dramatic change in views on things, on place in life, on achievements. I write a lot, often just for myself, and from time to time it is fascinating to uncover a heartfelt note I had forgotten to myself, anticipating myself reading it again someday, with sometimes great awareness of how things would be and sometimes a lot of retrospective naïveté. But what if instead of across four years, I wrote something at a distance of forty, a distance as far into the future as we are now from the 1980s? How would I address myself across half a lifetime and how would it impact me differently? What would later me think about what earlier me had to say? What if I were to write to people in my community in 400 years, reaching as far ahead into the future as I would reach back to the earliest English colonies in North America? Would my values and way of talking reflect severe changes in society since my time? Would the concerns I shared even be considered relatable? What if I wrote to people of whatever culture inhabited my part of the world in 4,000 years, stretching a distance forward equivalent to stepping back to the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur in Sumer or the founding of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt. Would the language I use have become undeciphered? Would civilization have advanced so far that the basic life experiences of the readers would not deeply connect with mine? And what if I wrote to an audience 40,000 years from now, as distant to me as I am from the last Neanderthals? How could I dare to even try to connect with them at this timescale, to communicate an idea across the sheer amount of history and even potentially evolution and changes in the landscape that might efface my message? What if I needed to warn that generation of something across tens of thousands of years?

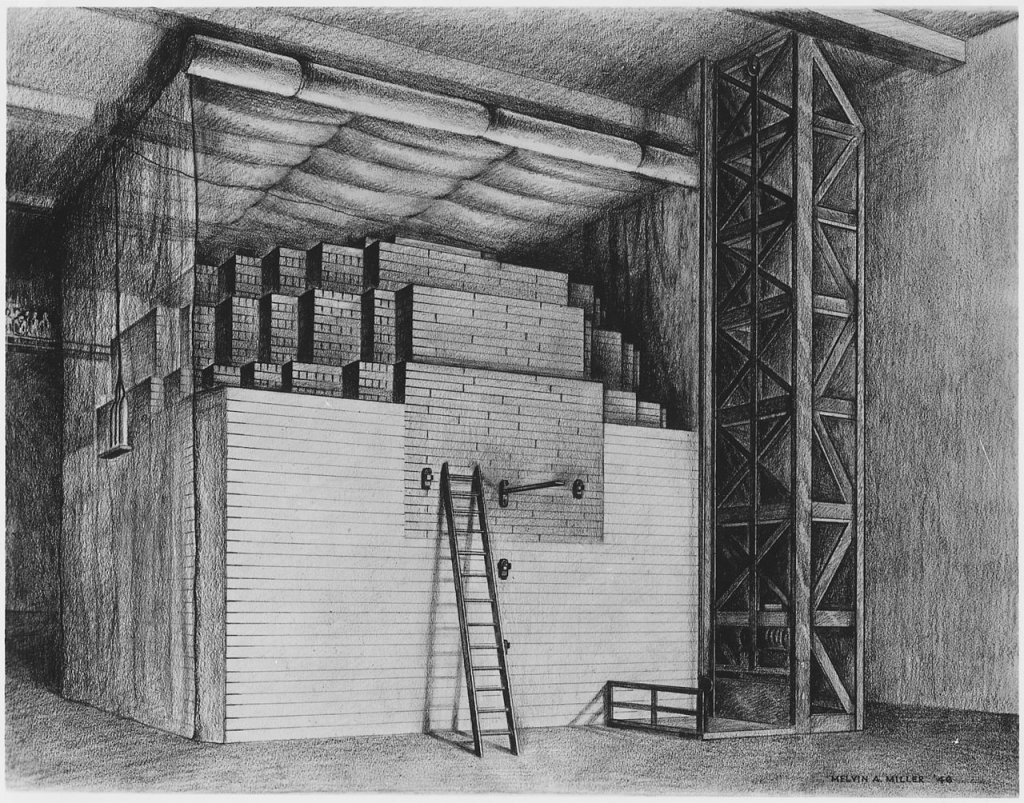

Chicago Pile-1, depicted here in a drawing from the United States Department of Energy, was the first man-made nuclear reactor, operating from 1942 to 1943 as the first successful nuclear experiment of the Manhattan Project. Scientists trusted Enrico Fermi’s calculations enough to let him pull this off in downtown Chicago.

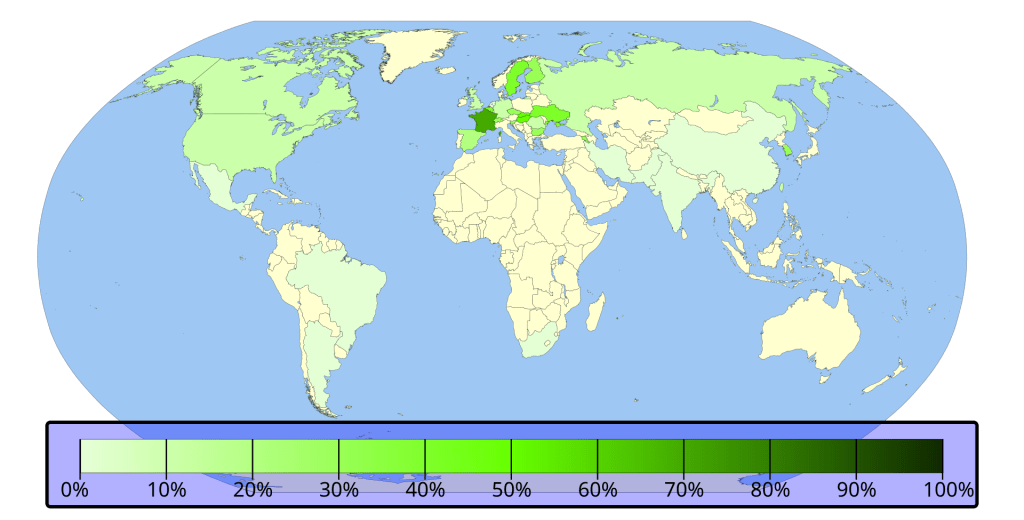

In 1942 as part of the Manhattan Project, American scientists under the direction of Enrico Fermi made an achievement that would come to impact the geological record of our age for millions of years to come. Using natural uranium as fuel, the secretly developed Chicago Pile-1 became the first machine to facilitate sustained anthropogenic nuclear reactions. The nuclear reactor was born and the scientific ideas it tested would lead to the atomic bomb three years later and a new means of generating power in the next decade. The exact number of nuclear warheads ever produced is not exactly known because various programs of state secrecy obscure exact details but a 2013 study estimated that since 1945, the total had been approximately 125,000 (the vast majority of these are no longer active, due to going unmaintained and weapons reduction measures by the two largest producers, the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia; somewhere around 12,000 nuclear warheads are armed today). More significant for our story today is nuclear power however, which as of 2024 accounts for about 10% of the global electricity grid. Nuclear power does not release greenhouse gas emissions and so is a popular option as an alternative to fossil fuels in the age of anthropogenic climate change. We truly live in the atomic age with these two technologies creating major material changes in our world as it exists today.

But an ethical dilemma stems from a simple fact of physics: the accumulated radioactive materials of the wastes of these materials are often incredibly dangerous and will remain so for significant amounts of time. There are now millions of cubic meters of nuclear waste in the world and for some of the high-level materials, estimates forecast that it will continue to be dangerous for potentially up to 100,000 years. It needs to go somewhere and when it gets there it needs to stay. For this reason, facilities exist or are in development for the storing of massive amounts of nuclear waste for an extremely long time. Typically these repositories are deep underground, safe from being ripped open from developments on the surface. And when retired, plans exist to bury the facilities and keep them safe in the ground. Most infrastructural plans assume structures need maintenance and that if they do not receive it, they will be far less permanent than tens of thousands of years. This means that long-term nuclear waste storage presents a somewhat unique challenge in that a fundamentally long-lived unmaintained structure must be constructed and somehow humans have to be made not to go in for a vast amount of time. “Longtermism” is the ethical position that we have a moral duty to future humans as well as those alive today. Within a longtermist mindset, it becomes apparent that attempting to keep distant generations of humans, no matter what history occurs between now and then, safe from the dangers we create today is a moral duty. For this reason, there is much discourse on how to communicate a message deep into the future for those who follow us to warn them of these dangers.

Normally on this blog, we explore the very distant past and its relationship to the present, through the lens of our lines of evidence which are preserved. This time, we are imagining ourselves as the past we will someday be, through the lens of one of the few industries that habitually must practice this.

Three Nuclear Waste Repositories

There are a number of nuclear-waste storage facilities opening up around the world, but most are fairly new and therefore few actually contain very much material. As such, the repositories I highlight here may undergo significant developments as this article ages, the long-term warning messages may end up looking entirely different, and it is possible that some may not open at all. Regardless, the three I want to take special interest in are the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, USA, the Onkalo in Finland, and the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository in Nevada, USA.

The above is the official introductory video for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant from its website, produced by the United States Department of Energy.

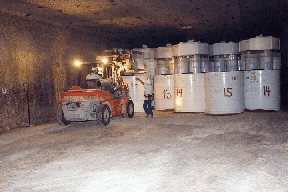

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant is the United States’s only currently operational deep geological repository for nuclear waste. Located near the very southeastern corner of the State of New Mexico, WIPP was authorized by Congress in 1979 to store transuranic waste products (that is, composed of or contaminated by elements beyond uranium, element 92, on the periodic table of the elements, which are all unstable) created in the development of nuclear weapons. The facility’s storage is 660 meters underneath the New Mexico scrubland in the middle of a colossal underground salt formation that forms part of the Delaware Basin. For context, the tallest building on Earth, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, is 828 meters in height, meaning that the distance between the surface and the nuclear waste is further than the height of almost any of the world’s skyscrapers. The facility received its first shipment of waste in 1999, which came from Los Alamos, New Mexico, where in 1945 the first atomic bomb was detonated in the Trinity test, the final triumph of the Manhattan Project before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki weeks later that ended World War II. Over the latter half of the 1900s, the waste from nuclear weapons tests had been accumulating at supposedly temporary surface facilities around the country, creating a number of accidents waiting to happen. WIPP offered a solution to this problem and for the last two decades and a half it has been taking in this waste. On February 14, 2014, a damaged storage drum in the facility exploded and released trace particles of plutonium and americium, setting off alarms as radioactive material drifted into the air outside of the storage room. 21 workers received low-level radiation poisoning. The chamber was evacuated and not entered for months due to security reasons, meaning that investigating the problem was not possible for that time until workers finally reentered in late April and found evidence of fire. It is the possibility of situations like this that makes for both the need to store nuclear waste in remote underground locations and the danger of these facilities once they become used.

Nuclear waste containers in storage at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant.

The geological setting of WIPP is very purposeful. Since it is in a cave excavated out of salt, the compacted salt is prone to slowly close under its own weight, meaning that the open storage space shrinks in height by a few centimeters a year with regular stability assessments checking up on things to ensure safety while workers are there. However, the hope is that when it is full and time to go, this same process will cause the salt to close around the waste materials and hold them there, deep below what is permeable to groundwater or easily accessible to the surface. The requirements the Department of Energy had to follow for WIPP prescribed at least 10,000 years of integrity in holding these materials and by all means the location should provide that. The surrounding geology consists of materials laid down in the Permian Period (299-252 million years ago) that have been waiting there since before the first dinosaurs even evolved. The one conceivable threat to the facility is future humankind, which may find reason to mine some of the natural wealth of the ground, such as the region’s salt and oil deposits, both currently harvested in nearby parts of New Mexico and Texas. The chances of hitting the installation by chance at the depth it sits at is probably quite low, but by the nature of history in the longue durée, impossible to be sure of.

Map of countries color-coded by the percentage of their electricity grid which is produced by nuclear power as of 2023 data. Only two countries, France (64.8%) and Slovakia (61.3%), produce more than 50% of their electricity grid by nuclear power. Due to the expensive infrastructural limitations, nuclear power is an inaccessible luxury to most of the world’s least developed countries. Graphic by Wikimedia user NuclearVacuum with data from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

While the US has been pushing forward at storing nuclear waste from weapons programs, headway in storing the vastly higher amounts that come with nuclear energy has been moving forward in recent years in Europe. In raw production, the United States is the largest producer of nuclear energy by a vast margin at 779.19 TWh, but this is also due to the US being the world’s largest economy and having a colossal power grid, nuclear only accounting for 18.6% of the national energy source (putting it in 17th by this measure). Many European countries are far more reliant on nuclear power as a share of their total energy budgets however, most notably France for which nuclear provides for 64.8% of the energy grid (and at 323.77 TWh, France produces the third highest national total of nuclear energy). Wildly, neither the United States nor France has a currently operating long-term mass-storage facility for non-weapons nuclear waste, though both have plans in development, meaning that the waste they produce in vast amounts is sitting in supposedly temporary storage, which may or may not be particularly secure. A much smaller national economy, that of Finland, is instead paving the way for what may be the future of European nuclear fuel storage. At 32.76 TWh accounting for 42% of the energy grid, Finland is 12th in total nuclear power production, but fourth in the portion of the national energy grid nuclear accounts for. As of writing this post, sometime in the next few years the Finnish government will formally open its first long-term nuclear waste storage facility with differences in some details from its American weapons-materials counterpart WIPP.

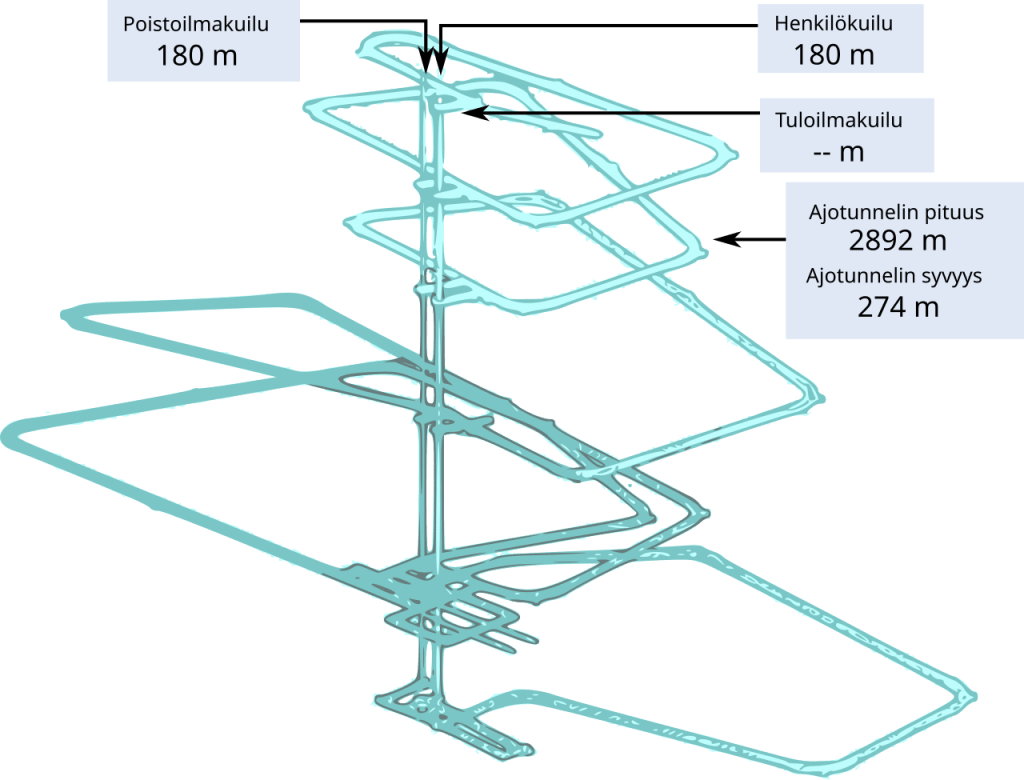

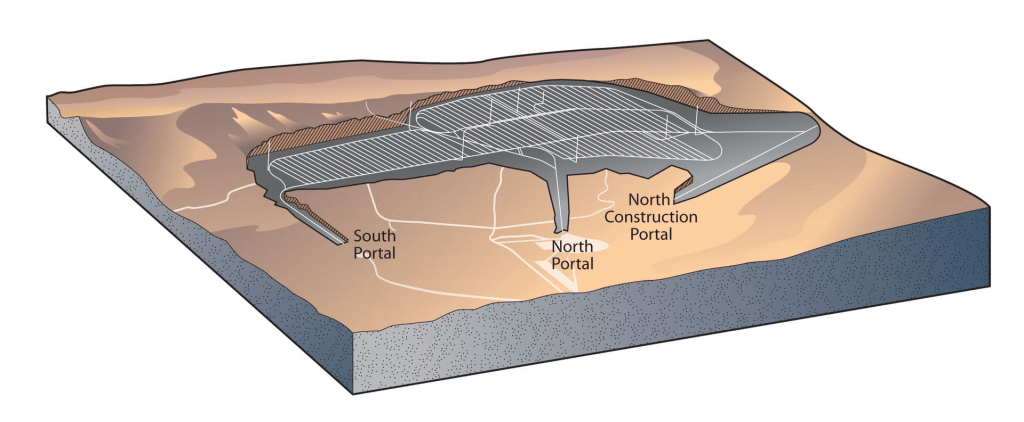

A schematic from a 2007 Finnish government report detailing the shape of the tunnels that will make up the Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository.

Olkiluoto is a small island off the southwest coast of Finland in the Baltic Sea which houses one of Finland’s two nuclear power plants, run by the company TVO and operational since 1979. The island was also designated in 2000 to play host to the nation’s repository for spent nuclear fuel, which became known as Onkalo, humbly meaning “small cave.” Construction began in 2004 and the project proved to be anything but small, involving both of Finland’s licensed nuclear power companies working together along with the government to build a facility designed for 100,000 years of security. The storage locations are distributed between 420 and 520 meters below the surface and fuel is to be interred according to the Swedish-developed KBS-3 method of storage, which is used as a prospective model across Scandinavia. The methodology involves taking spent waste and storing it in copper canisters which measure five meters long and have exteriors five centimeters thick, weighing around 25 metric tons when filled. The canisters are then inserted into the bedrock and surrounded with bentonite clay. This system creates a leak-proof non-corrosive container for the waste while also protecting it from long-term geological changes and pressures. Compared to their American counterparts, Scandinavian solutions project security about ten times longer, whatever that means at the incredibly long timescales these engineers imagine across. 100,000 years of durability is a completely new challenge in the history of human achievement.

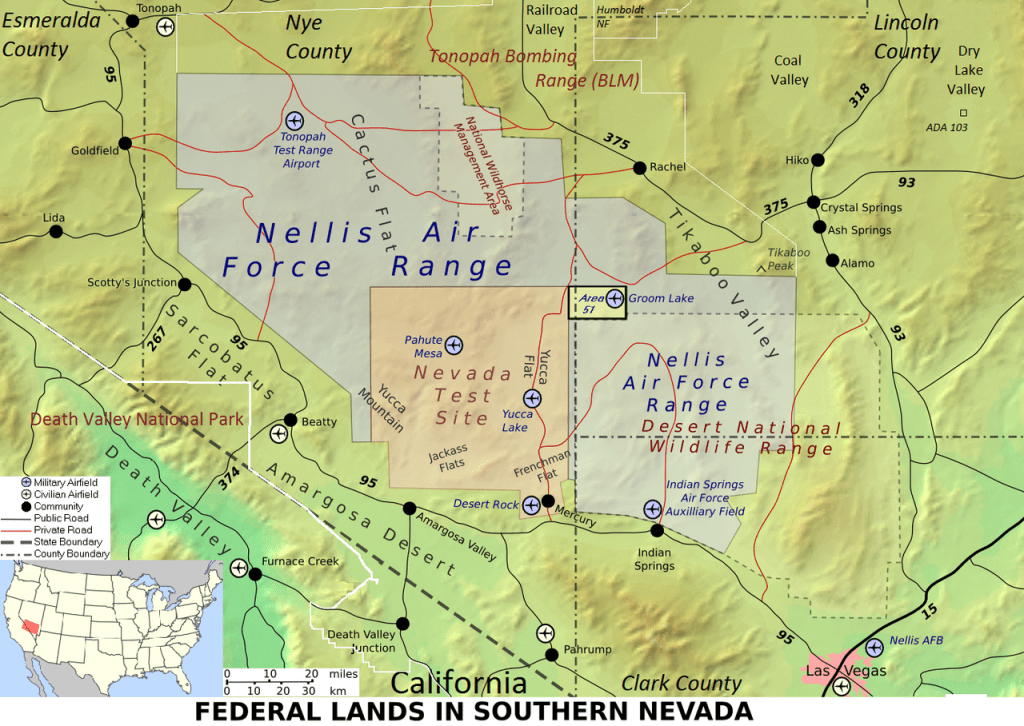

A map of federal-owned lands in southern Nevada, provided by Wikimedia user Finlay McWalter. Yucca Mountain is located on the western edge of the Nevada Test Site, where the United States tested nuclear bombs from 1951 to 1992.

If in thousands of years archaeologists excavate the ancient civilization that we today call the United States of America, perhaps one of its strangest regions to study will be what is now southern Nevada. In the very south is Las Vegas, itself a rather unique American city for reasons that go without saying and some distance north of it is City, one of the largest sculptures ever built, in the middle of the remote desert approximating an empty sloping city of stone and concrete 800 meters by 2,400 meters in size. If you go partway between these two strange monuments to the abstract thought of humankind and go west, you will find yourself on one of the largest patchworks of federal land in the United States. The most famous part of this is the infamous Area 51, of which I’m sure the long-term archaeological implications are difficult to say as an uninformed member of the general public. West of this is a vast region of desert known as the Nevada Test Site where between 1951 and 1992 the United States detonated 928 nuclear bombs (100 of which were above ground until the US stopped doing this following the Limited Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union in 1963, after which the US conducted 828 further subterranean tests at the site). The site even included army training exercises for ground maneuvers in the wake of an atomic strike, which is utterly wild to imagine now after the Cold War, and neighboring Las Vegas had to deal with periodic light tremors and heightened cancer rates. The Nevada Test Site is still undergoing cleanup today of the incredible amounts of hazardous materials peppered throughout the desert. Aside from stored nuclear waste, our period of civilization has certainly already become the first to mark our future stratum in the geological record with artificial massive bursts of radiation from all the nukes detonated over more than half a century. Southern Nevada will bear that chemically detectable mark for millions of years.

Plans for the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository from the United States Department of Energy.

It is into this bizarre part of the world that the United States Department of Energy has proposed finally storing the USA’s used nuclear fuel for the long term. Yucca Mountain is located on the western part of the Nevada Test Site on government land. As early as 1987, it was scouted as a location to start putting high-level nuclear waste by the DOE and in 2002 the US Congress formally approved the project to hollow out a large portion of the mountain for a repository. When completed, it would comprise the largest storage of nuclear waste in the world, projections allowing for 77,000 metric tons of material stored inside (as of 2021, the US had 70,000 metric tons of this material needing to be stored, increasing by 2,000 a year, meaning that even if the repository is constructed the US will be in need of another similar facility soon). While for many Americans this safe storage is seen as sorely needed, for those in the area itself the idea of tens of thousands of tons of deadly material taking up residence for thousands of years in the region is deeply uncomfortable. The State of Nevada fought to prevent the federal government from completing this project, citing concerns about the safety regarding geology (Yucca Mountain was formed by volcanic activity but what the state government’s website does not mention is that it has not erupted in 80,000 years), water drainage polluting local aquifers, the potential for deadly accidents in the transportation process of nuclear waste from around the country to the site, and even the idea that the site might be a ripe target for terrorists. All of this is still on the official website of the state’s attorney general. Additional opposition comes from the local indigenous Shoshone nation, which has long had problems with the United States government carrying out nuclear activities on its ancestral land and which has historical sacred value placed on Yucca Mountain where important religious ceremonies have taken place for centuries. In 2011, Congress responded and ceased federal funding, effectively halting the ongoing construction, which remains unfinished. Despite repeated cries that something needs to be done about the USA’s growing piles of unstored high-level nuclear fuel waste, the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations have all neither encouraged new funding of the Yucca Mountain project nor put effort into designating another location.

As I hope I have demonstrated in the above segment, there is a lot of nuclear waste in the world and it is increasing every day. Working concepts such as WIPP and soon-to-open Onkalo show that long-term safe storage is technologically feasible in theory while others such as Yucca Mountain show that societal factors make solutions to this problem at scale in the present difficult. In thousands of years, when whatever future version of our species’s society opens up the places we have left our long-term waste, how we store it will affect their experiences of it, their safety, their very ways of knowing about us. The atomic age is not just a political period of human history but a geological event in the material record below our feet that is still forming. Now we turn to how long-term thinkers deal with that and the conversation we must have with our descendants.

Putting Signals into Deep Time

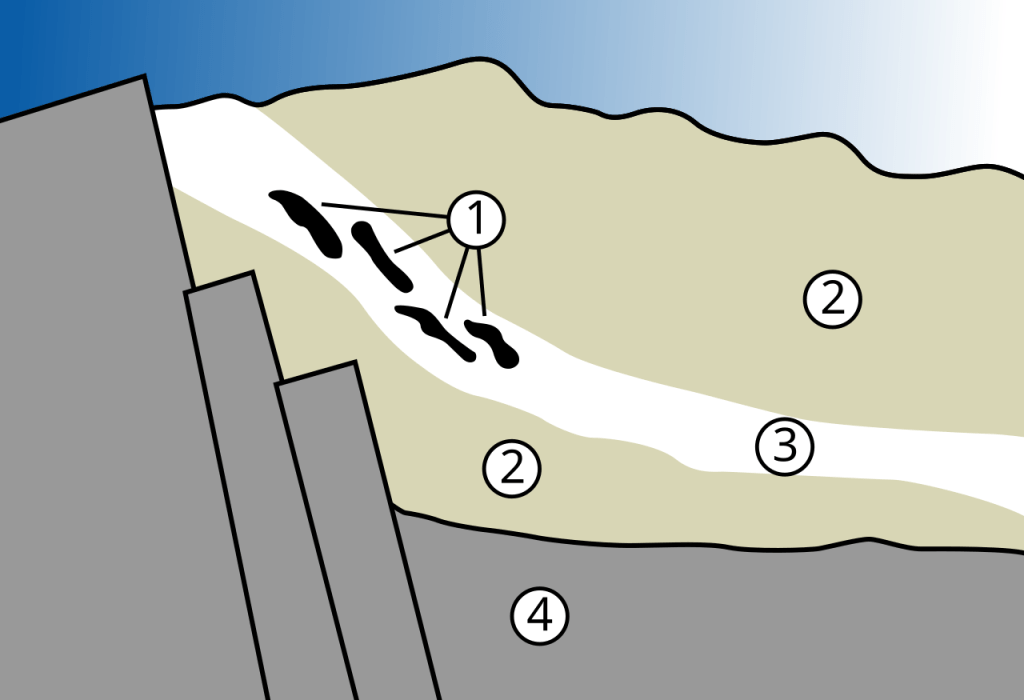

Diagram from Wikimedia contributor MesserWoland showing the geological structure that allowed for the Oklo natural nuclear reactor to function. 1 is cavities that functioned as reaction chambers, 2 is the sandstone surroundings, 3 is the uranium ore layer, and 4 is granite bedrock.

For starters, before we even apply semiotic or written labels, how long will evidence of nuclear reactions be detectable in the material record? As a case study, the oldest example we have to study reactor material in geology is 1.7 billion years old. No, really. In 1972 at Oklo in Gabon where uranium was mined and then used by foreign countries such as France (from which Gabon had gained independence 12 years earlier), French researchers noticed strange things going on with the proportions of isotopes in the local uranium. Normally, 235U (that is, uranium-235, which has 92 protons per atom as all uranium definitionally does and 143 neutrons; the two numbers add up to 235) is the most common fissile isotope of uranium, making up .72% of given natural samples (meanwhile non-fissile 238U makes up around 99% of natural uranium). At Oklo, however, 235U only accounted for around .44% of uranium samples. For security reasons, this required investigation, as depleted fissile material might indicate that in the production line it was being siphoned off from the energy sector for use in nuclear weapons. Rather than a Gabonese nuclear-weapons program, the investigation discovered something far more geologically interesting: nuclear decay products such as neodymium and ruthenium that indicated that sustained nuclear fission had been occurring within the ground. The Oklo region had natural nuclear reactors.

1.7 billion years ago, the Earth was in the Statherian Period of the Paleoproterozoic Era and was characterized by single-celled microbial life in the seas while the lands sat barren under an atmosphere that had been gifted oxygen by photosynthetic cyanobacteria but which was still far below the levels we have today, giving the sky a somewhat Mars-like orange hue. The continents were almost all gathered together into the supercontinent Columbia and the first eukaryotic organisms were only 100 million years away. Meanwhile the uranium deposits of Oklo were already locked in the ground. As this was a significant fraction of the history of the Earth ago, less of the radioactive materials seeded from space in deep prehistory had decayed and it’s believed that natural uranium consisted of about 3.1% 235U, close to the concentration in refined material in modern nuclear reactors. As groundwater seeped into cavities in the ore, the water acted as a medium for the movement of neutrons emitted in decay, allowing for chain reactions to take place. Over the course of several hours, these chain reactions would intensify and induce fission, heating the water up and boiling it out in the process. With the water gone, the process would stop and the system would cool down until groundwater filled the cavity again, repeating the cycle. In this way, specific geological details allowed for a sustained nuclear reactor to exist for some time. This seems to have happened within at least several spots in the region. Due to differences in the concentration of uranium isotopes on the planet at the time, it is unlikely that such a natural system could form itself today. I am not a nuclear scientist and in researching this I had to become familiarized with topics very much outside of my zone of expertise. For those more versed in the physics of nuclear energy, I encourage you to look at my source Petrov et al. to see calculations of the numbers associated with the Oklo reactor.

For our purposes though, the Oklo reactor provides a case study for how long the material remains of nuclear activities will be detectable for hypothetical future civilizations with technological and scientific capacities similar to us. And the answer is not tens or hundreds of thousands of years but billions. The nuclear industries of our present civilization operate at far more extreme scales and quantities than these prehistoric reaction chambers that formed by chance and by all means we are furnishing a new and relatively unique layer here in the Anthropocene which will signal our achievements in the rock record throughout whatever future history life on our planet endeavors its way through. It is perhaps also, maybe less excitingly, exactly why we can be very certain that no significant nuclear civilization on our planet has come before the last century. As we think towards our long future though, we have to measure the longevity of culture against the vastly greater longevity of nature. For the next 100,000 years, our species might be here and our waste storage will be dangerous for those of us who are. We approach the question that inspired me to write this piece in the first place: how do you write across such an immense stretch of time?

The United States was the first country this problem was addressed in and likely the one that has done the most work on it. The Human Interference Task Force was a team of experts that first convened in 1981 in cooperation with the US Department of Energy for the purposes of compiling a report to inform policy for the DoE and for construction companies that would build repositories. WIPP had just recently been approved in concept and would come into being as a whole new type of facility and Yucca Mountain would be scouted as a location later that same decade. The task force compiled a 1984 report that took many factors into account in reducing human entry into the sites. Many of these factors had to do with location. For example, a repository should be placed away from valuable natural resources that a future civilization might dig for to minimize accidental breaching. The stability of natural geology and absence of groundwater over long periods of time were also key. Messaging was to be placed both on-site and off-site so that ideally it would be discovered before the actual repositories were. This might include a message on perhaps a notable nearby geological figure like a mountain that was likely to stay intact for a long period of time but also be extremely visible. Stone has incredible staying power after all and many models have predicted that if humans were to go extinct in the near future, our massive stone structures such as the Great Pyramid of Giza and Mount Rushmore might be some of the last on the landscape. In general, monolithic (that is, made of a single massive stone) designs could be expected to be more durable than ones made of multiple fitted stones. Malicious activity by humans was also a concern as vandalism by one future generation might damage the message for those further down the line. Aside from specifically constructed warnings in place, ensuring the site is recorded in the historical record that can be passed down may allow knowledge of it to be transmitted and translated across cultural changes, though of course historical records themselves can easily be cut short when one generation simply does not see the need to copy and propagate specific old information longer. And seeing as there are currently no historical records from more than 5,000 years ago (and any script close to that had to be deciphered again after being unreadable for thousands of years), there is not good precedent to conclude that the historical record would carry specific information for up to 10,000 years.

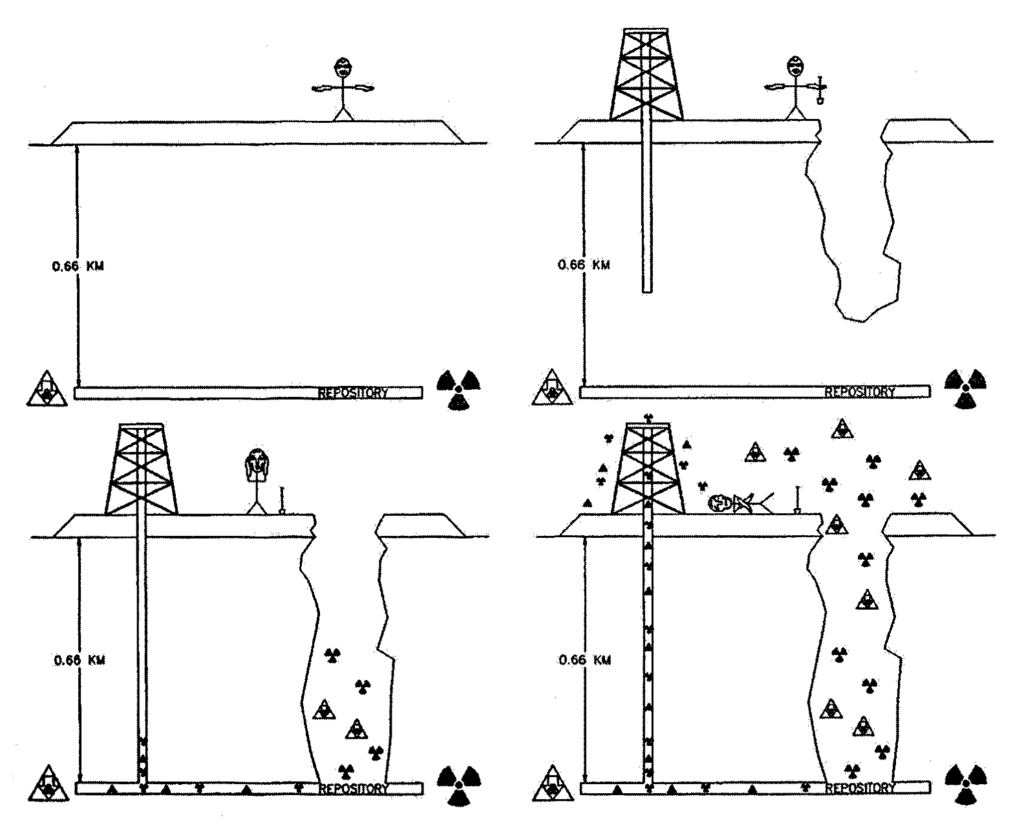

A 1994 proposition of an example of a long-term nuclear waste storage warning sign for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, showing that drilling into the repository could release dangerous radiation. Diagram from the United States Department of Energy.

Propositions for the long-term warning messages on these sites have to balance two things which are both true: 1) it will be easiest to communicate the message in plain language if the future generations understand that language and 2) since there is no guarantee that any particular language will be understood in the far human future, pictorial designs may be best. Thus, the obvious solution is to have a mix of both written and pictorial messages, as well as hostile architecture. The message that opened this article is one example of a written message composed for WIPP. It explains that there will be danger if the repository is opened and that it contains nothing of value that would make doing so worth it, but it does not get caught up in explaining overly complicated technicalities of nuclear waste. There is no guarantee that any particular language will carry down intelligibly into the far future so messages are to be translated into several in parallel to raise the likelihood that one is either known or close enough to a future extant language to be easily deciphered. The list of languages used by WIPP planners includes English, Spanish, French, Russian, Arabic, Mandarin, and Navajo. Because these languages will be written in parallel, it also has the potential to be a sort of future Rosetta Stone where what is known from some languages can be used to translate those which are not known so that various messages from our time can be more easily read. The image above this paragraph on the other hand is an example of a pictorial representation of the danger which requires little or no linguistic understanding to interpret. It creates a simple progression, in parallel, of digging or drilling to the depth of the repository (which is written in metric units in case future viewers are familiar with the measurement system) and shows that breaching the repository can cause a release of dangerous material that can kill the excavator and pollute the environment. One problem the image brushes aside is that there is no guarantee that some of our abstract symbols such as ☢ for ionizing radiation are themselves purely cultural and there is no guarantee that future civilizations will be familiar with them. Designing these messages is playing a game of maximization in which we hope the messages’ readers are more familiar with our historical period than not to make them easier to read but know we can’t rely on them being that way. What if industrial civilization as we know it suffers a breakdown in the future and significant scientific knowledge is lost? These messages need to work even with a culture which does not know what radiation is.

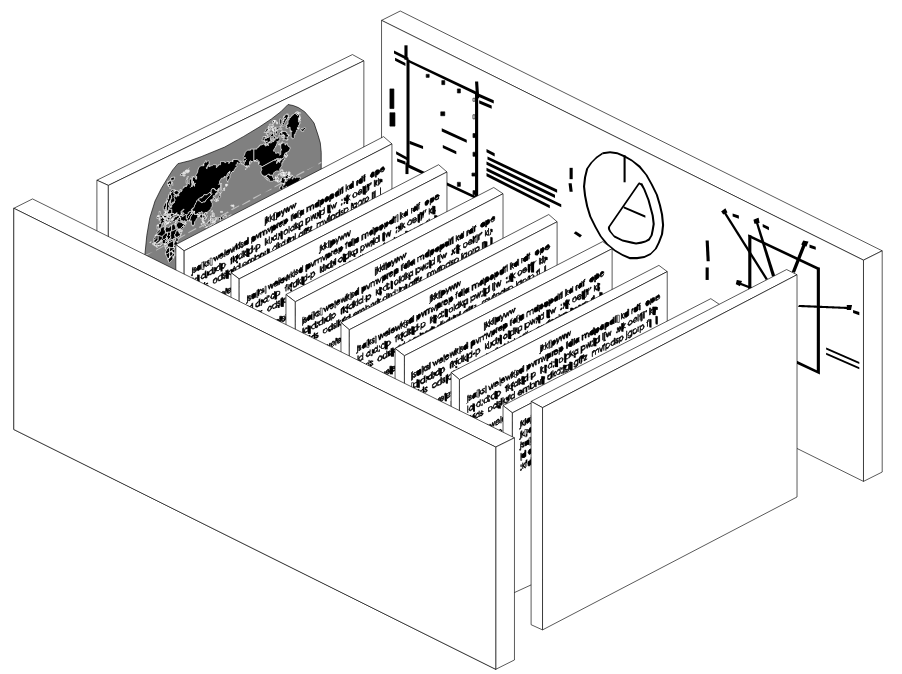

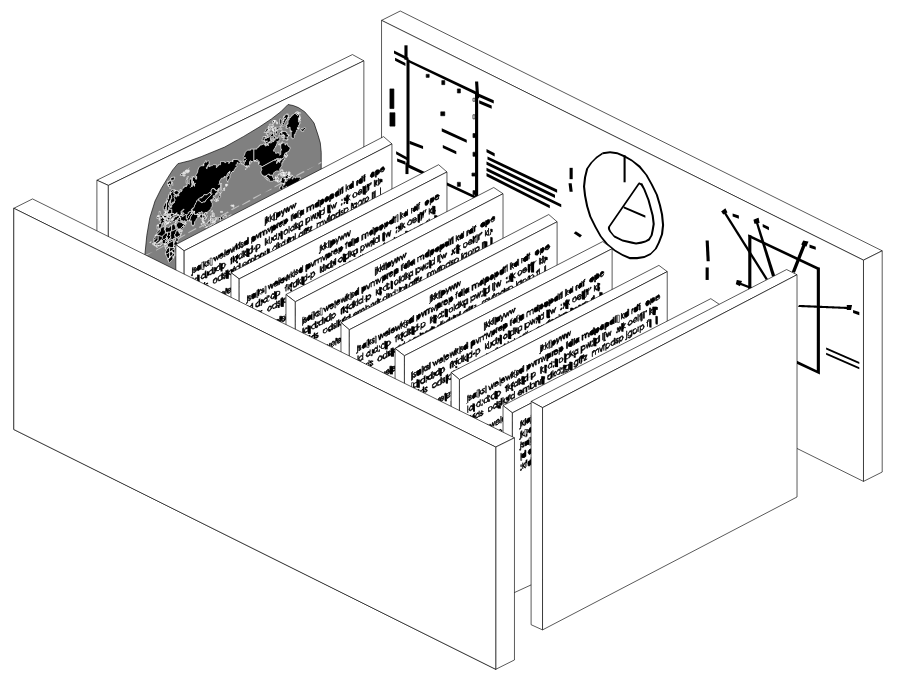

Proposed design from 2004 by the United States Department of Energy for an “information center” to be placed atop WIPP.

Aside from simple inscriptions and buried messages, perhaps some monumentality is warranted, constructing structures atop the sites that will become ancient landmarks. In a publication from 2004, the DOE highlighted some ideas for this. One of the most recognizable in discourse on the topic is the information center as depicted above, to be built on the surface at the geographical center of WIPP with walls of granite buried protectively in caliche soil at a depth of just under two meters. The buried structure has an open top, meaning that once excavated, its contents will be able to be viewed from natural sunlight. Information panels will relay warnings in the seven languages outlined before and explanatory notes for readers capable of making use of them will provide further information on what lies below such as a schematic diagram of the layout of the repository. It has also been suggested that the site could be marked with a monumental surface marker composed of two large engraved stones: one rectangular one which protrudes from the ground into the air like an obelisk and the other being something like a stand for it buried underneath it with the same information. This way the monument has a fully visible component and one protected by the ground. In total, this monument would be about 13 meters high and engraved with similar information to any of the others. Since the passage of time will see changes in language and culture as well as needs and considerations, many planners have suggested that markers should be subject to regular edits and additions by future generations entrusted to the task. This way, future people will be able to understand the warning signs through the lens of their contemporary culture and civilization. It also means that whenever that chain of stewardship is finally severed by unforeseeable historical processes, the next civilization to happen across the site will have warnings from people closer to their time and context whom they will likely better be able to understand than us. Of course, there is no way to know what those we leave these sites to in the near future will think about them so multi-generational stewardship plans like these will probably be more affected by the perspectives of our heirs than us. Will they be responsible by our standards? Are we responsible by theirs?

But what if we are thinking about this entirely wrong? What if marking these sites at all increases the danger? An alternative but legitimate school of thought I have largely glossed over thus far is that human curiosity makes notifying far-future generations of these sites do more to encourage intrusion than to keep it away. When Onkalo opens, it will be able to accommodate about a century of Finland’s nuclear material and if Yucca Mountain ever opens, it will only be able to hold approximately the US’s high-level nuclear fuel waste that exists right now before being filled. Every one of these facilities has a limited capacity and at some point will become filled and finally closed. Once that happens, no matter what is on the surface above, obligatory ancient ruins come into being below. Since antiquity, humans have been raiding the ruins left by earlier humans out of curiosity and interest in treasure. Despite their popularity in media, curses inscribed on Egyptian tombs are extremely rare and when they do appear, such as on some Old Kingdom private tombs, they generally invoke the relatively imperceptible disfavor of the gods on those who venture in. This has not stopped people from believing these sites were cursed for thousands of years and it also has not stopped them from being raided for thousands of years. The Giza pyramids were already emptied by the time ancient Greek writers commented on them and it was buried and forgotten locations like the Tomb of Tutankhamen that made it to the modern period undisturbed. Maybe, this other perspective says, we should hide these places as well as possible from our curious descendants and hope they never stumble upon them because the fact that they are known about increases the chances of disturbance more than leaving them unmarked does. It is impossible to quantify these two likelihoods in the present.

As we round out our exploration of long-term messages, I want to turn brief attention to another sort. The question of how to relay a message to a far-future dissimilar civilization is not actually a question nuclear engineers thought about first and it was approached with other aims by another field of science years earlier.

STATEMENT

This Voyager spacecraft was constructed by the United States of America. We are a community of 240 million human beings among the more than 4 billion who inhabit the planet Earth. We human beings are still divided into nation states, but these states are rapidly becoming a single global civilization.

We cast this message into the cosmos. It is likely to survive a billion years into our future, when our civilization is profoundly altered and the surface of the Earth may be vastly changed. Of the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, some — perhaps many — may have inhabited planets and spacefaring civilizations. If one such civilization intercepts Voyager and can understand these recorded contents, here is our message:

This is a present from a small distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.

Jimmy Carter, President of the United States of America

THE WHITE HOUSE, June 16, 1977

The cover to the Golden Record attached to spacecrafts Voyager 1 and 2 in an image from NASA. The gold-plated copper disk protects the record itself from micrometeorites and is inscribed on both sides with the displayed diagrams, which explain, hopefully, how a machine should interpret the audio and visual contents contained therein, as well as the spatial relationship between the Sun and various pulsars that can help to identify where Earth is.

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were both launched in 1977 by NASA to take photos of the outer planets and their moons, a new step into exploring the universe by a species which less than a decade earlier had first left footprints on the Moon. Both crafts were successful in their missions, the former collecting new data on Jupiter, Saturn, and Titan while the latter managed to collect data on Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The trajectory of these crafts made for an interesting and novel detail however: they were not coming home. Escaping the gravity well of our Sun, Voyager 1 became the first man-made object to leave the Solar System in 2012 with Voyager 2 following it in 2018. Anticipating this, NASA, in collaboration with the United Nations, had compiled the Golden Record, a disk to be affixed to both crafts filled with images and sounds from Earth, both natural and cultural. The disk opens with an image of the message from Jimmy Carter quoted above followed by diagrams on how to interpret our systems of measure as well as our notation for things like the elements, useful for encoding details like biological information and scaled images. Images show natural landscapes and organisms, scenes from cultures around the world, different growth stages of human life, and more. Audio includes a greeting from the secretary-general of the United Nations, animal and natural noises, greetings in a vast array of languages from around the world, and a selection of music. Since the disk was to be affixed to the outside of a craft moving tens of thousands of kilometers per hour, it needed to be protected from space debris with a cover, which itself was engraved with design instructions for a device to play the contents of the disk as well as a map of where the Sun is in relation to several known pulsars, with a binary sequence identifying these pulsars in accordance with their rotational periods. Since the missions of the Voyager crafts were much closer to home than the crafts are now, they are not aimed at anything particular in deep space and will probably wander the Milky Way for perhaps billions of years (though they will no doubt take significant damage in this time). 40,000 years from now, Voyager 1 will pass within 1.6 light-years of the star Gliese 445, which is currently 17.1 light-years from Earth and in 300,000 years it will pass within less than 1 light-year of TYC 3135-52-1. While the stakes are vastly lower for our descendants than the nuclear warning messages we’ve focused on, Voyager attempts to send a message to a time so far in the future and so distant in space that we can only fathom what will happen if it is ever found out there and how the receivers of our gift will make use of the knowledge it holds.

When We’re Gone

We are not at the end of history and indeed the concept of such a thing is almost nonsense. The human story grinds on and so does the story of the natural world around us. Technologies develop, languages evolve, civilizations rise and fall, landscapes shift, life-forms evolve and fossilize and die out, and the very bodies in the heavens soar every way through the great void. Industrial civilization is a tiny sliver in the history of our species thus far and compared to the history of our planet practically nothing. And yet it has already imposed developments onto the world that will intensely define everything about the future of our species and leave a fairly unique layer in the rocks for billions of years to come. Nuclear energy is on the rise and probably has a future as our modern society grapples with how to power itself while avoiding the worst potentialities of rapid climate change. But this decision demands we reckon with the commitments it requires to future generations. We are putting a danger into the world and ensuring the well-being of our descendants may rely on learning to write very long-term messages to them. We will not be here to see what happens when these places are interacted with in 10,000 or 100,000 years. No matter how well we communicate our era to the people of these times, they will know more about us than we do about them just on account of having our remains while we have the unknown of future history to guess across. But in all likelihood, there will be new civilizations that come next and we live in an age where we are able to think of our moral obligations to them and reach out to extend them our well-wishes. Is this not a bit exciting?

Further Academic Reading

- “Accident Investigations of the February 14, 2014, Radiological Release at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, Carlsbad, NM.” United States Department of Energy Office of Environment, Health, Safety & Security, 2015. Accident Investigations of the February 14, 2014, Radiological Release at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, Carlsbad, NM | Department of Energy

- Ford, Aaron, D. “The Fight Against Yucca Mountain.” Nevada Attorney General Aaron D. Ford website, 2021. The Fight Against Yucca Mountain (nv.gov)

- Gil, Laura. “Finland’s Spent Fuel Repository a ‘Game Changer’ for the Nuclear Industry, Director General Grossi Says.” International Atomic Energy Agency, 2020. Finland’s Spent Fuel Repository a “Game Changer” for the Nuclear Industry, Director General Grossi Says | IAEA

- Greaves, Hilary and MacAskill, William. “The case for strong longtermism.” Global Priorities Institute, 2021. The Case for Strong Longtermism – GPI Working Paper June 2021 (2) (globalprioritiesinstitute.org)

- Hart, John et al. “Permanent Markers Implementation Plan.” United States Department of Energy, 2004. Permanent Markers Implementation Plan (energy.gov)

- Ialenti, Vincent F. “Adjudicating Deep Time: Revisiting the United States’ High-Level Nuclear Waste Repository Project at Yucca Mountain.” Science and Technology Studies, 27(2), 2014: 27-48. ss2_2014_kannet.indd (elsevier-ssrn-document-store-prod.s3.amazonaws.com)

- Kristensen, Hans M. and Norris, Robert S. “Global nuclear weapons inventories, 1945-2013.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 69(5), 2013: 75-81. Global nuclear weapons inventories, 1945–2013 (tandfonline.com)

- Nolin, Jan. “Communicating with the future: Implications for nuclear waste disposal.” FUTURES, 1993: 778-791. https://www.academia.edu/download/50808189/0016-3287_2893_2990024-n20161209-21905-u431e7.pdf

- “Nuclear Share of Electricity Generation in 2023.” International Atomic Energy Agency, Power Reactor Information System, 2024. PRIS – Miscellaneous reports – Nuclear Share (iaea.org)

- “Our History.” Nevada National Security Sites, 2024. Our History – Nevada National Security Site (nnss.gov)

- “Our Methodology.” Svensk Kärnbränslehantering, 2021. Our methodology – SKB.com

- Petrov, Yu. V. et al. “Natural nuclear reactor at Oklo and variation of fundamental constants: Computation of neutronics of a fresh core.” Physical Review 74(064610), 2006: 1-17. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/M-Onegin/publication/226532068_Neutron-Physical_Calculation_of_a_Fresh_Zone_in_the_Natural_Nuclear_Reactor_at_Oklo/links/54f848060cf210398e955913/Neutron-Physical-Calculation-of-a-Fresh-Zone-in-the-Natural-Nuclear-Reactor-at-Oklo.pdf

- “Reducing the Likelihood of Future Human Activities That Could Affect Geologic High-Level Waste Repositories.” Human Interference Task Force, 1984. 6799619 (osti.gov)

- Trauth, Kathleen M.; Hora, Stephen C.; and Guzowski, Robert V. “Expert Judgment on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant.” Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories, 1993. Expert judgment on markers to deter inadvertent human intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant – UNT Digital Library

- Von Winterfeldt, Detlof. “Preventing Human Intrusion into a High-Level Nuclear Waste Repository: A Literature Review with Implications for Standard Setting.” Committe on Technical Bases for Yucca Mountain Standards of the National Research Council, 1994. Draft “Preventing Human Intrusion Into a High-level Nuclear Waste Repository, A Literature Review with Implications for Standard Setting.” (nrc.gov)

- Waste Isolation Pilot Plant official website: U.S. Department of Energy’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant – Home Page

- Voyager Golden Record https://goldenrecord.org/

Living in the Longue Durée is part of the History Nerds Network, a group of friends who together make history content online. Check out our Discord server here if you’d like to chat with us: https://discord.gg/dzdrzUpKeG You can also follow for post updates on the Facebook page ( https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61559902349797 ) or on Instagram at @livinginthelongueduree .

Consider supporting my time and money investment into research on Patreon if you want to allow articles like this to maintain their quality and regularity: Living in the Longue Durée | A thoughtful and eclectic history blog. | Patreon

Leave a comment