The date is 9.12.11.5.18 and K’inich Janaab’ Pakal is dead. As the great king of Palenque who ruled for an incredible 68 years is carried to his tomb and the crowds watch on, mourning the deified ajaw, he wears a marvelous jade burial mask and ornately beaded necklaces. He is placed in a colossal stone sarcophagus in the massive House of the Nine Sharpened Spears. Five individuals are sacrificed outside to accompany him to Xibalba, the realm of the dead.

As a priestly scribe, you are in the temple for the rituals and can observe the eerie interior by the flickering firelight. On the lid of Pakal’s sarcophagus, he is depicted ascending the cosmic tree and bridging the gap between the heavens and the earth. Around the edge of the lid is your handiwork, the glyphic writing in the Ch’olti’ language, painted so as to accentuate its color, as much visual art as it is purveying linguistic information. For much of the later part of Pakal’s reign, you have overseen his monumental inscriptions and ensured that the stone-carvers who put them onto structures did them legibly and correctly. The result is a true display of his achievements.

And the record of these achievements will prove in time successful. The record of dates using the Long Count calendar will one day allow researchers to identify this date as August 29, 683 AD. The length of his reign, its key events and achievements, many details regarding dynastic relations, and the ideology of kingship will all be recorded in monumental inscriptions. They will tell of mythological quests and display linguistic developments that demonstrate both the long cultural continuity of your world and its resistance to stasis. For these far future researchers, this Maya written tradition will make this region of the Americas the only part in this period which can be analyzed in the traditional field of history and not purely as a function of the material record.

A Historiographical Note on Writing

Writing is an ubiquitous technology in the modern world and it is easy to passively assume it is somehow natural to the development of a society. In fact, when highly influential Australian archaeologist V. Gordon Childe listed the characteristics of civilization in the early 1900s, he included writing among them and for many decades after, this paradigm was used extensively. The field no longer uses this restrictive view and instead has refined its way of looking at the relationship between writing and civilization. One thing to note is that while writing has been prolific at propagating itself, its actual invention has been rare with only four relatively uncontroversial origin points. The earliest of these was traditionally considered to have been in the Uruk period (4000-3100 BC) of the Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia where an early form of the cuneiform script, pressed into clay, came to be used increasingly after around 3200 BC amongst the world’s first truly large-scale cities. Getting off the ground around the same time was the hieroglyphic writing system of Egypt, which was formerly assumed to have been developed through the cultural inspiration of Mesopotamia but which newer research of very old texts from the Naqada III period (3200-3000 BC) has come to support an independent indigenous origin of the technology that predated significant Mesopotamian influence there, some scholars going so far as to hint that Egypt may have done it first. Outside of the Near East, the first region to invent writing was China a millennium and a half later, where it begins to appear in the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC) in small forms such as the writings on oracle bones. The final region to develop writing was Mesoamerica, which possibly had some form of writing first among the Olmecs from around 900 BC at least and later among the Zapotecs and Maya, the subjects of this article, as well. The oldest likely examples of formative Maya glyphic writing date to between about 300 and 150 BC, coming into existence long after Maya urbanism had begun.

This is all a somewhat simplified version of the story though because defining writing is notoriously difficult among anthropologists in a way that can be applied to diverse systems across the world. Holes in our knowledge can be problems too. For example, the glyphic system of rongorongo from Rapa Nui (Easter Island) may constitute another independently invented form of writing in Polynesia but as it remains undecipherable, if it does record language is currently impossible to assess. Another high-profile case is quipu, a type of artifact from the Andean region of South America which consists of knotted strings that Spanish accounts confirm the Inca used for forms of record-keeping. The fact that these are neither significantly deciphered nor fully understood as to the nature of their contents has made their classification as writing, already non-traditional considering the nature of the medium, fairly touchy. I acknowledge these cases briefly to note that while I find them interesting in their own right (and for reasons too extensive to explore here suspect on the side of certain academics that both were proper writing systems), including them in comparisons to the Maya script here in the way I’ll use Old World scripts would make the subject far too large and complicated. For our purposes, only Mesoamerica had a traditionally defined writing system prior to the early modern period outside of Afro-Eurasia. That said, it was not just the Maya who had what can probably be considered writing in Mesoamerica and that will be explored further below.

We should avoid seeing writing as an inevitable step in a specific place on the development of some civilizational ladder and we should also recognize that as an invention which has been made several times independently, nature does not dictate how writing works and the systems we consider to be forms of writing we are grouping by analogy and not always a direct relation. This is very important as we talk about indigenous writing in the Americas so we can question some of our assumptions about its nature in a place with an isolated experience with it.

A History of the Maya Script

This map by Lynn Foster shows the extent of the Maya civilization in red within the cultural region of Mesoamerica at large, outlined in black.

In the Maya region, as in many other parts of the world, the transition to agriculture and sedentism was gradual. In the Archaic period, defined as lasting from about 8000 to 2000 BC, people throughout Mesoamerica, including in the Maya region, began to settle down into increasingly larger permanent settlements. From 5000 BC onwards, corn appears in the archaeological record of the area and it became an absolute dietary staple, domesticated from the wild plant teosinte into an incredibly productive grain with many uses, accompanied by beans and squash. Historically it was often debated what was the “original” civilization of Mesoamerica that gave civilizational features to all the others with the Preclassic Maya and the Olmecs being the classic examples but today scholars are able to adopt a more multipolar view where many parts of Mesoamerica saw similar developments at the same time and interacted with each other all through it. The Preclassic period is defined for the Maya and Mesoamerica at large as being from 2000 BC to 250 AD and began with the emergence of large-scale cities with the associated economic specialization and large-scale public works projects. Historically, the Preclassic was bookended by the emergence of cities and the emergence of monumental stelae but new discoveries have pushed examples of writing into the later Preclassic and the standard chronological division has still remained in place.

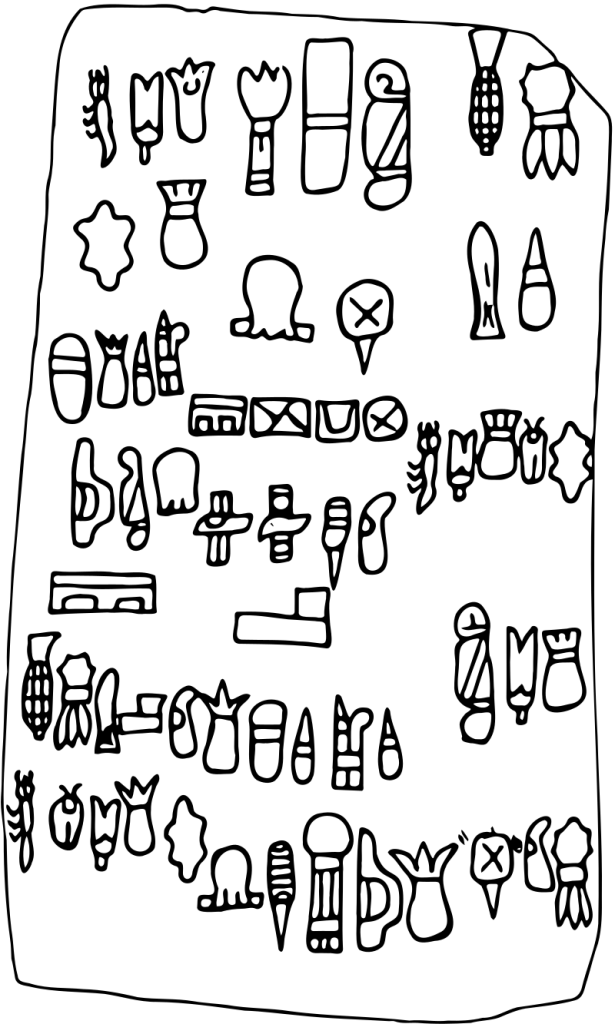

The Cascajal Block, a probable Olmec artifact with 62 characters that may represent the oldest known writing system in Mesoamerica. This is derived from a traced image by Michael Everson.

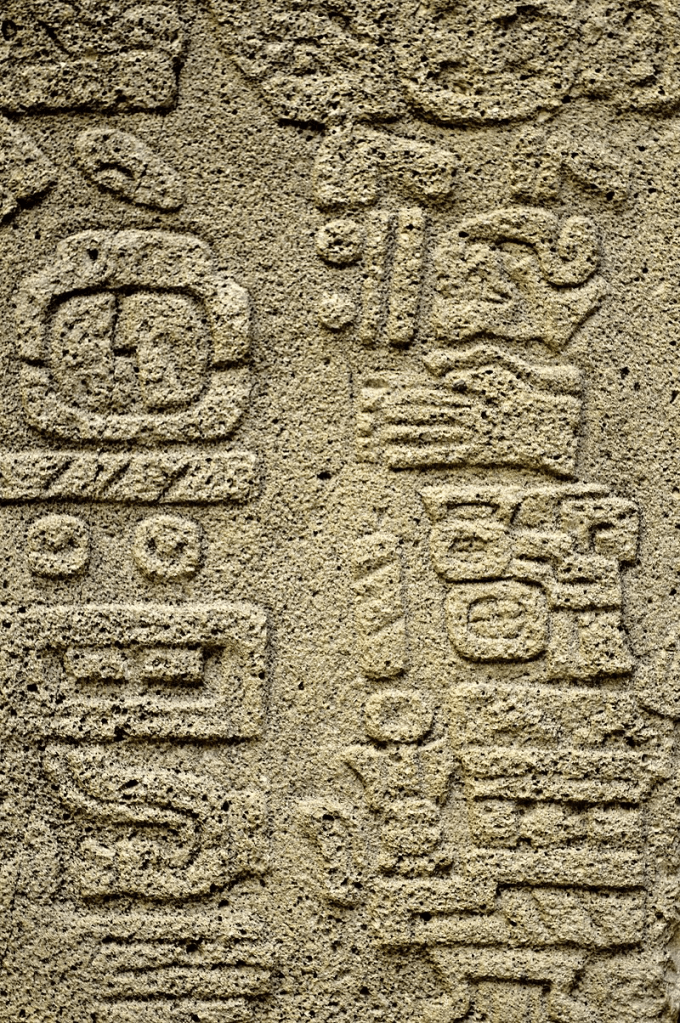

An example of Zapotec writing from Monte Albán in Oaxaca, Mexico, uploaded to Wikimedia by user LBM1948.

The question of the earliest writing in the Americas is a somewhat contentious one but scholars have leaned increasingly more towards it being invented first in the Olmec civilization of 1200 to 300 BC, contemporaries of the Preclassic Maya centered in what is today the Mexican state of Veracruz. Glyphic symbols have been observed but it is unclear if they represent a written script. The most notable artifact regarding this is the Cascajal Block, which supporting scholars have suggested is older than about 900 BC but which skeptics have pointed to dating problems with regarding the fact it was found out of context in discarded rocks. If the glyphs comprise a script, it is as yet utterly undeciphered. Among supporting scholars, a debate exists as to the orientation of the text with some supporting a left-to-right bottom-to-top reading order with the orientation it is pictured in above. Another suggestion holds that the above image needs to be rotated 90 degrees to the left and then read with a left-to-right top-to-bottom reading order that way, more akin though not exact to later Mesoamerican scripts like that of the Maya. As an emerging and controversial area of scholarship, the relationship between any potential Olmec writing and the considerably more understood writing of the Maya is difficult to comment on. Also not considerably deciphered but far better conceptually understood is the system of writing of the Zapotec civilization, which flourished in what is now the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca from around 700 BC until Spanish conquest, sometimes within the sway of other Mesoamerican political entities like that of the Aztecs. At the Zapotec site of Monte Albán in what archaeologists have termed Phase I at the site (500-200 BC), evidence exists for the emergence of a system of writing that developed fairly early. At this point, based on patterns of usage and relation to the Maya system, researchers are able to understand the meaning of certain glyphic symbols in Zapotec writing, especially the glyphs representing certain city-states like Monte Albán (which seems to have been the center of a small empire in the later Preclassic), though the pronunciation of these glyphs remains unclear. Some of them appear to have variable parts, which might indicate that they changed to fit grammatical elements of the script. The script was read similarly to the Maya script, vertically in columns. In the early Classic period of Mesoamerica (250-900 AD), the city of Teotihuacán just north of modern Mexico City became the center of an empire and a major immigrant center with quarters of the city representing the material culture of many parts of Mesoamerica. Here as well the Zapotec script makes an appearance in the Zapotec quarter of the city. For reasons that are somewhat unclear, the Zapotec script fell out of use towards the end of the Classic period, though it seems to have impacted the iconographic traditions of other Central Mexican peoples like the Mixtecs and Aztecs.

The earliest example of Maya writing in the known material record appears to be from the site of San Bartolo in modern Guatemala. Stone can’t be radiocarbon-dated and therefore writing on stone generally has to be dated by content and context, the excavators of this site suggesting based on the carbon-dating of accompanying burnt wood remains that the inscription was probably made between about 300 and 200 BC. The writing consists of ten painted glyphs which show clear connection to later Maya writing but have not been wholly translated themselves, though the glyph for AJAW, the Classic Maya word for a semi-divine king such as Pakal at the opening of this article, appears recognizably. Perhaps even at this early phase, Maya writing was associated with celebrating rulership. The urban complexes of the Preclassic world were not to last too many centuries longer though and around 100 AD, a general urban collapse happened throughout the Maya world. With the opening of the Classic around 150 years afterwards, the major urban centers of the region would be new cities. The use of the glyphic writing system though would explode.

This stela from 731 AD celebrates the ruler Yuknoom Took’ K’awiil who reigned over the Classic city-state of Calakmul from 698 to 736 AD during a period of the city’s hegemonic power over much of the Maya world, evidenced by other kings’ inscriptions noting their allegiance to him. This picture is by Wikimedia user Thelmadatter.

With the coming of the Classic period (250-900 AD), the Maya entered their most famous phase of history for us today, popularly considered the height of their civilization. Part of the reason for this is the sheer number of monumental stone inscriptions, inordinately celebrating the deeds of the ajaws, who became central to the political-religious systems of Maya cities. Because of the extensive stone written record, we are often able to attribute monuments to specific rulers, assess the dates and lengths of rulers’ reigns, read about specific wars and alliances, and reconstruct a political history of the period in a way that is generally not possible in the rest of the Americas this far before Columbus. For students of ancient history who prefer written texts over archaeology, the Classic Maya are easily the most accessible civilization to research in the ancient Americas. Aside from temple inscriptions, the most famous form these inscriptions took were stelae which adorned public spaces and celebrating significant achievements but also notable rituals. Stelae actually stylistically vary a lot and it is clear they did not necessarily adhere to strict rules but could be a very creative artistic medium, even if they were propagandistic. From these stelae we know for instance of occasions when kings participated in certain religious rituals such as bloodletting (blood was considered to be a sacred life force and elites were religiously obligated to sacrifice some of their own in offerings to the gods) and even religious dancing performances. Stelae are almost always dated using the Long Count calendar, often noting the end of some period or event being commemorated. Because of this, we often have a better grasp of the exact dates of events than we do of some things in contemporary Eurasia for instance.

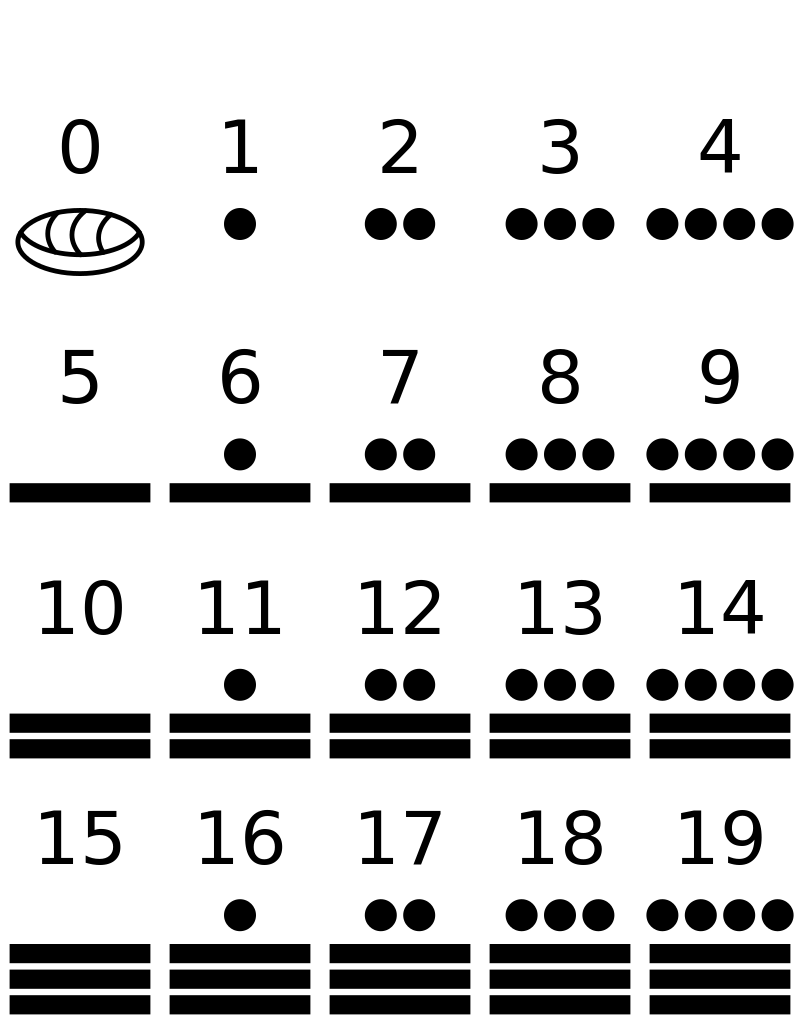

Above are Maya numerals, in a graphic produced by Neuromancer2K4 for Wikimedia. Accompanying glyphs, these numerals are what is used in notating inscription dates. The inclusion of a zero is often celebrated as a relatively early integration of the concept into a numeral system.

Because these inscriptions are the most notable ones in the study of Classic Maya script, it is necessary to understand the Maya Long Count calendar. My first exposure to this calendar when I was younger related to the buzz around the supposed end of the world on December 21, 2012 that was widely reported as being predicted by the Maya. In reality, this was not the case and what was ending was the 12th b’ak’tun, or cycle, of the Long Count calendar. The Long Count was, and still is, used by multiple Mesoamerican peoples and not just the Maya but the Maya form of it is the most well-known. It consists of the counting of individual days within larger cycles that can be counted and add up together to produce dates. Because the calendar is still used and kept by indigenous people today, it is possible to project it deep into the past and identify the specific dates recorded in inscriptions. The smallest unit is the k’in which is a single day. 20 of those compose a winal. 18 of those compose a tun (360 days, close to 1 year). 20 of those compose a k’atun (7,200 days, close to 20 years). And 20 of those compose a b’ak’tun (144,000 days, close to 394 years). There are actually higher levels that continue to extend the calendar into units of billions of years but these are not generally kept in monumental inscriptions. Dates are notated with a series of numbers for each unit, representing which one the date is at in the cycle. As of writing this, the date is June 9, 2024 which has a Long Count date of 13.0.11.11.8. You can use this website ( Maya Calendar Converter | Living Maya Time (si.edu) ) to explore date conversions, as well as how to write them in Classic Maya glyphs, yourself if you feel so inclined.

Important to note also in this period is the important role of scribes, those who had the specialized knowledge required to design inscriptions in the first place. Unfortunately, Spanish accounts tended to take poor interest in scribal culture when they recorded the lives and traditions of the Maya they interacted with. We thus are left with a partial knowledge that is supplemented by how scribes are depicted in art and what is known about them in other Mesoamerican cultures. While scribes were not afforded as much prestige as the rulers of Maya society themselves, they were certainly closer than most people and Maya artworks seem to give scribes a very important reputation in society and even an amount of reverence. Scribes had a lot of power over how kings were remembered and the public legitimacy they derived from connections to previous kings and to the gods. As court figures who worked closely with the government, they would have probably had significant influence in the halls of power. Recently it has been argued that scribes were not only influential and powerful but also fairly autonomous, specialists who dominated their domain and conducted a very important organ of the state that essentially required their specialized and somewhat esoteric knowledge. After all, in a society where the vast majority of people couldn’t read, writing was something the literate few were not only the creators of but also the purveyors of to the masses like seers with special access to an incredibly special form of knowledge.

The Classic Maya collapse between 750 and 900 AD is as wildly misrepresented in popular literature as it is debated in academic circles. For whatever reason, it is often written about online as a mysterious and sudden disappearance of the Maya civilization, despite the facts that the most popular Maya tourist site (the Temple of Kukulkan at Chichén Itzá in the modern Mexican state of Yucatán) is a Postclassic monument, the records of Spanish conquistadores include their interactions with powerful Maya states, and there are about 8 million ethnic Maya today. In reality, the collapse was a period of the breakdown of major urban centers over about a century and a half. Increasingly popularly, scholars have looked at factors relating to both climate (such as increased drought in the period) and anthropogenic activities like deforestation as leading to increasing state failure as cities’ systems were stressed to a breaking point. There are scholars who also disagree on these ideas and diving into the collapse would be too intensive of a topic to cover here. Regardless, Maya civilization experienced a radical reshuffling, including a change in most of the major urban centers, and then continued. For our purposes, the collapse is important in that it saw the end of Maya monumental inscriptions, accompanied by less large-scale constructions in general, and a population decline that followed the collapse of major cities. It seems that in this period, the institution of divine kingship faded and the institutional demand for declarations of royal glory and achievement were not as present.

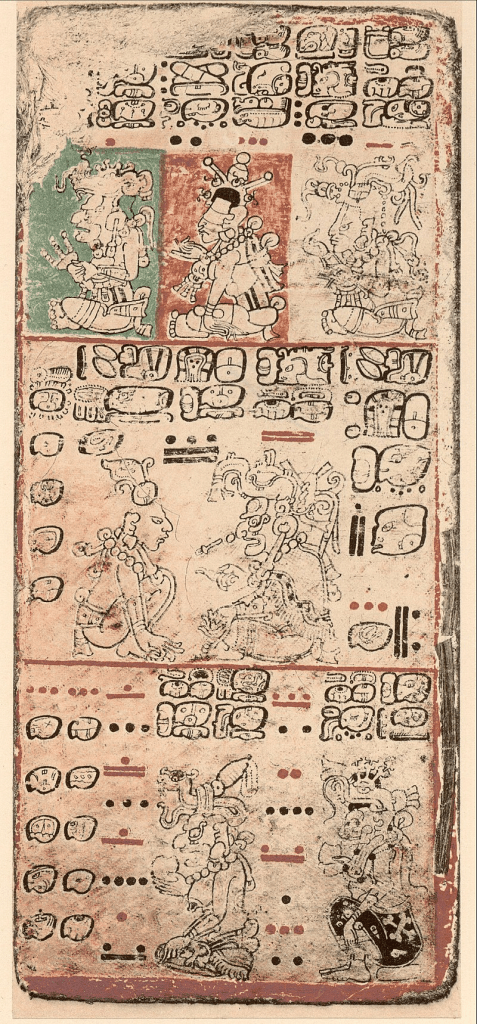

Page 9 of the Dresden Codex, which dates to around 1200 AD.

The Maya world opened on the Postclassic, a period of Mesoamerican history considered to run from around 900 AD to the Spanish capture of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1521. The Postclassic Maya built new urban centers but did not centralize kingship in the same way as before. The disappearance of Maya writing from the archaeological record is a bit of an illusion here because while monumental stone inscriptions ceased, codices on bark paper (short fold-out books essentially) were made but have proven either very perishable with time in the hot humid tropical environment or specifically destroyed by the Spanish as we shall discuss soon. Only four significantly preserved Maya codices are known today, the physical copies all dating likely to the last century of the Postclassic before colonization but the texts themselves generally being copies of older documents, mostly of the Late Preclassic, though some original text dates have been suggested as early as the Classic, though this is a minority opinion. Fragmentary remains of other poorly preserved codices have been found as well. Despite the scant nature of the evidence, they provide clear examples of a paper literary tradition and we can reasonably assume that in Pre-Columbian times, they were far more common. All four extant Maya codices contain at least in part what scholars have come to term almanacs, organized descriptions of rituals or events tied to different astronomical positions and calendar dates, demonstrating the sacred role of Maya timekeeping, all laid out in easy-to-read tables. This codical tradition was still in practice in 1517 when the Yucatán Peninsula of modern Mexico, increasingly the center of gravity in the Maya world in the Postclassic, came into the historical record of Europeans… or sort of.

The popularly accepted first European exploration of the Yucatán was carried out by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba in 1517, coming from Spain’s colonial presence in Cuba, sailing along the north and then west coast of the peninsula, sailing off to Florida, getting back to Cuba, and promptly dying. Córdoba had intended to subject the Maya world to the Spanish encomienda system, a sort of feudal slavery that conquistadores impressed onto native peoples in New Spain in the lands they took over. Instead, he managed to get into some light fighting with the Maya and do very poorly, taking heavy losses before taking more in Florida. It was a sign of how hard the region would be to subject to colonial rule. In fact, scholars no longer believe that Córdoba was the first European in the region. It seems that Christopher Columbus himself may have briefly gotten there first in his fourth and final voyage in 1502. And one of my favorite strange minor characters of history, Gonzalo Guerrero, was a Spaniard who became shipwrecked in the region in 1511 and assimilated into Maya culture, possibly fighting in native forces against Córdoba in 1517 before joining up with the now more famous Hernán Cortés when he passed through in 1519 on his fateful journey to the Aztec Empire to the west. Even if Córdoba wasn’t the first Spaniard in the region, it is after him that the conquest of the region began. In 1527 and again in a three-year expedition starting in either 1530 or 1531, Francisco de Montejo the Elder made his attempts at real conquest, getting repulsed by the locals yet again. It was his son, Francisco de Montejo the Younger, who managed to put the first permanent Spanish settlements in the region starting with San Francisco de Campeche in 1541. A Maya rebellion arose in 1546 and with its defeat the next year, the colonization process intensified.

Different parts of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, and colonial relations with local people, were administered differently in a somewhat haphazard manner. In the Yucatán, administration was put in the hands of the Franciscans, a Catholic monastic order, who were tasked with evangelizing the Maya to Catholicism. (Keep in mind that under this period of administration, the conquest was still an incomplete process: the Maya world was always politically fragmented and at least some cities would remain independent until 1697. I am also focusing here specifically on the northern part of the Maya world.) 165 towns were organized under Spanish rule by 1560 and a representative system was built in which members of the communities would come to a sort of combined government, though the new ruling order always prioritized Catholicizing the public, organizing an educational system to do so and strongly discouraging local religion. All the while, severe disruption of local ways of life and the spread of epidemic diseases caused an incredibly sharp decline in indigenous population. In 1562, the local head of the Franciscans and effective governor of this part of the empire, Diego de Landa, became aware of indigenous religious objects being hidden away for use near the town of Maní. Furiously, he blamed the education system and subjected its various indigenous teachers and organizers to torture and forced confessions of the Catholic faith. For our purposes in the history of Maya writing, he ordered a widespread destruction of Maya religious materials, including the codices. Aside from deposition, it is also this specific book-burning episode that has left us with so few of these materials to work with. It was also the assault on this tradition and the imposition of the Latin script that caused the Maya glyphs to die out as a usable system. They became an undeciphered writing system as the last generation of their writers passed. However, De Landa’s methods were not particularly appreciated by the Spanish government which recalled him to answer for them. In the process, his notes got transferred to Spain where they ironically became one of the best accounts of Maya life in the period, Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, including a short description of a Maya “alphabet” that would go unnoticed for around the next three centuries but one day help to decipher the glyphs.

For the next few centuries, it was recognized that the Maya monumental stelae represented a writing form but the nature of this was unclear. Drawing on racist ideas of the current Maya as primitive people, the old trope of attributing impressive monuments and writing to foreigners was employed and theories abounded in which the Maya ruins represented to various questionable actors at various times everything including lost tribes of Israel, a trans-Atlantic Phoenician outpost, the occidental outposts of the survivors of Atlantis, or the dispersal of an ancient Aryan master race. The most prominent modern version of this which refuses to die exports credit for Maya achievements off-world to visitors from the stars and plays on large-budget TV stations and streaming services. Real movement in understanding Maya writing began in the 1950s. Before that point, only the numerical system and astronomical calculation had been deciphered, but in 1950 British Mesoamericanist John Eric Sidney Thompson published Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: An Introduction. He claimed that like Aztec writing Maya writing was semasiographic in nature, that is it did not actually record the phonetic elements of spoken language. This publication would dominate the field for some time but a challenger was already emerging on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

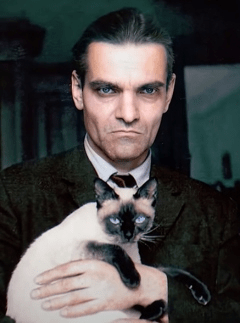

Soviet linguist Yuri Knorozov (1922-1999), the principle decipherer of Maya glyphs in modern times, with his cat Asya. Knorozov always listed her as a contributor on his publications (though editors removed her name) and insisted she be included in publication photos of him. As such, it is only proper that Asya is included with recognition in this article.

Yuri Knorozov had been studying as a linguist in the Soviet Union when Nazi Germany invaded in 1941, postponing his studies while he served in the military. A popular legend among academics and tour guides goes that Knorozov was there as the Soviets captured Berlin in 1945 and that he found a burning library and rescued a volume containing copies of the Dresden, Madrid, and Paris codices, starting his adventure towards revolutionizing Mesoamerican studies in dramatic fashion. Despite this story being widely distributed, an interview with Knorozov from late in his life demonstrates that he considered it untrue, that the German command had simply packed up their archives in boxes but then promptly lost the war, so the captured pre-packaged materials were just taken to Moscow. Regardless, after the war, the young linguist took interest in captured Maya materials and, revisiting notes from De Landa on the Maya “alphabet,” he began to note the phonetic elements involved. Maya writing was obviously far more complex than the small set of symbols De Landa had collected but Knorozov hypothesized that perhaps De Landa had asked a local scribe to write each letter in Spanish and said their names as a Spaniard would have pronounced the letter. Thus what was written for, for example, m was not the sound /m/ but rather the Spanish name of the letter e-me, composed of two syllabic characters. Knorozov used the most common modern Mayan (in academic usage, with an n signifies the language family) language Yucatec as a basis for finding similar words in the ancient language (which is the related but extinct language Ch’olti’). This breakthrough led to more and more syllables being gradually identified, especially as they labeled nearby pictures: tzu-lu near a picture of a dog was like the Yucatec word tzul for “dog” and the final vowel was likely silent as Mayan words don’t tend to end in vowels. Knorozov published these discoveries in 1952, challenging the newly dominant Thompson, who reacted quite angrily. If Knorozov was right, Thompson was very wrong and on top of this, during the height of the Cold War, the idea of Anglo-American academia needing to learn from Soviet academia’s supposed breakthroughs had a politically charged dimension that affected this field as much as many others. Knorozov’s discoveries thus only attracted a small amount of interest in academia at first but with time it would become evident that his methodologies were yielding results as they produced coherently readable monuments. Maya script is not 100% deciphered today as certain unknowns remain but Knorozov is recognized as the figure who made it intelligible once again.

How Classic Maya Script Works

The final section of this article will serve to illustrate how Maya glyphs work, as the writing system is almost entirely distinct from those likely familiar to readers today. My actual academic background is in the ancient Near East, not Mesoamerica, and so my grasp of this topic is based on what can be found in publicly available self-teaching sources. The relevant book recommendation here is Translating Maya Hieroglyphs by Scott A. J. Johnson, which seems to be one of very few useful treatments of the topic that is actually easily accessible to a popular audience. Traditionally when studying the development of writing systems in the Old World, it is common to group writing systems under categories such as alphabetic (having a small number of phonemic characters that are used to spell out how words are pronounced), logographic (having characters that represent whole words or ideas), and syllabary (having characters that represent whole spoken syllables). The Maya script bucks all these categories while having characters that could easily fit in all of them. It is briefly worth noting that the language written with the glyphs is usually a literary form of Ch’oltli’, a now-extinct Mayan language, which is sometimes called simply Classic Maya. Sometimes other Mayan languages are written with the glyphs as well, though modern speakers of Mayan languages generally simply use the Latin alphabet like in Spanish. At present, Maya writing has no Unicode support and so cannot be typed on a computer. This is no doubt because of the challenges of displaying it properly considering the very uncommon direction of text.

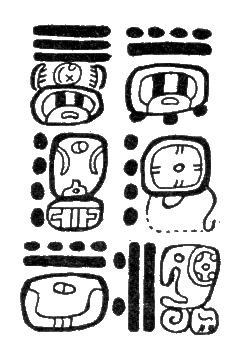

Example of the reading order of Maya glyphs by Wikimedia contributor Babbage.

When we refer to glyphs themselves, we refer to the block-like constructions that appear in Maya writing. These can be as simple in meaning as a single noun to an entire verbal phrase and as such it is not useful to think of individual glyphs as a specific grammatical concept but rather as a way of visually organizing a text. Maya writing is, aside from a carrier of meaning, a form of visual artistry and organization is supposed to have an aesthetic quality to it. The glyphs are organized as a sort of grid in columns and rows (though this is flexible) and every two rows of columns are paired together so that the first two columns are read in a left-right zigzag pattern from the top of the inscription downwards. Once these two columns have been read in this alternating pattern, the reader moves their eyes up to the top of the next pair of columns and reads similarly. If the number of columns is odd and a final one is left or if all glyphs are simply in a single column, the reading direction is just downwards from bottom to top. Within a glyph, there are different “signs” that we can think of as characters and which can be phonetic or logographic. If it makes it easier to conceive of, you can compare Maya glyphs to Korean Hangul where different elements are constructed together into larger reading blocks that themselves require an internal reading order to make sense of. Generally there is a “main sign” which is visually emphasized and takes up about half the glyph and is subject to how the scribe chooses to place emphasis. Affixed signs are placed at the edges (left-and-right or top-and-bottom) and are read either left-to-right or top-to-bottom, depending on how they are arranged within the glyph. At times there are also infixes, affixes placed within the main sign, and technically there can sometimes be no main sign at all, with simply a large number of small elements making up the glyph.

This excerpt from the Dresden Codex uses numbers which are easily identifiable affixes next to their main signs. Since the numbers are read first in all glyphs here, they are placed either to the left of or above the main sign, according to the desired aesthetic construction of the glyph.

Signs within glyphs are often logograms, meaning that a single sign contains the full idea of a word with no particular phonetic implication to sounding it out. At the same time, others are syllabic. Unlike, for example, Chinese Hanzi, they are not necessarily strictly representative of syllables as a linguist might parse them listening to speech but are more like those used in, for instance, Akkadian cuneiform where they represent a chunk of nearby vowels and consonants to build the approximate sound of a word. Sometimes a word can be spelled both ways. In scholarly transliteration, a similar practice is used to transliterating Akkadian where logograms are written in all-caps while phonetic transliteration is written in lowercase with hyphenation between pieces represented by different signs. The sacred kings of the Classic period had the title of ajaw and this can be written both logographically and phonetically. As a logogram, it is transliterated “AJAW” while phonetically it might appear as “a-ja-wa.” Note that the third sign there suggests a vowel that is not part of the pronunciation of the word. Classic Maya words generally end on consonants and often a final phonetic sign will be used only for its initial consonant with an implied vowel being silent. This will tend to be implied through the vowel of the final character matching that of the character preceding it. Phonetic spellings are not standardized and multiple combinations of phonetic elements might loosely build the same word at different times.

Moving past this explanation would require teaching a certain amount of Ch’oltli’ grammar and vocabulary which would go beyond the scope of what I can do justice in this blog. I do encourage readers as always to use the articles on this blog as simple jumping-off points to introduce themselves to the study of new topics. To those who have never taken the time, in school or in free time, to play with an ancient language, it is a worthwhile experience. If Classic Maya is the one for you, then once again I recommend getting started with Translating Maya Hieroglyphs by Scott A. J. Johnson.

Further Academic Reading

- Chanier, Thomas. “The Mayan Long Count Calendar.” 2013. 1312.1456 (arxiv.org)

- Cooper, Jerrold S. “Babylonian beginnings: the origin of the cuneiform writing system in comparative perspective.” The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, edited by Stephen D. Houston. Cambridge University Press, 2004: 71-99. babylonian.pdf (utah.edu)

- Henzlik, Sarah. “Autonomy & Power: Maya Scribes.” The Coalition of Master’s Scholars on Material Culture, 2021. Henzlik_Autonomy+and+Power-+Maya+Scribes_2021.pdf (squarespace.com)

- Hodell, David A.; Curtis, Jason H.; and Brenner, Mark. “Possible role of climate in the collapse of the Classic Maya civilization.” Nature 375, 1995: 391-394. Possible-Role-of-Climate-in-the-Collapse-of-Classic-Maya-Civilization.pdf (researchgate.net)

- Johnson, Scott A. J. Translating Maya Hieroglyphs. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2013.

- Kettunen, Harri J. “Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An Interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part II.” Artekkelit Toukokuu, May 1998. Kettunen: Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An Interview with Yuri Knorozov, part II (archive.org)

- Mora-Marín, David F. “Early Olmec Writing: Reading Format and Reading Order.” Latin American Antiquity 20(3), 2009: 395-412. EarlyOlmecWriting.pdf (unc.edu)

- Quezada, Sergio and Hernández Ortiz, Silvana. “Colonial History of Yucatán.” Voices of Mexico, 2018: 98-102. VOM-0085-0098.pdf (unam.mx)

- Saturno, William A.; Stuart, David; and Beltrán, Boris. “Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala.” Sciencexpress, 2006: 1-3. science.pdf (sanbartolo.org)

- Saville, Marshall H. “The Discovery of Yucatan in 1517 by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba.” Geographical Review 6(5), 1918: 436-448. The Discovery of Yucatan in 1517 by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba on JSTOR

- Stuart, David. “Kings of stone: A consideration of stelae in ancient Maya ritual and representation.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 29(1), 1996: 148-171. Stuart__Kings_of_Stone-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Vail, Gabrielle. “The Maya Codices.” Annual Review of Anthropology 35, 2006: 497-519. The Maya Codices | Annual Reviews

- Whittaker, Gordon. “The Zapotec Writing System.” Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volume 5: Epigraphy. University of Texas Press, 1991: 5-19. Whittaker_-_The_Zapotec_Writing_System_-_HMAI_1992-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

Living in the Longue Durée is part of the History Nerds Network, a group of friends who together make history content online. Check out our Discord server here if you’d like to chat with us: https://discord.gg/dzdrzUpKeG You can also follow for post updates on the Facebook page ( https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61559902349797 ) or on Instagram at @livinginthelongueduree .

Consider supporting my time and money investment into research on Patreon if you want to allow articles like this to maintain their quality and regularity: Living in the Longue Durée | A thoughtful and eclectic history blog. | Patreon

Leave a comment