It’s a January morning on the farmstead and the rising Sun will soon bring in another very hot day. The call of the laughing kookaburra has become a more common sound since its introduction from the mainland a couple years ago in 1906 and it certainly adds to the atmosphere. One shift of organisms in the great Tasmanian landscape is giving way to another as night becomes day.

You’re just a child but standing on the patio of your little family home, you are peeping out into the landscape to try to see the source of the sound that woke you up, the bang of your father’s gun. Now you see him walking back from the chicken coop. He carries in his hand a long animal, orange and with black stripes like a tiger but not much bigger than the family dog. Its limp body hangs from the tail he holds it by with limbs outstretched.

“Is that a tiger?” you ask him.

“Yes, it was near the sheep. It will not bother them again. And the government will pay me a pound when I let them know I shot it.”

You stare at the creature. For a few more decades, you will hear about how sometimes they are present in the area but you do not suspect this may be a historical moment. Because you will never see one again.

Those We’ve Lost

In 2017, Larsen et al. published one of many estimates for the number of species currently alive on Earth. Using different assumptions for the amount of parasites and endosymbionts that must exist for each multicellular eukaryote, they produced four different models for how many species might be expected. In the first of these models, their moderate one, they come to the conclusion that about 2.238 billion species must exist on Earth. These break down to 163.2 million animals, 0.340 million plants, 165.6 million fungi, 163.2 million protists, and 1.746 billion bacteria. This estimate assumes that different proportions of the representatives of different groups of organisms have been discovered (for example, it assumes that only about one in seven insect species has been documented). Different estimates can vary dramatically but one thing is for certain: the amount of species on our planet is utterly vast.

But the number gets even more, almost incalculably, daunting when you take into account the past. Nature is not a static place and we know based on both the fossil record and real-time observation that species both come into existence and disappear from it. Pretty much uncontroversially among scientists, no matter the counts for right now, the number of species that have ever existed in life’s 4.1 billion years is so large that our current global diversity covers less than 1% of it. When we think of extinction, the most famous poster child is perhaps Tyrannosaurus rex or something similar, an animal that has been gone for so long that no human has ever witnessed one alive. And indeed, most types of animals were never witnessed by us. But between the categories of extant species and prehistoric ones, there exists another category comprised of those which the writers, artists, scientists, policymakers, and photographers of history were able to watch in the process of disappearing and leave us with the story.

This is the story of one such animal, the thylacine, Thylacinus cynocephalus, sometimes better known as the Tasmanian tiger. It is a tragic story and, most tragically of all, it is not unique.

Thylacines in the National Zoo in Washington DC, 1904, from the Smithsonian Archives.

An Evolutionary Story

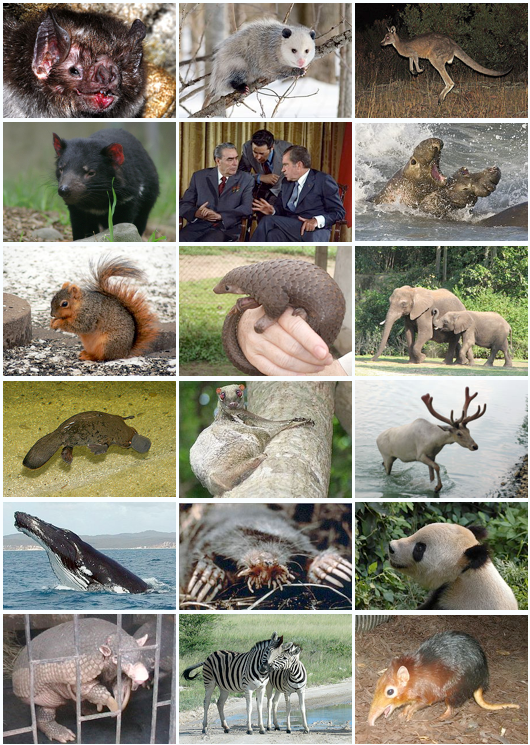

An illustration of mammal diversity from Wikimedia. I choose to include it here both for its illustrative utility and because of my amusement at the compiler’s choice to include Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev as representative mammals, which they indeed are. The marsupials in this image are the second (opossum), third (kangaroo), and fourth (Tasmanian devil) images. The lone monotreme is the tenth (platypus). Every other included mammal is a placental.

Mammals have existed for some 225 million years since the Mid-Triassic Period. To put that into perspective, the dinosaurs appeared about 230 million years ago. The majority of the evolutionary history of mammals thus took place under the feet of the non-avian dinosaurs. Many branches of the mammalian family tree arose in the Mesozoic Era (the so-called Age of Reptiles) and many mammals went extinct in that time or at the end of it in the same cataclysmic event that took place 66 million years ago and deprived us of T. rex and our other non-avian dinosaur friends. All living mammals today fit into one of two clades, both of which date to the Mesozoic Era. Firstly there are the monotremes which today include merely the platypus and four species of echidnas. If egg-laying mammals seem weird to you, it may surprise you to learn that it is an ancestral trait of all mammals and it is the ancestors of the other clade which broke from their egg-laying heritage. Platypuses and echidnas are the last of something truly ancient. All living mammals besides these fall into the therians, a group which shares common ancestry somewhere in the Early Cretaceous Period (145-100.5 million years ago), though due to only a few specimens being known in the fossil record from the basal members of this clade, the exact timing on a last common ancestor is controversial. From here we can group all living therians into two major groups: the placentals (part of an older clade Eutheria) and the marsupials (part of an older clade Metatheria). Placentals, a group so significant that it includes you the reader, have unquestionably become the dominant form of megafauna in the world as the dinosaurs have lost that role and they make up the vast majority of mammal species. But the subject of our story today is the marsupials, which unlike placentals give birth to only partially developed young called by the wonderfully Australian moniker of “joeys” which then migrate or are moved to an external pouch on the mother to continue their development.

There is a bit of a debate as to whether the last common ancestor to all marsupials lived before or after the catastrophic asteroid impact at the end of the Mesozoic, 66 million years ago, but the molecular genetic study I used as a source from Meredith et al. posits that this missing ancestor lived under the reign of the dinosaurs and their ancestors had certainly diverged from those of placentals by 173 million years ago much earlier based on fossil evidence. The original home of marsupials was South America, a continent which at the time was closer to Africa across the thin Atlantic than it was to North America. It was the proximity of the southern continents which perhaps most decided where marsupials would find themselves distributed. (For those who would find a 3D model of continental drift useful here, I recommend the website GPlates: GPlates Cesium .) To generalize, the marsupials would have two major regions of development, in South America and Australia, both of which were relatively isolated for most of the Cenozoic Era (the last 66 million years). Modern species outside of these regions (opossums in North America and possums in Southeast Asia) are recent dispersals from these centers of development from the last few million years. Most continents became dominated by placental mammals but these two continents continued to see marsupials survive and thrive, though by today that is mostly just the case for Australia.

Thylacines were a type of Australian marsupial called dasyuromorphs which also include quolls, numbats, dunnarts, and the Tasmanian devil. These animals are all carnivorous and have come to take ecological niches similar in many ways to those taken by placental carnivorans in Afro-Eurasia and the Americas. They vary in size but only get so big. The thylacine, similar in size to a large dog, was the recent biggest with the six-to-eight-kilogram Tasmanian devil holding that record now.

The genus Thylacinus appeared in Australia in the late Oligocene Epoch around 24 million years ago. Much like today, Australia was an isolated continent with unique forms of life and Thylacinus took up a niche similar to that of the wolves that would later thrive in Eurasia and North America. As a fairly long-lasting genus, multiple species in the genus came and went. Perhaps of particular interest was the largest of these, Thylacinus potens, known from partial cranio-dental remains found in the Northern Territory and dating to the Miocene Epoch (23.03-5.333 MYA). Projecting a reconstruction based on the proportions of thylacines from recent history, this animal would have weighed around 35 kilograms, putting it at approximately the size of a North American grey wolf, making it a formidable hunter of the increasingly arid Australian environment.

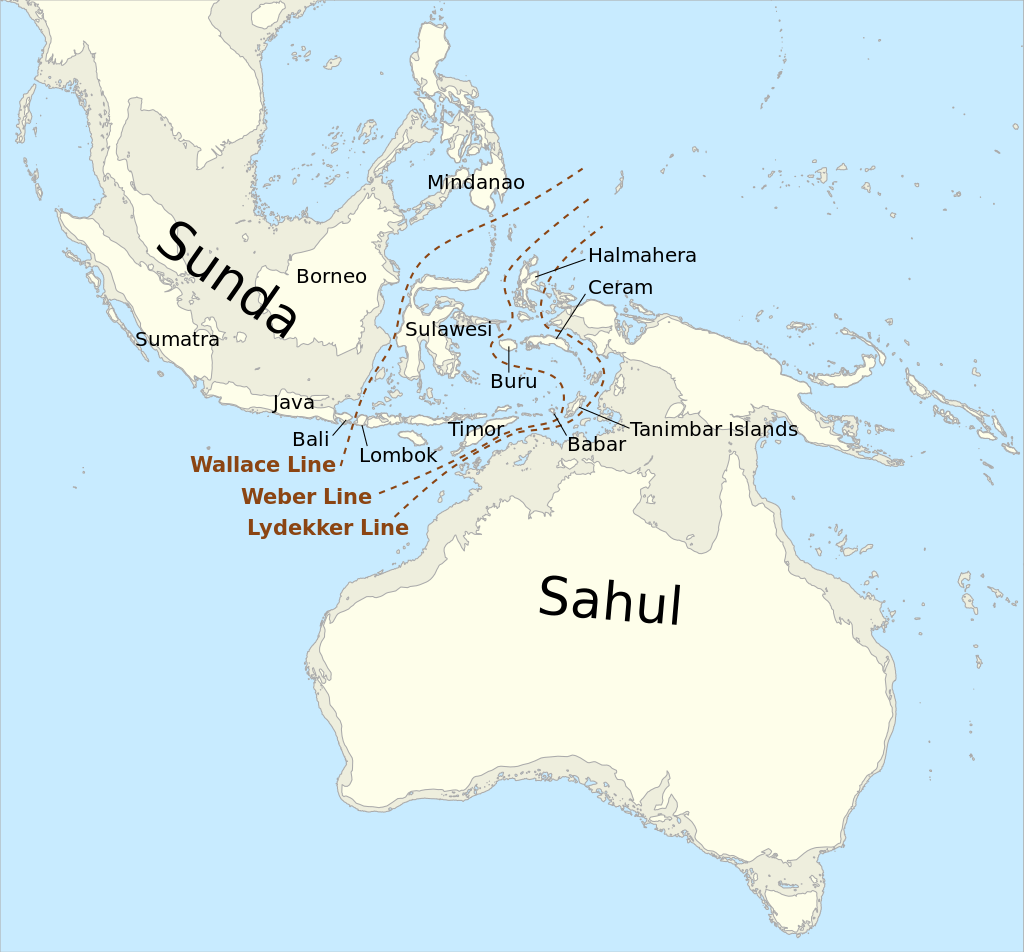

A map of what Australasia would have looked like during the Pleistocene, modeled here at a 125-meter sea-level drop by Wikimedia user Kanguole.

The thylacine of recent history, Thylacinus cynocephalus, came onto the scene at the start of the Pleistocene Epoch (2.58 MYA-11,700 years ago), the time we generally think of when we think of the “ice age.” Australia in the Pleistocene was spared the vast glaciations of the Northern Hemisphere but the amount of water locked up in the ice did have its own effect on the continent. Over the course of the cyclical advance of the ice sheets, sea levels dropped in accordance with the amount of glaciation at a particular time, maxing out at around a 150-meter drop, though generally being less than this. The result was that for most of the Pleistocene, Australia had a land connection to New Guinea and Tasmania and collectively these lands made up a single land mass called Sahul. It was across this free range that the thylacine was the largest predatory marsupial of recent memory on the continent, itself not particularly large.

A taxidermized thylacine specimen from the Natural History Museum in Vienna, shared by Wikimedia contributor GoleGole.

As we’ll discuss later, contemporary ideas of thylacine feeding habits appear to have been widely misunderstood while they were around and many ideas about them were unsubstantiated. Scientists today believe that the thylacine’s typical analogy to North American wolves is an inaccurate description of their ecological niche, preferring instead the coyote as an analogue. While not related to them at all, thylacines’ coyote-like size and features exhibit an excellent example of convergent evolution, when unrelated animals with similar survival strategies develop similar features due to shared environmental pressures. Thylacines weighed in at between 15 and 30 kilograms and stood only about 60 centimeters in height, measuring in length (including their long opossum-like tails) between 1 and 1.3 meters. They roamed relatively open habitats and were pounce-pursuit predators, able to spring out quickly at prey in an ambush or to run after it for a good distance. Thylacines weren’t regularly running down kangaroos or emus in wolf-like packs (though they may have preyed sometimes on the smaller now-extinct Tasmanian emu); instead, they were catching prey smaller than themselves such as ground birds and small mammals. Jones and Stoddart 1998 suggest that the preferred prey for thylacines would have weighed between 1 and 5 kilograms. The key mechanism for thylacines to kill their prey was their incredible jaws which simultaneously pierced and crushed unlucky animals and which could open to a whopping 80 degrees. In the Pleistocene, thylacines thrived, albeit under the shadow of far larger prehistoric Australian animals like the massive monitor lizard Varanus priscus (sometimes called by its former genus “megalania”) and the bear-sized wombat relative Diprotodon. But by 65,000 years ago, Sahul would be home to another mammal species which would ultimately come to seal the thylacine’s fate.

Thylacines and the First Australians

Madjedbebe is a rock shelter in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory which has been instrumental in developing our understanding of the peopling of Australia. Recently, continued excavation at this site has pushed human habitation there back to 65,000 years ago as evidenced by various stone tools, grindstones, and ochres used for paints or dyes. Sahul was peopled from the northwest as a relatively rapid eastern dispersal of Homo sapiens starting around 70,000 years ago moved across the Asian rim of the Indian Ocean from East Africa, a model which is called the Southern Dispersal Hypothesis. The coming of the ancestors of modern Australian Aboriginals would change the continent’s ecology dramatically but also bring the first cultural representations of its various creatures, some of which can still be found there and some which cannot be.

Aboriginal rock painting of a thylacine from Ubirr in the Northern Territory, as shared by Wikimedia contributor nettispaghetti.

For tens of thousands of years, all across Australia, both despite and expressing their astounding cultural diversity, Aboriginal people have been depicting the animals around them in rock art. Many rock art locations demonstrate reuse and additions over tens of thousands of years with modern indigenous people still visiting locations decorated in the Pleistocene and telling stories about the art there. While it’s impossible to assess across such vast stretches of time if the art had the same meaning to its creators as it does now to their descendants, there is still much to be learned about how these ancient Australians observed the world around them and expressed it. Thylacines feature in rock art on the Australian mainland from more than 2,000 years ago, as they became extinct outside of Tasmania sometime before that (with the end of the Pleistocene around 11,700 years ago, Tasmania would remain an isolated island). Normally with extinct animals, there is a certain degree of uncertainty in identifying them in prehistoric art as it is possible that reconstructions of them today differ a little bit from what ancient people saw in life but the thylacine is an exception to this due to how recently it died out and they can be identified with confidence in rock art due to their shape and their distinctive stripe pattern. At Wollemi National Park in New South Wales in a cave used still today by the Wiradjuri and Darkinjung peoples, there exists one such depiction of that striped quadrupedal form, grouped together with some quolls and wallabies, though unclear dating has raised concerns that considering it a contemporary drawing of a thylacine might be unlikely, as it may date to as recently as around 400 AD. In Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory however, many works of art can be found of thylacines which go back much older. At Djuliiri, a site still overseen by Maung people, for instance, two overlapping thylacines appear in a cave, both roughly life-sized and running side-by-side. Interestingly, they have differently shaped heads and other varying stylistic features that suggest that one might be one person’s artwork and the other belonging to someone else who decided to add to it, something which often happens at rock art sites used for a long period of time. Based primarily on stylistic developments in relation to other sites, this artwork is believed to be somewhere between 13,000 and 10,000 years old, putting it around the boundary between the Pleistocene and Holocene.

Fans of Pleistocene megafauna may have noticed that thylacines continued to survive and thrive on the mainland long after the extinctions of many of the major megafauna that prehistoric Australia is famous for (including those I mentioned: Varanus priscus at 50,000 years ago and Diprotodon at 40,000 years ago). The causes for these extinctions are disputed but it seems the end of the thylacines there was not part of this process, happening tens of thousands of years later. It has been suggested that two major developments in the human sphere may have harmed our striped friends: intensification of the Aboriginal economy (as societies became larger, more complex, and utilized more comprehensive land management technologies) and the dingo (which, apparently, defies my love of scientific names by being debated by scientists as either simply a type of the domestic dog Canis familiaris or a separate lineage from others known as Canis lupus dingo). Around 3,500 years ago, these two developments were both in effect. A major increase in Aboriginal tool technologies and the use of finer tools coincides with the proliferation of the Pama-Nyungan languages across much of the continent, bringing to mind comparisons with the Indo-European and Bantu expansions in other parts of the world. Australia had no native dogs and so the appearance of the dingo around this time likely relates to human contact with maritime Southeast Asia and the dogs people had there. Going feral and becoming effective wild carnivores in their own right, dingoes effectively pushed into the ecological niche of the thylacines and better existed alongside the growing human presence. Dingoes also had a size advantage on the mainland (there is some evidence that mainland thylacines were actually smaller than the more recent Tasmanian ones) and may have attacked and killed thylacines directly, especially as dingoes hunted in coordinated packs while thylacines did not. Separated by a strait from the mainland, the thylacine populations on Tasmania were spared the onslaught as many of the same cultural developments did not occur there and the dingo was never introduced. The result was that in the last few thousand years, our protagonists became animals of Tasmania and not of Australia at large, their fate thereafter tied to that little island.

Subjects of Science

The historical record is ambiguous on when Europeans first encountered thylacines. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman, whom the island is today named after, first arrived there on November 24, 1642. The Dutch had been the first Europeans to find Australia with Willem Janszoon’s happening upon Queensland in 1606 and the VOC (Dutch East India Company) was interested in learning what else was in the neighborhood of the East Indies for economic purposes, which did not necessarily always include taking painstaking biological notes. In many online spaces I came across while researching for this article, Tasman was attributed the first European observation of a thylacine due to his noting a scary tiger-like footprint found on the island and it appears that tacking this onto the discovery of the thylacine has been an important part of mythologizing it in the niche world of thylacine interest. Some commentators have pointed out the issue with this in that the association of thylacines and tigers comes from the color of the coat and that their footprints are not similar at all, thylacine prints being somewhat dog-like and lacking visible claws or other intimidating features. They suggest the footprints of the harmless wombat, with its big claws for digging, as a more likely explanation for what Tasman saw.

Dutch, French, and British explorers would come to the island over the next two centuries and there are a few probable references to thylacines but it is sometimes difficult to tell. 1803 was the year Tasmania changed forever as the British Empire established its first small colony at Port Arthur, on a small island off the southeast coast of Tasmania not far from the modern state capital of Hobart. In 1830, the site became part of the British penal system in Australia with the establishment of a small timber station, later expanding with other features before opening a full separate prison in 1848. From 1805 onwards, colonists had unambiguous sightings of thylacines though they appear to have not been very frequent occurrences, owing to the small number of colonists and the small number of thylacines relative to prey animals in the landscape. A couple were shot by settlers and George Harris described two of these in 1808 when the first scientific description of the species was put forth, a live specimen not being captured for science until 1820.

A scientific illustration of a thylacine by George Harris from 1808, the oldest known non-indigenous art of the animal today. It is labeled with the scientific name Didelphis cynocephala, which Harris put it in grouping the thylacine in the same genus as North American opossums but which it was moved out of to the current description of Thylacinus cynocephalus the same year.

Afficionados of art history are familiar with analyzing artworks for how the subjects of the works are depicted as a lens into the ideological framing of the artist. What has often been less analyzed is scientific depictions as art in this context. Depictions of animals have long been a window into how people have seen those animals or the natural world at large and the thylacine provides an interesting example of this. As it was first described, the thylacine tended to be portrayed by collectors and the like with an air of innocence, especially as the animal was not particularly large and not a danger to humans, even being timid and largely avoiding them. Popular depictions, however, tended to move towards its portrayal with the same stereotypes used to portray other wild predators, most notably wolves, tigers, and hyenas, all of which the animal was variously called, often simply with the word “Tasmanian” attached to the front, despite all of these animals being considerably larger than thylacines and being wholly biologically unrelated, something recognized as early as the first scientific descriptions. Unfortunately two major streams would impact the ultimate fate of the thylacine: the thylacine as an object of exoticism and the thylacine as a threatening predator. The first would make it a favorite of trophy hunters and the second would make it a livestock pest to be exterminated.

While we are in the early 1800s, it is probably worth acknowledging what else was going on in Tasmania. After all, the thylacines were known by others besides the Europeans in this period. Unfortunately, these others were treated by Europeans, like the thylacines, as part of the landscape to conquer. Estimates vary on the number of Aboriginal people living on Tasmania when the British set up the Port Arthur settlement in 1803 but it is placed somewhere between 4,000 and 15,000. By 1835, there were less than 400 “full-descent” Aboriginal Tasmanians. The exact historical processes of the Tasmanian genocide (including the designation of the period as a genocide) is controversial both in Australian politics and academia. Whatever the case, European presence significantly negatively affected those who were already living in Tasmania such that the population fell to near extinction. Treating this topic properly would require much more time and many more words than I can give it here but I feel comfortable in saying based on what I have read that this period does constitute a rather unambiguous genocide and that attempts to scrub it of that label are in favor of less than respectable interests and viewpoints. In short, sporadic violence between settlers and indigenous people occurred from the beginnings of Port Arthur but following indigenous resistance to the encroaching colony ramping up in 1824, the colony declared martial law in 1828 and a guerilla conflict ensued which saw far higher casualties for indigenous people than colonists and which was accompanied by the disruption of indigenous economies and deadly disease outbreaks. Following the conclusion of the conflict which became known as the Black War in 1832, an attempt was made to deport all indigenous Tasmanians to the mainland with only a few managing to evade the deportations over the next few years. Tasmania was ethnically cleansed. Today the descendants of these indigenous Tasmanians struggle to recuperate their heritage, which has to be reconstructed heavily from what fragments remain from different people groups.

Amidst this grand catastrophe playing out across the island, thylacines were increasingly shot. And a new animal became increasingly present on the island: Ovis aries, the domestic sheep. Sheep thrived in Tasmania and they soon became a fixture of the Tasmanian landscape, helping to generate monetary wealth for the increasingly diversifying colony with wool as an exportable good. Taxidermies and drawings of thylacines loved to give them pouncing and snarling wolf-like postures and by the mid-to-late 1800s, the thylacine was more or less publicly viewed as the local form of the wolf. Just as pastoralists killing wolves has been a disaster for their populations in Europe, America, and elsewhere, so would a similar phenomenon occur for the thylacine. But some key differences were at play: island populations are more fragile than large continental populations and thylacines did not prey on sheep to any significant degree. Regardless, stereotypes turned the thylacine from an exotic curiosity into a maligned pest. Having crushed the island’s indigenous peoples, the new order in Tasmania would now turn its sights on the animal that several millennia before had made the little island its last refuge and the countdown ticked quietly closer to extinction.

Murder

In 1924, the Van Diemen’s Land Company was established to invest in Tasmania, Van Diemen’s Land being the name the British Empire designated Tasmania with before 1855. Under the leadership of sheep farming expert Edward Curr, they were the major impetus behind the expansion of the industry on the island and by 1830, there were a million sheep there as opposed to the 2,000 to 4,000 thylacines that lived there prior to colonization. The reality however was that the sheep industry taking off here happened in spite of the situation being unideal and not necessarily because it was the best place. Soil often did not grow the right grasses and other plants to feed sheep and so not all terrain on the island was great for keeping them. Many colonists also were simply inexperienced and did a poor job of managing their sheep while others took to bushranging and raided herds. Sometimes there was little to stop a swagman from grabbing a jolly jumbuck and shoving it in his tucker bag to come waltzing matilda with him. Shipments of necessary supplies from the larger penal colony of Sydney could be unreliable at times. Amidst all of this, thousands of sheep annually died in cold winters or starved to death while predators picked off the occasional one. The Tasmanian devil seems to have been a notable culprit here, often attacking animals its size and larger. Thylacines were around though and their wolf-like appearance made them frequent targets of blame and the colony and company’s misfortunes with the sheep industry could often be shifted onto this elusive predator somewhere out there. Two thylacine attacks on sheep in 1817 and one in 1823 were the only ones ever verified by the VDL company.

In April 1830, the company put out a bounty for turning in killed thylacines which initially increased per thylacine killed but was soon after revised to a fixed rate of ten shillings a thylacine. Company management of course likely knew that the thylacines weren’t a real problem but amidst highly publicized losses needed to look effective in doing something about it. The result was bloodlust: colonists began shooting thylacines on sight for the prize money and the massacre began. The increasing image of the animal as a pest that needed to be controlled meant that many were killed with no particular interest in the money as well. Through the middle of the 1800s, Tasmania continued to develop into a proper colony with a diversity of industries and from 1856 it had its own parliament, representing a transition from a mere penal operation and company enterprise to a centralized part of the British Empire. Fans of Australian history will likely be aware that in much of the late 1800s, a wealthy land-owning class dominated colonial politics often at the expense of the poorer working frontier class who were descended from transported criminals. Tasmania was similar to the mainland in this regard and wealthy interests dominated the parliament. Naturally this meant that many mindsets from the company carried over, including regarding the thylacine, where the question of instituting a government bounty hung in the air.

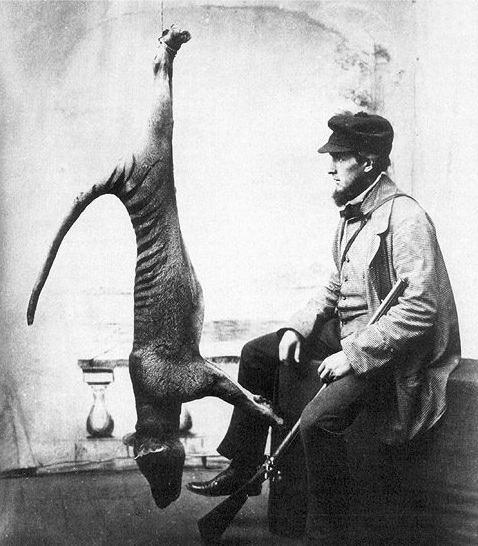

A hunted thylacine, photographed in 1869.

On November 4, 1886, the decision that would kill a species was made in the Tasmanian parliament on a close vote of 12 for and 11 against. A bounty system would be adopted at the official level with 1 pound paid per adult and 10 shillings for younger animals. It officially came into effect in 1888 and would last until 1909. In those 21 years, the government would pay bounties on some 2,184 individuals, a number that was effectively extermination for a small island population already affected by habitat loss and previous culling efforts. Before this started and while it went on, between 1878 and 1893, records show that 3,482 thylacine skins were exported to Britain for turning into coats and other luxury items. The bounties became so sought after that control measures had to be put in place against fraud: toes and ears were cut off to mark turned-in thylacines as having been paid for so that the hunter could not then simply take them to another place to report them again. Disease killed many thylacines too it seems based on evidence from captured specimens but the nature of this was poorly studied and so is hard to comment on.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, a new sort of institution was taking prominence both in the study of the natural world and in public spectacle: zoos. In the 1880s while the government-sponsored extermination campaign began, a separate sentiment existed that was more friendly to the thylacine, albeit as an exotic and increasingly elusive product of interest. If you could capture a thylacine live and transport it overseas to a major zoo, you might make many times over the amount of money gained from killing one. Zoo guests wanted a rare chance to see the strange animal and it might be a good boost to admissions income. In 1910, London Zoo for instance paid 28 pounds a piece for two thylacines. Even if this was driven by interest and excitement towards the animal, it was effectively just another force feeding off of a rapidly decreasing population, especially as captive breeding programs were unsuccessful. Transportation was not pretty good on the animals and in one load of 25 to London, for instance, 5 died in transit and another days after arrival.

By 1909, the thylacine population had dropped dramatically and voices of concern had been heard. The bounty system ended but now the animals were exceptionally rare and still often seen as pests by keepers of sheep, chickens, and other animals who kept shooting. Zoos which had rushed to get ahold of them were not effectively keeping them as the specimens weren’t breeding and only lived so long. On May 13, 1930, one Wilf Batty killed a thylacine at his father’s farm in Mawbanna and took a photo with it, achieving the uncomfortable distinction in retrospect of being the last person to unambiguously document a thylacine in the wild. Sightings continued to be reported after this and there are still true believers who claim some small hidden number exists today, but as far as science is concerned, no new veritable data came in after this.

Wilf Batty with the last thylacine to be shot in the wild in 1930.

The last thylacines were those in zoos. London Zoo’s last specimen died out in 1931, ending the era of the popularity of thylacines in international zoos and leaving just the few that lived in Australia. Hobart Zoo, having been founded in 1921, would become the last home to thylacines known to exist. The zoo was not large with only 78 cages and three full-time keepers (which reduced to one in 1935 amidst the difficulties of the Great Depression). Staff dealt with the most dangerous placental carnivores while most other animals were cared for by part-time volunteers. Sadly, the sorry state of the zoo means that the last thylacines spent their final days often inconsistently fed and with a cage that might go some time uncleaned. The zoo was run by one Alison Reid who had an unpaid position where she was allowed to live at the zoo and manage things but the zoo itself was technically owned by the city. Arbitrary rules often made it hard for her to properly address issues, as she was not even allowed the zoo keys. In 1936, the second-to-last remaining known thylacine in the world was not only frequently unfed but often left locked out of its sleeping quarters for 24 hours at a time. It would have coughing fits and despite Alison Reid’s interest in responding, her lack of keys often prevented her from doing much. Some famous photos were taken of this thylacine in this time and in fact if you see pictures of the “last known thylacine” online, they are likely this second-to-last specimen, which was a male. The photos also show an emaciated and malnourished animal. Within days of the famous photographs taken, it died, but in a horrible detail of the story, the date of its death is not record (sometime between May 12 to 19, 1936) because rather than informing about the discovery of the dead animal properly, workers had simply found the dead thylacine and thrown it in the zoo’s refuse pile, where it was found afterwards already partially decayed, ruining one of the last possible scientific specimens. Another thylacine, a female, supposedly caught by a trapper, was delivered to the zoo on May 20, 1936 and paid for by the zoo for a mere 5 pounds. Similar maltreatment followed and the animal died mere months later on the night of September 7, 1936. Thus quietly in her sleep, she moved on from the world of the living and the number of animal species in the world decreased by one.

The second-to-last known thylacine, malnourished and sickly in the abusive Hobart Zoo, days or less before its death in 1936, taken by Benjamin Shepherd.

Afterlife

The body of the last thylacine was dutifully taken to the Tasmanian Museum where she was turned into a specimen through the preservation of her skin and skeleton. Interestingly, these went misplaced for most history since then, only being rediscovered and redescribed scientifically in 2023. After the last thylacine’s death, the zoo actually promised to pay 40 pounds for another one, which was met with outrage by social activists. One, Edith Waterworth, wrote in the Hobart Mercury of March 9, 1937, referring at the same time to the recent thylacine deaths and to any hypothetical newly acquired individuals, “I have seen one animal come in from the bush… After the frenzy has died down, it will pace up and down, its whole body expressing the devastating misery it feels… The frozen despair which its face and its whole body expressed would wring the heart of any person… Its frenzy was over, it had refused to eat… and in the course of time it will die.” The zoo failed to continue following monetary problems and scandal and closed on November 25, 1937, not much over a year after the last thylacine had died there.

The sentiment on thylacines has changed dramatically since they died out. Once a pest and unfairly hated creature, its disappearance sparked a certain sympathy and it has become a go-to example for conservationists about the alarmingly heightened rate of extinction humankind is wreaking on the world; after all, the thylacine’s story isn’t unique so much as it is well-documented. The Tasmanian state coat-of-arms features two of them as heraldic animals and depictions of them are now almost always positive and mournful. Meanwhile, a cryptozoological interest in the creature also continues to suggest that some might still be out there, but no good evidence for this has really materialized, though a minority of researchers hold the view that the animal did potentially survive for decades in the wild after the Hobart Zoo deaths. The State of Tasmania did not move the thylacine off its endangered species list by declaring it extinct until 1986; the animal had only become protected 54 days before the death of the last zoo individual, so during almost all of the time it was protected, there were no individuals left to protect.

As of 2018, the thylacine has, through the use of remaining specimens, joined the growing list of organisms whose DNA has been fully sequenced by scientists and is available for research and development. Some commentators have suggested that this might mean that the thylacine will make a return through the wonders of genetic engineering. This is possible but certainly not close as a possible surrogate species for a thylacine doesn’t really exist.

Whatever the case, the tale of the thylacine is one of a tragedy recorded for us, which played out on a grand scale before ending in fast-paced violence. It is a reminder that the wealth of life on this planet that we enjoy needs to be treasured and protected because it is not forever. What species will we tell this story about next?

Further Scholarly Reading:

- Allen, Jim and O’Connell, James F. “Getting from Sunda to Sahul.” Terra Australis 29 (2008): 31-46. 459300.pdf (oapen.org)

- Brook, Barry et al. “The Tasmanian Thylacine Sighting Record Database (TTSRD): 1,223 quality-rated and geo-located Thylacine observations from 1910 to 2019.” Australian Zoologist 43, 3 (2024): 419-435. document (hal.science)

- Clarkson, Chris et al. “Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago.” Nature 547 (2017): 306-310. hdl_107043.pdf (adelaide.edu.au)

- Feigin, Charles Y. et al. “Genome of the Tasmanian tiger provides insight into the evolution and demography of an extinct marsupial carnivore.” Nature: Ecology and Evolution 2 (2018): 182-192. s41559-017-0417-y.pdf (nature.com)

- Field, Julie S. et al. “The southern dispersal hypothesis and the South Asian archaeological record: Examination of dispersal routes through GIS analysis.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 26 (2007): 88-108. Field_et_al_2007_JAA_southern_dispersal_GIS_simulations-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Freeman, Carol. “Figuring Extinction: Visualizing the Thylacine in Zoological and Natural History Works 1808-1936.” BA thesis, University of Tasmania. (2005.) https://figshare.utas.edu.au/ndownloader/files/40941896

- Holmes, Branden. “Thylacines and Dingoes.” REPAD: The Recently Extinct Plants and Animals Database. Thylacines and Dingoes – The Recently Extinct Plants and Animals Database (recentlyextinctspecies.com)

- Jones, Menna E. and Stoddart, D. Michael. “Reconstruction of the predatory behaviour of the extinct marsupial thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus).” Journal of the Zoological Society of London 246 (1998): 239-246. -predatory_behaviour_thylacine-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Larsen, Brendan B. et al. “Inordinate Fondness Multiplied and Redistributed: The Number of Species on Earth and the New Pie of Life.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 92, 3 (2017): 229-265. Inordinate-Fondness-Multiplied-and-Redistributed-the-Number-of-Species-on-Earth-and-the-New-Pie-of-Life.pdf (researchgate.net)

- Letnic, Mike; Fillios, Melanie; and Crowther, Matthew S. “Could Direct Killing by Larger Dingoes Have Caused the Extinction of the Thylacine from Mainland Australia?” PLoS ONE 7, 5 (2012). Could Direct Killing by Larger Dingoes Have Caused the Extinction of the Thylacine from Mainland Australia? | PLOS ONE

- Madley, Benjamin. “From Terror to Genocide: Britain’s Tasmanian Penal Colony and Australia’s History Wars.” Journal of British Studies 47 (2008): 77-106. From_Terror_to_Genocide-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Meredith, Robert W. et al. “A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes.” Journal of Mammalian Evolution 15 (2008): 1-36. A-Phylogeny-and-Timescale-for-Marsupial-Evolution-Based-on-Sequences-for-Five-Nuclear-Genes.pdf (researchgate.net)

- Morton, Elizabeth and Tsahuridu, Eva. “Moral framing and the thylacine: a historical example of shifting frames.” Accounting History 28, 4 (2023): 550-576. 10323732231162368 (sagepub.com)

- Paddle, Robert N. and Medlock, Kathryn M. “The discovery of the remains of the last Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus).” Australian Zoologist 43, 1 (2023): 97-108. i2204-2105-43-1-97.pdf (silverchair.com)

- Port Arthur Historic Site website. History Timeline – Port Arthur Historic Site

- Prowse, Thomas A. A., et al. “No need for disease: testing extinction hypotheses for the thylacine using multi-species metamodels.” Journal of Animal Ecology 82, 2 (2013): 355-364. No need for disease: testing extinction hypotheses for the thylacine using multi‐species metamodels – Prowse – 2013 – Journal of Animal Ecology – Wiley Online Library

- Taçon, Paul S. C.; Brennan, Wayne; and Lamilami, Ronald. “Rare and Curious Thylacine Depictions from Wollemi National Park, New South Wales and Arnhem Land, Northern Australia.” Technical Reports of the Australian Museum 23 (2011): 165-174. 74918_1-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Yates, Adam M. “New craniodental remains of Thylacinus potens (Dasyuromorpha: Thylacinidae), a carnivorous marsupial from the late Miocene Alcoota Local Fauna of central Australia.” PeerJ: Life and Environment 2, e547 (2014). New craniodental remains of Thylacinus potens (Dasyuromorphia: Thylacinidae), a carnivorous marsupial from the late Miocene Alcoota Local Fauna of central Australia [PeerJ]

Living in the Longue Durée is part of the History Nerds Network, a group of friends who together make history content online. Check out our Discord server here if you’d like to chat with us: https://discord.gg/dzdrzUpKeG You can also follow for post updates on the Facebook page ( https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61559902349797 ) or on Instagram at @livinginthelongueduree .

Consider supporting my time and money investment into research on Patreon if you want to allow articles like this to maintain their quality and regularity: Living in the Longue Durée | A thoughtful and eclectic history blog. | Patreon

Leave a comment