Walking through the streets of a bustling neighborhood, you weave through a gathered crowd, wandering around and mingling, only moving aside when a cart or donkey needs passage. At the edges of the crowds, street-salespeople attempt to sell loaves of bread and fresh produce, usually getting turned away to the annoyance of those gathered but making just enough money to make a slight profit with the sales they can make. The reason for this gathered crowd is the same reason you’ve come: a business venue located through a small door surrounded by decorative frescos.

As you enter, you spy a small wooden table where your friend Quintus sits. “Salve, amice!” he greets you as you take a seat. The atmosphere is boisterous with men and women communicating about life and business while the family that owns the place and their employees move about serving food in exchange for coin. A female worker passes by and some young man at a nearby table catcalls. She stops by your table and gestures to the array of foods available: a pile of breads fresh from the local baker, hanging meats (the shape of cooked pig stands out the most, but is accompanied by poultry) and cheeses. Wine flows a-plenty though rumor has it that some of it is watered-down at this location. You order a fine meal of pork, olives, bread, and wine, which will be served for your greasy hands soon.

The crowd around you is a microcosm of your neighborhood and most faces are those you’ve seen before: the urban poor and middle-classes. Here in Rome in the first century AD, the most significant politics in the world take place in buildings far grander than this one but here you are in the arena of the politics of the local. As the lady walks away, the catcaller is himself called out to by another man sitting at yet another table. He yells that she won’t be seeing such a disreputable young man tonight. Chairs are pushed back and two men stand up and soon the small establishment is the scene of a fistfight to mixed response from the crowd.

Food and Economy in the Roman Empire

Triclinium reconstruction from the Archäologische Staatssammlung München as shared by Wikimedia user Mattes.

When we think of eating in ancient Rome, we tend to think of the triclinium, the fancy form of dining room that Hollywood so loves to display, in which three beds are placed surrounding three of four sides of a central table, where host family and guests recline to eat from the banquet on the center table while slaves prepare and serve food. Perhaps intuitively of course, this form of dining was not something that most Romans did and was a way for the wealthy to display prestige to one another. It is represented so frequently in large part because the opulence of the upper class of Roman society has become such a media staple and this same class is the one which primarily produced our most influential historical records. This raises the question: how did communal eating happen among other portions of the Roman populace? Today, we will be looking at the urban lower and middle classes of first few centuries AD in the core of the Roman Empire, primarily Italy. It’s important to realize that yet other conditions would have existed in the rural areas as well as across the culturally diverse communities from Britannia to Arabia. The writers we will be using as sources use primarily Latin (distinguishing them from those more local to the Hellenized east) and the archaeology we will use as reference points comes primarily from Italy, especially Pompeii and Herculaneum, located in modern Naples and destroyed (but also thus archaeologically preserved) by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Food is, throughout the history of the human species, perhaps the most significant factor in determining the direction and structure of societies. Populations rise and fall by available calories and calorie availability is impacted by agricultural productivity and the subsequent distribution. In ecology, environments are said to have carrying capacities, the amount of individuals in a population that can be said to be supported by some area before resource stress prevents further growth. Agriculture modifies land in such a way as to increase its carrying capacity through the replacing of potentially inedible organisms with a large amount of edible ones. Cities are enabled by the surplus created by agriculturalists which can be transported to institutions for redistribution, supporting a large population in a dense area. This was true when the first cities developed in Mesopotamia six millennia ago, it was true in the Roman Empire, and it is true today. Getting food into a city from the farms is one process but another is moving it to the areas of the city where it can be reasonably acquired by inhabitants without them having to go so out of the way that it will otherwise hinder their daily activities. Modern cities have grocery stores and restaurants which are placed so as to profitably service portions of the population, taking into the context and balancing the concerns of avoiding too much competition while also being close to where the traffic is. City-planners play a role too in ensuring that transportation infrastructure enables access to these food depots. The failure of business owners or city-planners to service these needs can lead to food deserts that compound the issues of urban poverty.

In the Roman Empire, these same concerns affected urban layouts and the responses of both private owners and the state, but technological differences modulated the demands. Morley (2011) estimates (in the middle-count of several models) that the urban population of the city of Rome at the height of the Empire was around 1,000,000 people and Italy as a whole had about 6,000,000 with around 30% of the population of Italy living in urban settlements. Thus compared to the rest of the classical world, Rome was utterly massive and presented challenges of scale as-yet unseen in the history of cities. (For comparison, the second largest city in the Roman Empire at this time, Alexandria in Egypt, peaked at around 600,000 people at most.) And secondly, this means that by classical standards, the region was heavily urbanized outside of the capital as well. A higher amount of people in cities means a higher amount of people who need the relevant industries that allow for taking the agricultural goods there from the countryside. Essentially all urban traffic in this period is on foot or occasionally pack animal so the fundamentals of daily existence must be within a comfortable walking distance. Humans walk about 80 meters (about 262 feet) in one minute according to a standard used among modern Japanese city planners. If we imagine that people want short walks for daily necessities in under 10 minutes, businesses serving these needs thus must be within 800 meters (about 2,625 feet) of where people are living or working. Those working outside of the food industries would need to go to shops, bakeries, ambulatory vendors, or the restaurant-like establishments that are the subject of this article to acquire food. It is worth noting as well that due to the small insulae (something like apartments) that many less wealthy Romans lived in, access to a suitable kitchen was not really part of every household and this increased the importance of communal culinary spaces. (Nappo (1997) notes that many small houses in Pompeii have a tiny room that functioned as both kitchen and latrine!)

So let’s finally discuss the titular “restaurants.” This is somewhat of an imprecise term on my part. The scholarly literature that I’m reviewing in writing this has many vocabulary preferences here, such as “bars” and “taverns.” The Romans themselves called them popinae, tabernae, cauponae, and thermopolia among other things. While some have tried to find specific distinctions between these labels, it’s generally been concluded that precise definitions were fluid and overlapped and for our purposes, we’ll treat them mostly the same here. In general however, a taberna or popina was more likely to also offer lodging while a caupona would not and the term thermopolium is known to us from a single use by Plautus, a Roman playwright who lived between around 254 and 184 BC. This last term, which is clearly derived from Greek, is therefore potentially older and less common, despite being common in pop-coverage of Roman urbanism topics. In written sources and art, we have many descriptions and depictions of these types of businesses, which were privately owned and run. And it is from the archaeological record of two doomed cities that we get our best material evidence. But before we get there, let’s take an aside to describe the Roman diet.

A Good Roman Meal

Mosaic from the 100s AD near the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome as shared by Wikimedia user Jastrow.

Agriculture was, by far with nothing even close, the largest and most significant industry and activity of the Roman world. The crops that were the staples of the classical Mediterranean were those which had been domesticated in the Near-Eastern neolithic and principle among these were the cereal grains. Everyone ate bread, which could be made of wheat (specifically emmer, Triticum dicoccum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) and which was often readily available from the many bakeries that dotted Roman cities. Grain was also a staple of social welfare policies with the Cura Annonae being a system within the capital where free grain (or bread) was distributed to the citizens, some 200,000 at the city’s height (a fifth of the population) receiving subsidized grain from this program. It was widely understood (and criticized) that the grain dole helped placate what might otherwise be an unwieldy number of unhappy people, hence why the poet Juvenal writing around 100 AD in his Satire X penned the famous phrase “bread and circuses” for what the people wanted out of their leadership.

Orthographic projection of the Roman Empire at its territorial height in 117 AD on a globe from Wikimedia.

Reading about the economy of the Roman Empire is always a practice in discovering surprising amounts of modern parallels for a premodern civilization. Among these is the availability of produce grown in one climate zone in vastly different parts of the Empire. At the Empire’s height, the northernmost Roman territory was in Britannia where the Antonine Wall (at the modern boundary between England and Scotland) at around 56 degrees north was at a similar latitude to modern Moscow and the southern part of Hudson Bay in Canada. The southernmost reach of the Empire was down the Nile River in Egypt, above 22 degrees north at what is now Maharraqa in Nubia, where a garrison was kept against the Nubian kingdom of Meroë. Today, the 22nd degree north is the treaty line recognized for most of the border between Egypt and Sudan, runs just south of Hong Kong, and crosses the Hawaiian island of Kauai. Across these 34 degrees of latitude, the Roman Empire had a vastly diverse ecology and different crops grew well in different places and the same systems of road and sea transport that allowed armies and messages to move so effectively created the means by which various delicious things could be enjoyed in distant provinces from where they were grown. Archaeobotanical remains in Britain for instance demonstrate that local Romans had access to such things as figs, olives, and even peaches, all of which aren’t exactly built for the climate of northern Europe. Romans enjoyed many vegetables, nuts, and fruits from apples to almonds to grapes to celery. It goes without saying that two of the most prized fruits were olives and grapes which were both consumed by themselves and used to produce olive oil and wine, which were indispensable parts of Roman cultural identity.

It’s an often repeated idea that meat was not something that most people ate in the classical world and that it was almost exclusively the wealthy who consumed animals. While meat consumption on average was probably lower than for most people in developed countries today, the idea that it wasn’t a significant part of commoners’ diets is demonstrated to be fairly inaccurate by the ample butchered bone remains that can be found around settlement sites throughout the Mediterranean. The class divide was less about whether people ate meat but rather which meats they ate, which might also have ethnic and cultural dimension, as in Judea for instance. Pigs in particular were a staple and pork was something the Romans brought more of a demand for where they went. The rise in pig presence in the Hellenistic and Roman periods in Judea has even led to the suggestion that Jewish farmers may have raised pigs to sell to Greco-Roman consumers! Whatever the case, in the social eating spaces of the Roman world, pigs were certainly the most prominent animal to get together and feast around. Aside from these, there were sheep, goats, and cattle, though these were generally more used for secondary products rather than meat. Keep in mind with large animals that a lack of refrigeration meant that slaughtering one for meat had to be justified by the presence of a group of people capable of eating everything there within a day or two and that it would mean loss of future production of products like wool or milk as well as pulling ploughs or carrying packs. Dairy was a major concern here as cheese was a frequent inclusion in the Roman diet.

The European edible dormouse (Glis glis) on left in a photo by Bouke ten Cate and the hazel dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius) on right in a photo by Danielle Schwarz. Both images are taken from Wikimedia and are absurdly adorable pictures of something the Romans used to make meals out of.

I could have a whole article on Roman impacts on the environment but one of the most fun and relevant details here is how the Roman Empire is associated with the rapid proliferation, intentionally and unintentionally, of certain types of dormouse. The European edible dormouse (Glis glis) and the hazel dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius) were both considered delicacies in the Roman world and they were raised within specialized jars called gliraria with lots of tiny air holes inside. Aside from raising them in captivity though, the facilitated expansion of fruit trees from the Near East that the Romans (and before them other colonizing Mediterranean peoples such as the Phoenicians) used for food actually extended the range of dormice in the wild as their feeding conditions got better on the tail of walnut, hazel, almond, fig, cherry, peach, apricot, and medlar. Dormice today are a significant agricultural pest in Europe partly because of a massive ecological shift driven by the classical food economy! Similarly, just as urbanization today drives the expansion of environments in which certain rodents thrive, the rapid growth of Roman cities, towns, farms, and more provided plenty of new shelters for these animals to inhabit. Within the caupona that was the subject of the opening of this article, it would likely not be rare at all to see rodents scurrying across the open floors, taking advantage of the amount of nutrition to be found in such a place. But as for the more intentional use of dormice, how did Romans eat them? Writing sometime in the first century AD (likely in the reign of Tiberius, between 14 and 37 AD), Marcus Gavicus Apicius (more on him below) reports that dormice had become luxury prestige dishes for the upper class and were served with garum, pepper, and pine nuts and stuffed with both pork and their own entrails. His younger contemporary Petronius in his novel Satyricon includes a scene in which dormice are feasted on with honey and poppyseeds. Most likely, in our lower and middle class eating spaces, this sort of prestige food was hardly present but writings about rich Romans showing off how fat their stuffed dormice were leads me to think about to what extent from time to time this sort of thing would be in some way emulated down the social ladder, especially as the animals were so clearly thriving in the wider world around them.

In the last paragraph, I briefly mentioned garum. What is that? Naturally, as a people who built their empire around a sea, the Romans consumed a lot of seafood and there was a significant Mediterranean fishing economy. Near coastlines, fish would have been a dietary staple and as one went inland, due to the limits of a world with only salt instead of refrigeration, it would have crawled gradually towards a more high-class food. But another use for fish in the ancient Mediterranean world (and while the Romans are famous for it, predating them immensely) was fermenting them to produce a liquid that could be used as a condiment, which in Latin was called garum, a word derived from Greek. As it was easy to transport and easy to produce so long as fish was present, garum transcended all Roman social classes as a popular flavor. Our opening caupona would have certainly made good use of it. Aside from garum, the most significant flavor additive in the Roman world was salt, which was a high-value but often necessary good because of its other purpose as a preservative for foods, especially meats, in transport. Salt was energetically intensive to produce as it had to be boiled out of seawater and consequently it could be incredibly expensive at times.

Above I mentioned Marcus Gavius Apicius, a notable writer on the culinary arts from the first century AD. In truth we know nothing about this man or even if his work was pseudonymous. But regardless, his work De Re Coquinaria or “Of the Things of the Kitchen” has become the most well known primary written source on Roman food culture both for academics and popular enthusiasts. In my sources at the bottom of this article, you will find included both the full Latin version of this work and an English translation with commentary. It is often presented in the Roman history spaces I inhabit online as “a Roman cookbook.” It is that in part but also is concerned with things such as the preparation and storing of kitchen resources. Much of it will be familiar to a modern cook while much of it shows how things have changed with time. If you feel so inclined to use the recipes contained therein, you can reach out on the social media pages included at the end of this article and tell me how it went. We now return to the topic of venue.

The Venue

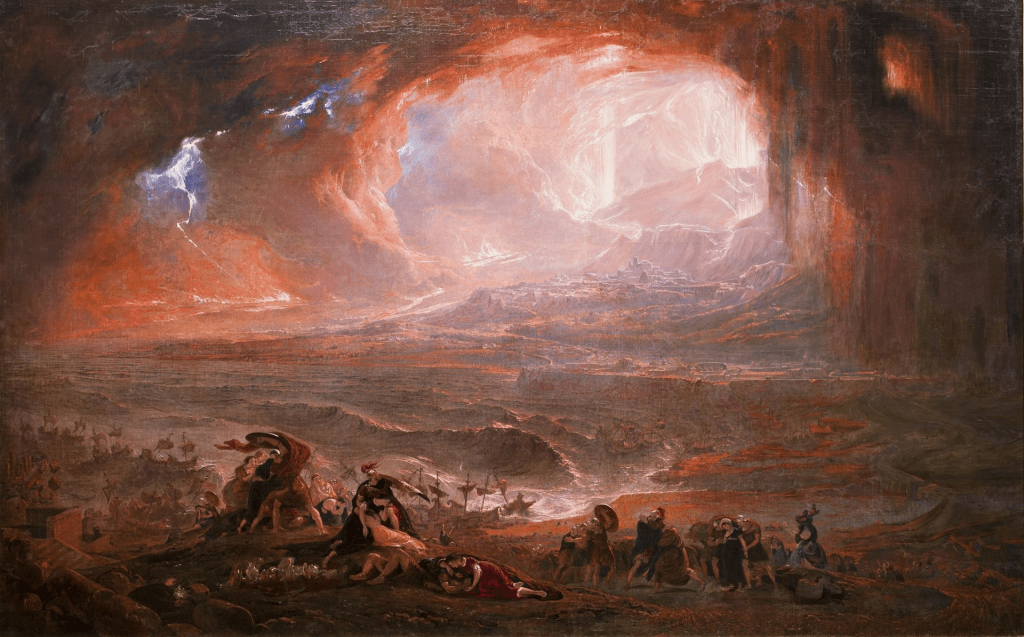

British artist John Martin produced The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 1822. It displays his signature style of dramatic huge environments that dwarf individuals and, despite being far from a contemporary source, captures the gravity of what happened better than any other portrayal I’ve ever seen.

In 79 AD, Pompeii and Herculaneum were two cities on the Bay of Naples, overshadowed by the massive Mount Vesuvius. And then they weren’t. In perhaps history’s most famous volcanic eruption, putting out 100,000 times the energy output of the Hiroshima bomb, the cities were buried by a fast-moving pyroclastic flow that superheated the inhabitants who had not yet fled and buried the cities in a new addition to the local geological column that happened overnight. 1,500 victims from this horrific event have been identified in the archaeological record but the actual casualty count could have been more than 10 times that. Regardless of this utter destruction, two entire cities became pristinely preserved for future archaeology and our knowledge about the built environments of the Roman world is disproportionately informed by the information the situation has left us with.

The interior of a caupona at Herculaneum, as uploaded to Wikimedia by user Jebulon.

Pompeii and Herculaneum had many social eating places and a general format can be described for how they were built. Generally, they opened directly to the street with an entrance that could be shuttered during closing hours, like many small urban shops around the world today. This would also have allowed these eateries and bars to push their way into the street itself and set up for interior and exterior gatherings and activities, pulling everything back in when it was time to close down. In fact, in the first century AD, the poet Marcus Valerius Martialis, who tended to focus his topics on daily lived realities, complained that a popina had expanded too far and taken over a street. Echoes of this sentiment can be found today in the local complaints of trendy eating cities like New York and Paris where how much eateries can use the sidewalks and roads out front is a subject of both local dispute and public celebration. It is unclear the extent to which the street-facing parts of the building were decorated but it is suspected that frescoes may have been a notable part of this. Graffiti, as the remains of these same cities from the eruptions have shown us plenty of examples of, would also have been highly common. (In one location in Herculaneum, someone drew a picture of a penis and wrote “handle with care!” I could go at significant length highlighting examples of this form of self-expression but plenty of posts have been written on that.)

Bar scenes from frescoes in Pompeii.

On the interior of the shops, it was common to have an L- or U-shaped counter with a series of depressions in it (possibly for storing hot food for serving up). The counter was likely what the staff of the establishments largely worked behind and the areas behind them tend to come with a cooking surface, a spot for heating water, and a chimney for letting out the smoke that the fires for these things would have generated. Large collections of amphorae demonstrate the scale of the food economy and the storage of necessary goods and ingredients such as olive oil while coins provide an example of what moved through the locations as a medium of exchange. These venues were privately owned and managed by families which included male and female workers. Some of the larger ones featured additional rooms which had their own tables and chairs and sometimes even triclinia made of bricks where the not-so-rich could still have the sort of formal meal setting that befit important business. Interior decoration could include painted frescoes like the ones above, which show the exact sorts of activities one would expect in the same space, a celebration of present experiences. They also let us know that the spaces were associated with gambling and other gaming, as well as business dealing. Written sources add sexual services to the list of things one might find in one of these spaces and a Pompeii graffito boasts on behalf of its writer for banging a barmaid.

For the wealthy, these establishments were generally seen as beneath them and they mostly have negative things to say, despite evidence pointing to them being a very central part of local life. Of the 158 such establishments identified in Pompeii by archaeologists, they tend to be concentrated on the major roads and their intersections as well as near city gates where they could take advantage of those coming in and out of the city, true mingling locations for vast swathes of society. Aside from associations with the seedy parts of urban culture, it was perhaps just wanting to separate themselves from the masses that made elites dislike these places more than anything else. Horace complained about the people there being greasy, Ammianus Marcellinus complained that the people there snorted through their noses while gambling and bantering about the chariot races, and Juvenal describes an Ostia popina as being frequented by everyone from thieves to runaway slaves to a priest of Cybele (a goddess from Phrygia in modern Turkey who had become a popular foreign import deity, her cult made all the more controversial by the gender-bending of her clergy). To an extent, all these things were probably true. As some of the most public spaces of urban life, they would have been the site of a sort of unfiltered representation of the local and everything that came with that. But as with all questions of the premodern world, we can’t pretend that texts can give us the whole picture by themselves and we can perhaps redeem these spaces a bit by recognizing that they were often the lifeblood of communities via food access and that the activities that took place in them meant a lot of different things to a lot of different people, most of whom were not these outside observers who owned private triclinia.

The social and economic world that these businesses were part of was a dynamic one, different from our own and yet almost intimately familiar. When imagining how urban Romans ate, we need to remember the exciting culinary world they built as a civilization, the demands that emerge from the conditions of urban life, and how structures and built space relate to culture. Somewhere at the crux of a web of all these topics is the truth of the Roman restaurant experience. And I think for all the issues this world had to offer, there is something grounding in imagining that.

Further Scholarly Reading:

- Apicius, Marcus Gavius, De Re Coquinaria, first century AD. 0350-0450,_Apicius._Marcus_Gavius,_De_Re_Coquinaria,_LT.pdf

- Carpaneto, Giuseppe and Cristaldo, Mauro. “Dormice and Man: A Review of Past and Present Relations.” Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalology (1995), 6: 303-330, pdf-77785-13978-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Hartnett, Jeremy. “bars (taberna, popina, caupona, thermopolium).” Oxford Classical Dictionary (2017), published online, Bars (taberna, popina, caupona, thermopolium) | Oxford Classical Dictionary (oxfordre.com)

- Lagóstena Barrios, Lázaro Gabriel. “Sobre la elaboración del garum y otros productos piscícolas en las costas béticas.” (2007). lagostena-mainake.pdf (uca.es)

- Lev-Tov, Justin. “‘Upon what meat doth this our Caesar feed…?’ A Dietary Perspective on Hellenistic and Roman Influence in Palestine.” Zeichen aus Text und Stein: Studien auf dem Weg zu einer Archäologie des Neuen Testaments (2003): 420-426, Upon_what_meat_doth_this_our_Caesar_feed20160114-13618-1dw7gxy.pdf20160114-19908-1e47f64-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Morley, Neville. “Cities and Economic Development in the Roman Empire.” Oxford Studies on the Roman Economy: Settlement, Urbanization, and Population (2011): 143-160, 196.pdf.pdf (ethernet.edu.et)

- Nappo, Salvatore Ciro. “Urban Transformation at Pompeii in the late 3rd and early 2nd c. B.C.” Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series Number Twenty-Two: Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond (1997): 91-120, Urban_Transformation_at_Pompeii-libre.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

- Van der Veen, Marijke. “Food as embodied material culture: diversity and change in plant food consumption in Roman Britain.” Journal of Roman Archaeology (2008), 21: 83-109, Food-as-embodied-material-culture-Diversity-and-change-in-plant-food-consumption-in-Roman-Britain.pdf (researchgate.net)

- Vehling, Joseph Dommers. Apicius: Cooking and Dining in Imperial Rome. Project Gutenberg, 2009. The Project Gutenberg eBook of Apicius: Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome, by Joseph Dommers Vehling.

Living in the Longue Durée is part of the History Nerds Network, a group of friends who together make history content online. Check out our Discord server here if you’d like to chat with us: https://discord.gg/dzdrzUpKeG You can also follow for post updates on the Facebook page ( Facebook ) or on Instagram at @livinginthelongueduree .

Consider supporting my time and money investment into research on Patreon if you want to allow articles like this to maintain their quality and regularity: Living in the Longue Durée | A thoughtful and eclectic history blog. | Patreon

Leave a comment